HACKING LENIN: THE FATE OF SOVIET MONUMENTS IN KAZAKHSTAN

As part of the public program of the project Past / Future / Art researcher, Kulshat Medeuova spoke at the online event “Avenues of Gods in the Country of Nomads: Post-Soviet Kazakhstan and Memory”. We published main points from the conversation.

LENINS: BIG AND SMALL

Kulshat Medeuova: We decided to talk about a particular type of Soviet monuments, called the “main monuments”. They are usually located on the country’s main square, in the capital, large regional cities, or even tiny villages. Most often, they are monuments to Lenin. At the same time, we mean that the theme of Lenin is a topic of a certain “surplus” of the Soviet.

In this photo, you see a rather comic situation. On the main square of Tselinograd (now the new capital of Kazakhstan — Astana, or Nur-Sultan) in 1970, on the eve of Lenin’s 100th anniversary, there were two Lenins together — the old and the new one. Precisely from this period, the radical restructuring of the commemorative landscape in the USSR began. The unification of monuments takes place; they become well recognisable, they become the monuments that we now presumably feel nostalgic about.

When we compare old Lenins and new, we see that large Lenins have always marked the late Soviet space. A specific paradox occurred: no one is looking for those first, “old” Lenins, but all conversations are about the fate of “new” ones. And when, in the 1990s, we chose the path of independence and began to think about our relationship with our Soviet past, we should understand, that this second, late Soviet wave of monuments was subjected to a major audit.

In Kazakhstan, the scenarios of displacement of monuments have unfolded in several versions. For example, in the city of Semey (Semipalatinsk), they were gathered on the nearest vacant lot between a medical school building and a dormitory. The monuments were in a chaotic setting for a while, but then an astonishing story happened: they were integrated into this place, and the city utility service providers cleaned up the location. The result was a small square, very convenient for walking along the embankment of the Irtysh River.

AN ASTONISHING STORY HAPPENED:

MONUMENTS WERE INTEGRATED INTO A NEW PLACE

During the redevelopment of this park, someone inscribed “gods” on fresh cement at the biggest monument, at the highest Lenin. As the project’s curators noted, the gods for your own culture, your territory, are always something else, something external. Soviet monuments in Kazakhstan are always an external instrument of influence, and displacing them on the urban periphery is a natural process.

On the other hand, not every city in Kazakhstan has such a Lenin park, and they are different. Differences are dictated by the peculiarity of the history of those cities. For example, Lenin park in the town of Kyzylorda is much smaller; it has long been inaccessible to its residents because it was in a small square on the closed territory of the railway administration. And this is also remarkable: talking about the capital of Kazakhstan (Kyzylorda had this status for some time) and asking why one or another city was chosen; we can answer: “Because there was a railway there”. So we realise that many of the monuments we have in Kazakhstan came from somewhere thanks to the railway or some other external possibilities. These are monuments that have not yet been produced on the territory of Kazakhstan.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, and the question of what to do with Soviet monuments arose, the authorities of the city of Atyrau paid no attention to their Lenin. But local historians insisted on preserving the monument. They installed it on a narrow street surrounded by five other small monuments and busts, including Chapayev, in a separate micro-district, “Zhylgorodok”. The history of “Zhilgorodok” has the same colonial history. In 1942 it was built for the new oil refinery employees; a special wall separated it from the rest of the city. As times changed, the other investors came into oil production and “Zhylgorodok” literally degraded as a city district together with its monuments.

Talk about Soviet monuments must begin with the understanding that within this group, there is a post-Soviet ranking: some still occupy dominant central places in urban spaces. For example, the monument of Kirov is ideally preserved in Ust-Kamenogorsk (eastern Kazakhstan). And the monument to Chapayev in Uralsk (western Kazakhstan) performs the role of a Soviet hero and a particular hero of the frontier. For residents, Cossacks, who also live in the area, Chapayev is a negative character. They would have no second thoughts about demolishing his monument — of course, yes! At the same time, Kazakhs say: “No, leave Chapayev, we like Chapayev!”. Such oppositions are formed by the local memory wars.

An interesting detail: in many cities, such Lenin parks are semi-abandoned, where Lenins simply stand in large or small groups. When you see a figure, you start to guess that it’s probably a pioneer, a hero or a nameless soldier. You can’t recognise them anymore. They are generalised, something like “The Girl with an Oar”.

The only city in which all monuments of the Soviet period had plaques with precise indication when this monument was built, where it stood, and when it was moved to Lenin park is Ust-Kamenogorsk. It’s a city whose natural physical body was built by heavy industry — the famous Atomoprom complex, which implemented the famous atomic project of the USSR. The identity of Ust-Kamenogorsk appeals to the belief in the power of Soviet science and the industrial potential of the city. Ust-Kamenogorsk has a very complex relationship with both its history and projections into the future.

