In 2024, a group of Ukrainian artists, sculptors, architects, and researchers came together to develop ideas for one of Odesa’s key Soviet-era war memorials—the Alley of Glory. Grassroots elements of the Russian–Ukrainian War memorialization started appearing there back in 2022. But can the Alley of Glory be redefined completely?

The effort was a part of Memorialization Practices Lab, a learning and research project aiming to find a memorialization language for the Russian–Ukrainian War. It included a learning/discussion part focused on the approaches to working with collective memory and expeditions to memorialization sites that let the participants get an insight into the context and talk to the local community and authorities. Another part of the on-site activities was developing ideas for the participants’ memorial projects.

The memorial project ideas presented here are not yet ready for implementation since the Lab only aimed to develop the elements of memorialization language for the Russia–Ukraine War. Besides Odesa, the participants worked on cases for Kharkiv, Moshchun, and Chernihiv.

THE CASE

Odesa’s memorial landscape was shaped primarily by the memory of World War II. The Russian–Ukrainian War has rendered the innocuous use of Soviet commemoration language impossible and launched the rethinking of customary memoryscapes, informing the need to redefine Odesa’s central war memorial—the Alley of Glory in Shevchenko Park.

The stelae at the Alley’s entrance bear two dates—1941 and 1945, a vestige of the Soviet Great Patriotic War narrative. However, World War II began in 1939, and a memorial in present-day Ukraine must recognize that.

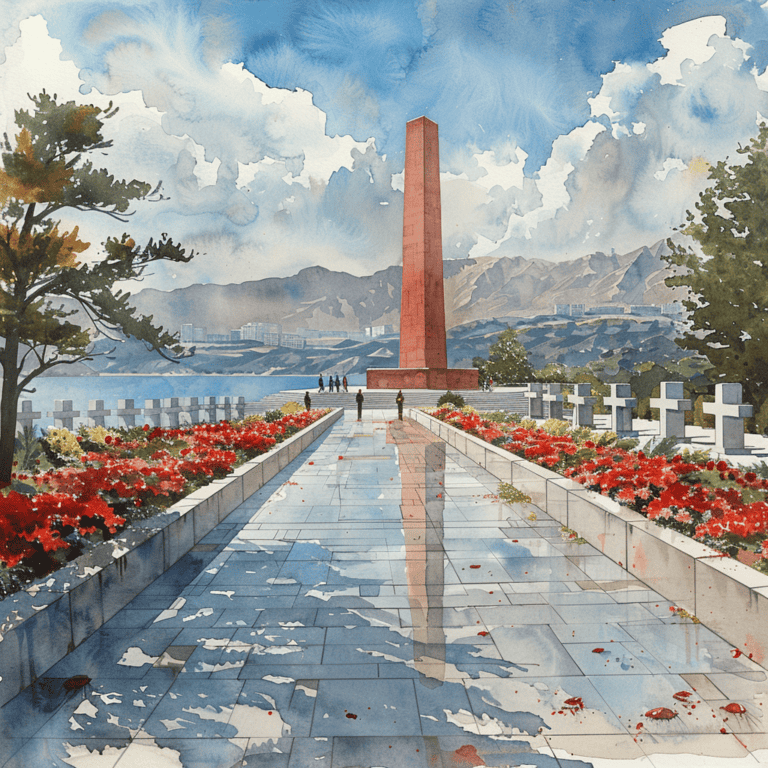

At the Alley’s end stands a Monument to an Unknown Sailor, inaugurated in 1960, a 21-metre-high red granite obelisk with an eternal flame at its base. On the obelisk’s four sides are reliefs depicting the events from Odesa’s war history: the city’s April 1854 defence during the Crimean War, the 1905 mutiny on battleship Potemkin, the January uprising of 1918, and the city’s 1941 defence. During Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one of the reliefs cracked during a Russian air strike on Odesa.

Photo by Natalia Dovbysh

Cenotaphs, graves of Soviet World War II heroes, and plaques with the names of Soviet heroic cities are lined up along the Alley. After Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, locals started redefining this part of the memorial, making it a site for grassroots memorialization initiatives. First, they covered with black plastic bags and eventually removed the plaques bearing the names of Russian cities. Later, a plaque reading “Heroic City of Kherson” was installed.

The Ukrainian laws “On the condemnation of the communist and national-socialist (Nazi) totalitarian regimes in Ukraine and the prohibition of propaganda of their symbols” and “On the Condemnation and Prohibition of Propaganda of Russian Imperial Policy in Ukraine and the Decolonization of Toponymy” stipulate that the burial places be moved from the city’s centre to the cemetery, and it remains to be seen what the rethinking of the burial site part of the memorial will look like. However, interring the Russian–Ukrainian War heroes in the Alley of Glory has already been brought up during the ongoing memorialization-related discussions in Odesa.

The history of the Soviet Alley of Glory’s creation highlights the contexts that shaped it. The memorial space at this site was established during World War II by the occupational Romanian authorities to commemorate the German and Romanian service members—their remains were later reburied in their respective countries. After World War II ended, Soviet authorities used this space to set up a memorial of their own.

