FINLAND AND UKRAINE: TWO CENTURIES, TWO WARS

Modern Ukrainian artists turn their practice to the topic of the Russo-Finnish War; to the events that happened more than 80 years ago. Why do they care about it now, and how can this help understand the current situation in Ukraine?

It may seem strange that in recent years Ukrainian artists turned to the Russo-Finnish War or the Winter War of 1939-1940. The Soviet Union then provoked an armed conflict in Finland and annexed a part of Karelia along its border areas. During the Soviet period, these events were deliberately censored and, after the war, remained outside of the public sphere little known to the general public in Ukraine.

The current situation in Ukraine, Russian aggression and war in the East makes artists look at the experience of occupation and forced displacement that has happened to others. What are Ukrainian artists asking about looking at the events of this distant and ostensibly not-very-close-to-Ukraine war? How are the images of winter events in Finland at the beginning of World War II reflected in the thoughts of contemporary Ukrainians? These issues are the focus of two projects that have been created in recent years.

ANDRII DOSTLIEV, LIA DOSTLIEVA, OLGA ZELENSKA

LOST KARELIAN LANDSCAPES, 2019—2020

Andrii Dostliev and Lia Dostlieva explored the photo albums of Finnish families who had to evacuate their homes in a hurry in 1939. They left everything and could only take the essentials with them. Some were lucky enough to return after the temporary retreat of Soviet soldiers, but only to escape again — this time for good.

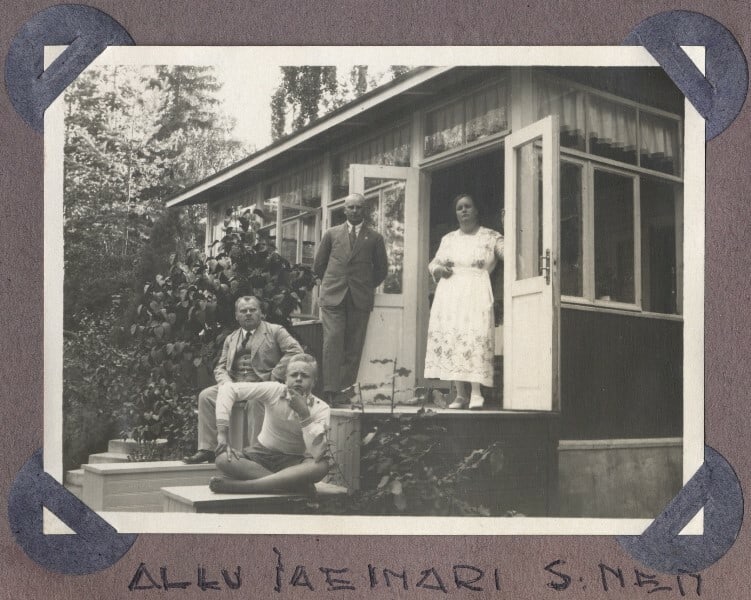

In family photos of Finns taken before and after the war, the house occupies a special place. Artists point out how the style of the images changes. In the photos before the occupation, there is a lot of space and light, people, and things that can be called one’s own. In the pictures after the displacement, the poses are uptight and forced, compositions are poor and the feeling that everything is “foreign” is present in the photos.

The Siltasen family on the porch of their Samol villa, 1920

from the collection of the Viipuri Museum in Lappeenranta

photo — www.korydor.in.ua

Lancinen family in Kuhmalahti, Pirkanmaa, 1940

from the Lappeenranta Museum

photo — www.korydor.in.ua

“For thousands of Karelian evacuees, previously mundane amateur photos of their own houses became, effectively, the only visual link with the lost homeland”, Lia Dostlieva and Andrii Dosltliev write about their research. “Something which used to take a secondary place in the family album acquired new meanings and new weight. These photos were reproduced, re-drawn; some people would even order big coloured pictures to be painted after a small faded black-and-white picture. Now and then, these paintings still decorate the houses of the second generation of evacuees and, despite the occasional colouristic discrepancies, still function as a link with the land of their parents”.

photo — www.korydor.in.ua

As a continuation of their research, the artists created the project «Lost Karelian Landscapes» in collaboration with the designer Olga Zelenska. They started with re-drawing Karelian houses from pre-war amateur photos onto hand-made paper mixed with seeds of plants widespread in Finland. When these seeds began growing, they documented their growth in the landscape. Then they violently interrupted this growth and dried the pictures for a makeshift herbarium, an album of memory landscapes.