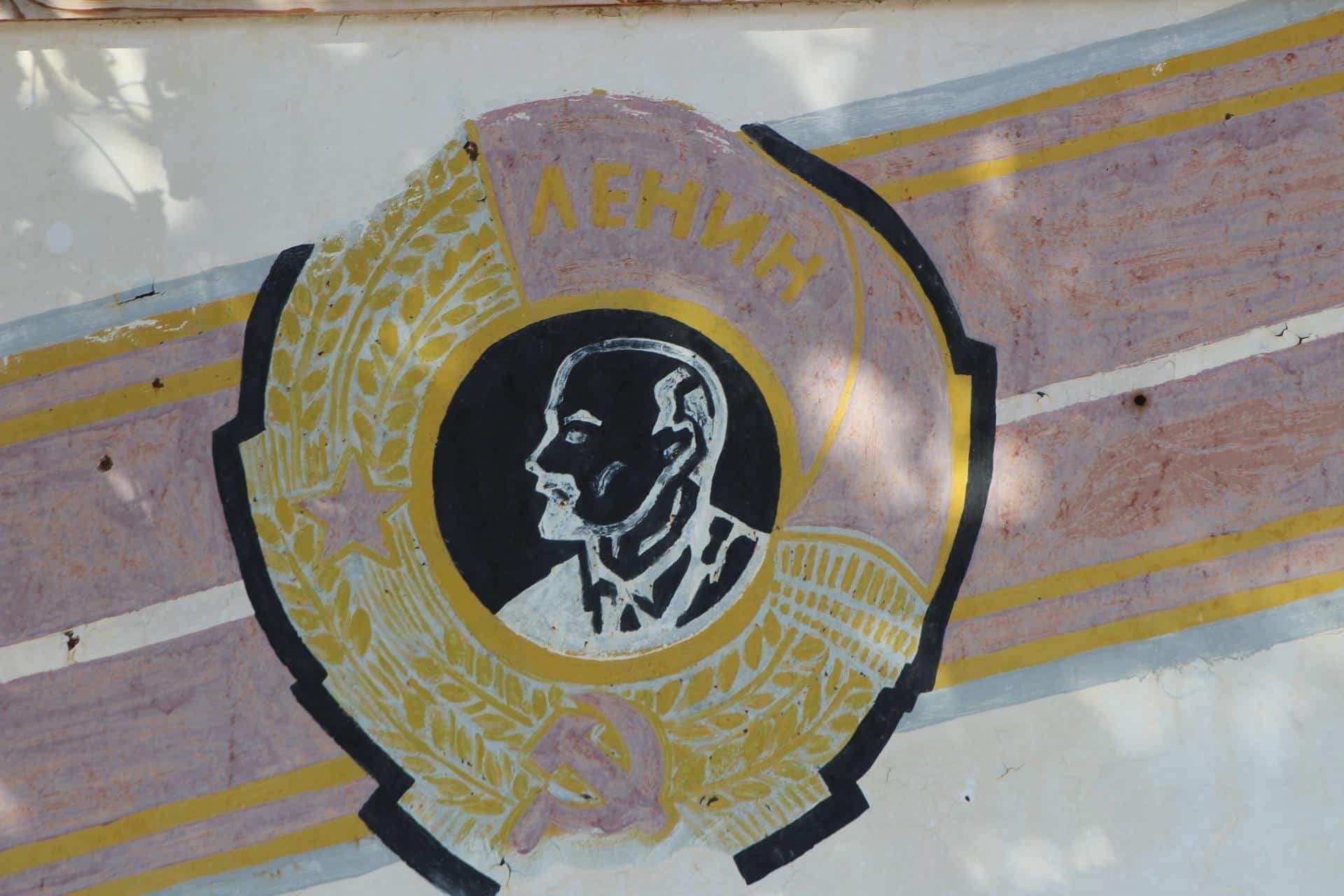

On one of the stands in the once-closed city of Priozyorsk, I found an image of Lenin. And it seemed to be a Banksy-style, “hacked” Lenin: it used to be white, now it was black. It is, of course, my speculation, as a visual anthropologist, I constantly encounter difficulties of interpretation, because a place itself cannot tell me how to interpret it. It cannot tell me: “We took all Soviet monuments to the outskirts of the city — look for them there”. In this interpretation, there is always room for imagination. The boundaries and volumes of this imagination are interesting themselves. When we are asked in Astana: “Where is your Lenin?” We say: “We’re not interested in it; we don’t need it. If you’re interested in it, look somewhere in the landfills. There is no Lenin park in Astana because there are too many other objects and activities to spend energy and resources on instead of searching for Soviet monuments”.