The participants of the Memorialization Practices Lab went on an expedition to Odesa to study the memorial situation in the city before developing their proposals for a potential rethinking of the Alley of Glory.

CASE CURATOR

Oksana Dovgopolova

D.Sc. in Philosophy, Co-founder of the Past / Future / Art memory culture platform, member of the Memory Studies Association

AUTHORS

Maria Honchar

Media Artist, Architect

Natalia Lisova

Artist

Roman Mykhailov

Artist

Nelia Moroz

Architect

Dasha Podoltseva

Artist

Kateryna Pokora

Artist

PROJECTS

MARIA HONCHAR

Valour and Memory: A Modernized Alley of Glory Memorial

The project was born out of reflections on how eventful times of war are, suggesting the multilayered character of their memory. In April–June 2024, Maria Honchar googled the keywords discussed throughout the Lab’s duration, compiling a journal of AI-generated images and text descriptions.

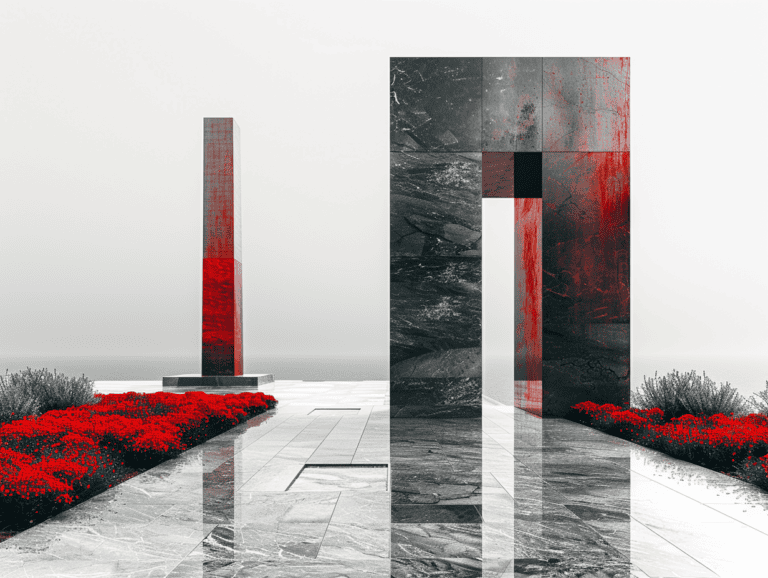

As she experiments with layers of imagery, the author proposes to reinterpret the symbolic meaning of the Alley by cladding the stela in weathering steel. The panels will naturally transform with time, becoming covered in rich patina and dust that impart character and depth to the structure. Another suggestion of hers is to change the memorial’s geometry from a pointed sword to a tower/castle. The project’s message is about transitioning from the Soviet heritage to the values of independent Ukraine without erasing the visuals of the past, and with it, Maria intends to assert the transparency of memory and the readiness to discuss all the challenges our country faces.

NATALIA LISOVA

Alley of Glory, Alley of Memory

Natalia Lisova’s project is rooted in the notion that Odesa ensures Ukraine’s marine safety and the understanding of the tragedy wrought on the city by the Russian invasion. For decades, the Alley of Glory embodied the memory of locals killed during the city’s defence in 1941 during World War II. However, it started losing its role as a symbol of unity over time, occasionally even sparking fierce debates.

The artist proposes to get rid of the Soviet symbols while retaining the representation of Odesa’s historical experience in defending from marine attacks since 1854, during the Crimean War, move all burial sites to the cemetery, rename the Alley of Glory to the Alley of Memory, and put a grey granite boulder in the stela’s place, with a stream of tears running down its surface and along the entire alley. Natalia believes the place may become a recreational site, “but contextually, the territory will retain the experience of war and Ukrainian resistance in Odesa”.

ROMAN MYKHAILOV

Caring For Past/Future

Roman Mykhailov suggests memorializing the care and puts his memorial’s message like this: “We remember our past, safeguard our future, and create our present”. As he reflects on respecting the past and values of the future that Ukraine is now fighting for, the artist asks himself: what kind of glory do we have in mind when we think about redefining the Alley of Glory in the context of the Russian–Ukrainian War? And then, he answers that question: Glory to Ukraine!

Roman suggests showing concern for the memorial and sheltering it. With scaffolding around the obelisk and two similarly shaped shelters on both sides, the memorial would resemble a trident, the symbol of independent Ukraine. “It’s just an art piece that cares for the memory of the past, which depends on our tending to the memory of the past. In fact, this piece is a monument to a monument. It protects a monument, but it doesn’t really exist”, the artist reflects.