Lost Karelian landscapes, 2019–2020

series of photographs documenting long-term performance, drawings, dried plants

photo — www.korydor.in.ua

ALEVTINA KAKHIDZE

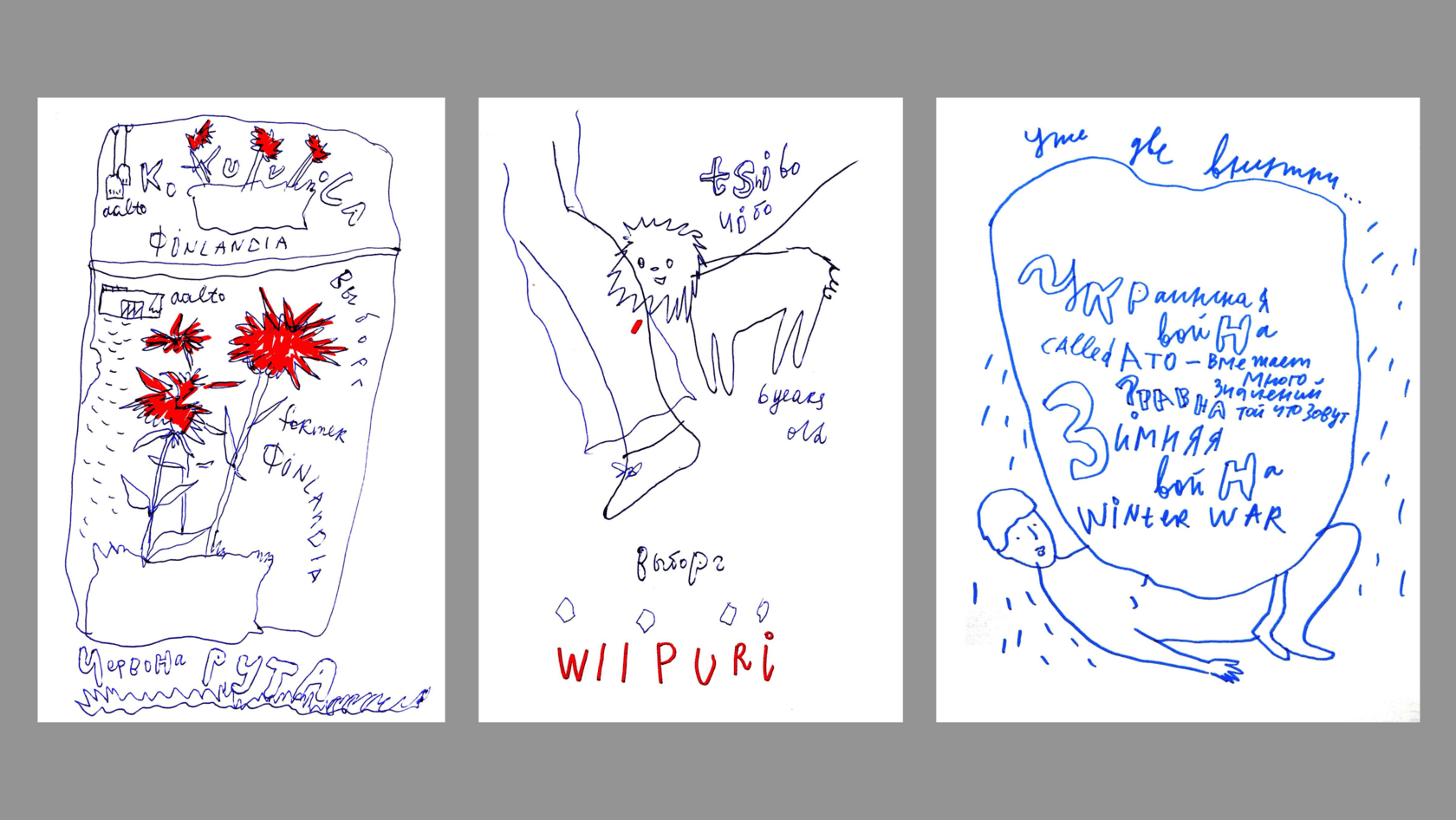

WINTER WAR: AN ARTISTIC INVESTIGATION, 2015

In 2015, artist Alevtina Kakhidze went to Vyborg, a Russian city in Leningrad Oblast, 27 kilometres away from the Finnish border, called Viipuri before the annexation.