A NEW MEMORY FORMAT

Kulshat Medeuova: Kazakhstan made an almost global turn from the memory of the Great Patriotic War to the memory of the Second World War, and even more — to the memory of the Defenders of the Fatherland. Although every city still implements different algorithms of this recoding. Most often, the memory of the Great Patriotic War becomes part of another narrative, such as a global Kazakh understanding of the Fatherland.

The appearance in the Post-Soviet period of a new style of large monuments, “Defenders of the Fatherland”, is dictated not only by the blurring of the old “ideological matrix” but also by an active interest in the pre-Soviet history. Hence the new narrative which links not only World War II but also the Dzungar Wars. The concept of the defender of the Fatherland is being expanded, specified and recoded.

In the second variant, the Fatherland is beginning to be understood as all the tragic events of the 20th century in which Kazakhs participated. Such monuments can be called “Tagzym”, which means gratitude, bow. For example, in the city of Kyzylorda there was a Monument of Glory — a classic Soviet monument with eternal fire, symmetrical inscriptions that the heroic deed is not forgotten. Then, behind it in the alley, in the depth of the square, a new monument was created. It now complements the Soviet design of eternal пам’яті, memory, but differs in style.

Here there are several key blocs: the topic of trauma, collective participation in certain events: Afghanistan war, Chernobyl, the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site and Kazbat (peacekeeping military unit of Kazakhstan). This is a rare combination because we don’t see Kazbat’s monuments very often in Kazakhstan. Chernobyl monuments are everywhere. They are often combined with monuments associated with Afghanistan, and this is a new format of memory.

Oksana Dovgopolova: Afghanistan and Chernobyl are often neighbours in commemorative space. That has always surprised me. Why do you think they go in parallel?

Kulshat Medeuova: In the case of Kyzylorda, it is a question of where the monument will stand in the urban space. The Chernobyl community and the Afghan community alike insisted that based on the monument’s significance it could not be on the periphery, that is, that the memorials to these events should be near the Monument of Glory. In Uralsk, for example, these monuments are located in different parts of the city. In Astana, they are sort of nearby but not visually linked into one monument.

These groups are different memory actors; they participate in the lives of their cities in different ways and receive rights to their monuments. Similarly, locations of monuments may depend on the artist hired and how he promotes the idea in the city. The general policy is that monuments connected with the Second World War are now counted as monuments to “The Defenders of the Fatherland”.

Regarding the general configuration of traumatic memory, evident visual forms that describe what is associated with a large traumatic experiences are a torn shanyrak and a torn star. Shanyrak is a constructive element placed at the top of the yurt — the nomadic house in which the Kazakhs lived. It is considered one of the most sacred signs of material culture. And when it is represented as torn, it becomes a sign of traumatic experience.

THE SHORT HISTORY OF THE NORTH

Kulshat Medeuova: The rethinking of history is inseparably linked to the memorialisation of the former Gulag camps. Such places are very numerous and spread across Kazakhstan. Of the nearly two dozen locations associated with large camps, about five are memorialised in Kazakhstan. And one of those places of memorialisation is the museum in the village of Dolinka in a building that used to be the head office of the camps.

The question arises: how is Soviet heritage experienced and interpreted through art? Using the example of Askhat Akhmedyarov, one of the most famous contemporary Kazakh artists, I want to talk about a project that lasted three years. It was first presented in 2017 at the exhibition in the National Museum of the Republic of Kazakhstan called “Time and Astana: after the future”.

That exhibition of young artists, where Askhat was one of the curators, took place in the background of another major international exhibition “Expo” in Astana. During the project itself, and after, there was a lot of inspiring and solemn rhetoric. Everyone said that Astana was a great project, and how excellent everything was there.