DASHA PODOLTSEVA

The Wait

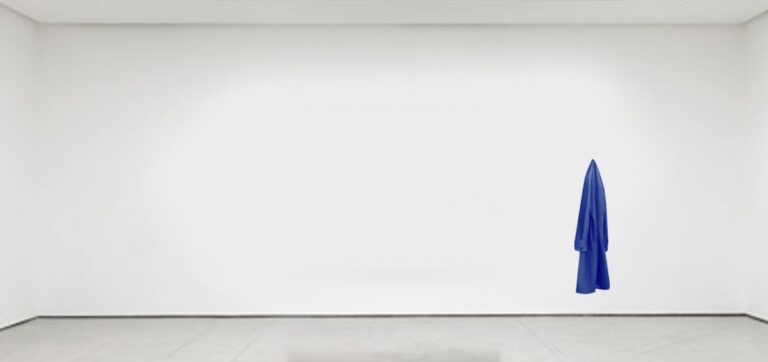

This project is all about the Ukrainians who perished or went missing during Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Dasha Podoltseva points out the dramatic difference between the Soviet memorial language and memorializing the Russian–Ukrainian War in the towering Soviet stela’s basic generalizing message—reducing the memory of specific people to that about “the many”.

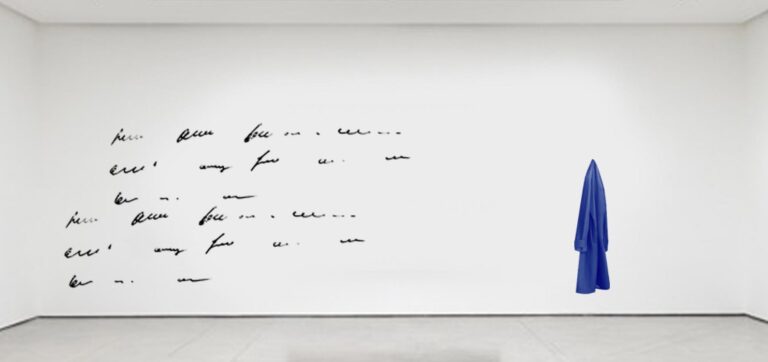

The artist envisions a temporary installation in the Alley of Glory of a coat hanging on an invisible hook, suspended in time as clothes usually are. It’s a coat that nobody’s coming to pick up already. With its shape resembling the central stela, the installation aims to highlight the human dimension of memory, both in scale and meaning, as well as personal pain as opposed to abstract heroism. The coat’s vibrant colour will contrast with the environment’s predominant palette, making it look as if taken out of context, feeling strange and out of place, like forgotten clothes.

It’s a temporary installation that can be exhibited within the space of the Alley of Glory to establish a visual dialogue with the stela or in a gallery. The artist also proposes to create a space where the visitors can leave their messages or pictures of those for whom they are waiting and whom they remember.

KATERYNA POKORA, NELIA MOROZ

Alley of Glory, Road of Oblivion

The authors reflect on the location’s complicated history and the relationship between memory and oblivion. As it exists now, the Alley of Glory references multiple war history events—from 1854 to the present-day Russian–Ukrainian War. Also, it bears witness to how Odesa residents’ values and views clash. The authors imagined a place devoid of ideological symbols transformed into a therapeutic space of serenity and contemplation.

Kateryna Pokora and Nelia Moroz propose to move the graves from the Alley of Glory to the cemetery, leaving only the Monument to the Unknown Sailor and the landmark obelisk. The space of the Alley would then become a living green field of steppe plants native to the Black Sea coast, with green memorial posts telling the story of burials here. A pocket of plants native to Romanian steppes may become a reminder of the Romanian military members once buried here.

The authors want to confine all ideological symbols to a museum space dedicated to World War II, which the premises of Station No. 1 can accommodate. Meanwhile, the Russian–Ukrainian War memorial can become a separate project, potentially spanning the entire hillside from the obelisk to the Red Packhouses and the sea.

MILESTONES

Mid-March–May 2024

The Lab’s learning section

April 2024

Selection of the participants for the Lab’s hands-on practice section

27–28 May 2024

Research expedition to Odesa

1 June–10 July 2024

Development of ideas, discussions with the curator, follow-up revision

20 July 2024

Presentation of project ideas

Expedition to the Russia–Ukraine War commemoration sites in Odesa, 27–28 May 2024

Photos by Natalia Dovbysh

ORGANIZERS

Past / Future / Art is a memory culture platform established by the Cultural Practices NGO in Odesa, Ukraine, in 2019. It focuses on memorial, research, and art projects and develops strategies for commemorating significant phenomena of Ukrainian history, initiating public discussions to engage broader audiences in working through the past.

Museum of Contemporary Art NGO (MOCA NGO) is a non-profit organization aimed at creating a new type of professional contemporary art museum institution in Ukraine, serving as a crucial element in the advancement of the art ecosystem. Founded in 2020, the organization brings together and engages artists, cultural workers, and experts who work with contemporary art in Ukraine.

The Memorialization Practices Lab is supported by the Partnership Fund for a Resilient Ukraine (PFRU), funded by aid from the governments of Canada, Estonia, Finland, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Fund unites the Government of Ukraine with its closest international government partners to deliver projects in primarily liberated and frontline communities that strengthen Ukraine’s resilience against Russia’s war of aggression. PFRU aims to strengthen the Ukrainian government’s capacity and resilience to deliver essential support to local communities in collaboration with civil society, media, and the private sector.