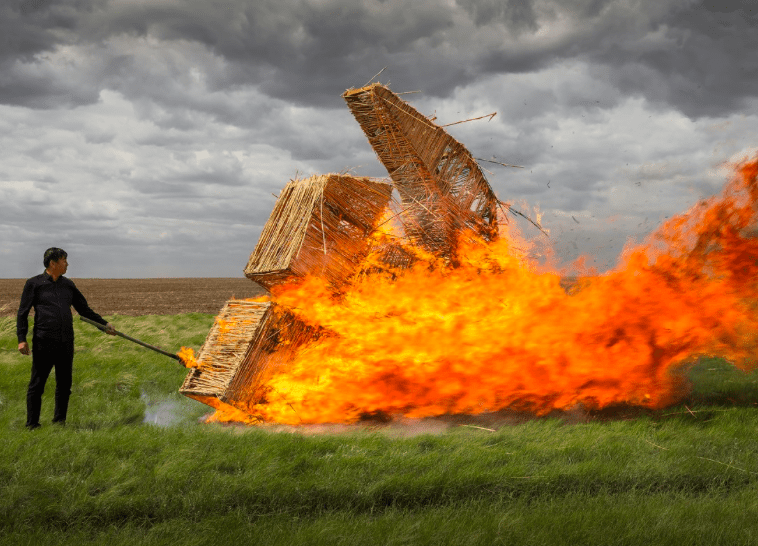

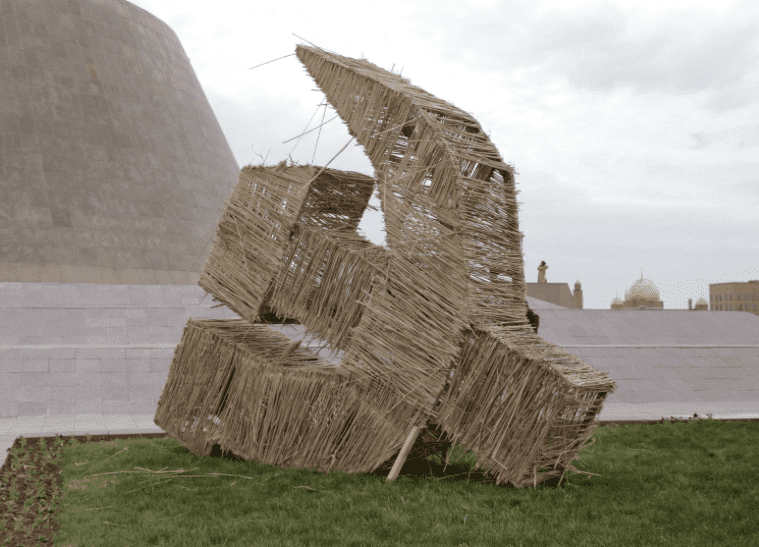

Askhat Akhmedyarov created the project “The Short History of the North” as a reference to what used to be in these territories earlier. These were Gulag camps. The closest one to the capital was the Akmolinsk Camp of Wives of Traitors of the Motherland, abbreviated as ALZhIR, and women’s labour was used to make mats out of reeds.

Askhat used this local material to make a hammer and sickle. Initially, it was an ironic expression: “Here you are talking about the Expo, about glass architecture, about the extraordinary possibilities of what Kazakhstan is going through now, but do you remember where everything started and with what tools and resources this city was built?”.

A year later, on May 31st, on the Memorial Day for Victims of Political Repression, he took the same reed structure to the ALZhIR Museum. The composition stayed there for a while. There were other exciting objects in the museum: big cubes filled with soil. The soil, in this case, mattered — it was from “Mamochkino” Cemetery (translates as ‘Mummy’s cemetery from Russian — note by Past / Future / Art) — from other places of traumatic memory in Kazakhstan. There is also a giant cube — a memorial sign to Ukrainians who died in the camp. There are many such cubes for almost every nationality.

Back to Askhat Akhmedyarov’s project. From ALZhIR, he took the structure out of the settlement to fulfil his plan — to perform an almost shamanic ritual using this Soviet symbol. He called this part of the project “If the pain could burn”. He set fire to the hammer and sickle. As Askhat himself wrote about this part of the project, this was an important act: it was vital for him to deal with this external thing and perform a kind of purification procedure, like shamanic practice.

HE BURNT THE HAMMER AND SICKLE BECAUSE IT WAS IMPORTANT TO PERFORM A PURIFICATION PROCEDURE SIMILAR TO A SHAMANIC PRACTICE

Oksana Dovgopolova: I will take this opportunity to say thank you to Askhat Akhmedyarov for the support he demonstrated to Ukraine when Crimea was occupied. His solo protest at the Embassy of Ukraine was critical to us. He must know about it.

And our subscribers see parallels between Ukraine and Kazakhstan: “New Lenin is desacralised and small” for both countries. Maybe that’s why it is not scary anymore — the desacralised figure becomes a figure of the past that no longer threatens us; it no longer organises our space; it is a trace of what has gone.

Kulshat Medeuova: Where do we still have Lenins? In places where there was no economic growth. He stayed in many large villages. If there were no economic upgrades, you will meet Lenin. All Soviet infrastructure will be destroyed there, but Lenin will remain. But in those places where there has been economic growth — oil-related or otherwise — monuments have definitely changed.