The choice of the people to stay in the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions after 2014, was an important topic for the artist. She asked herself, whether during the Russo-Finnish War there were people who decided to stay in a foreign country? How did they survive the occupation? The artist asked herself if any of the 450,000 Finns, who had been forced to evacuate due to the Sovietattack, wanted to stay on their land? She decided to find these people on her own.

www.facebook.com/alevtina.kakhidze

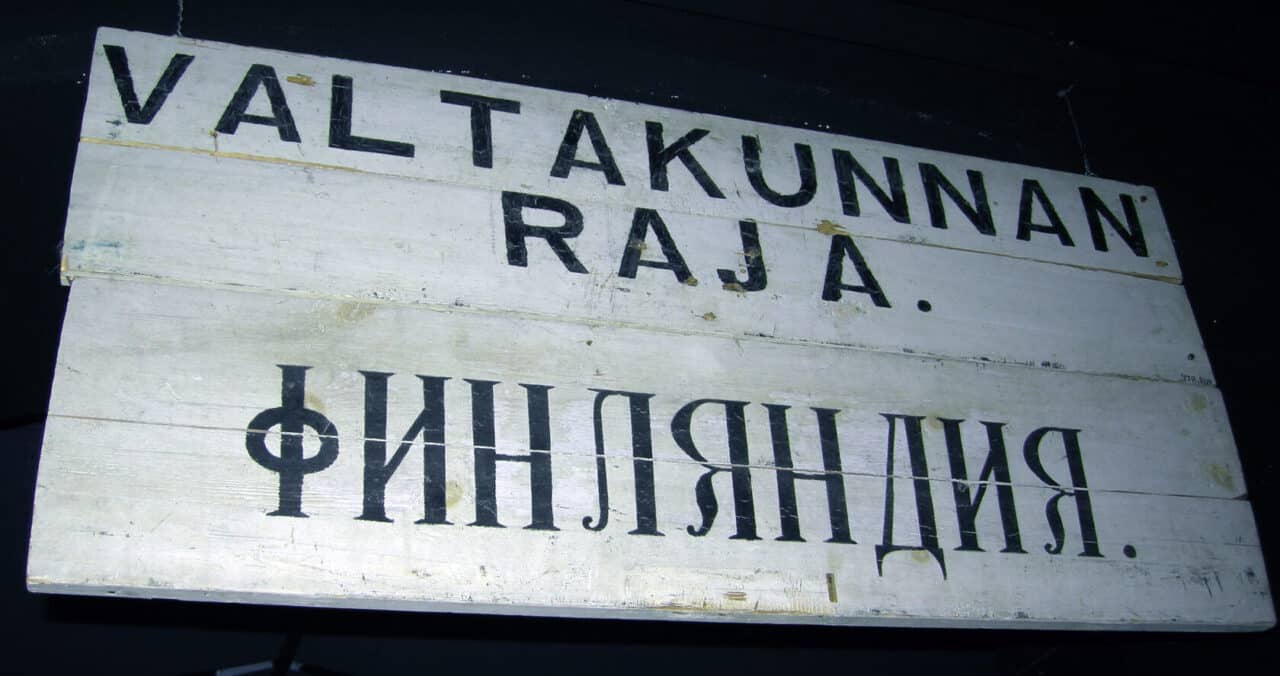

Jumping ahead, we can say that Alevtina Kakhidze did not meet the native Finns in Vyborg. However, she met many interesting people and even one four-legged descendant of immigrants. She also learned what is the most significant place in the city. It is a library designed by the world-famous Finnish architect Alvar Aalto in 1927–1935. And why the original curtain with the sperm image designed by the architect as a joke was taken off.

photo from the archive of the Central City Alvar Aalto Library, Vyborg

On this journey, it was not the formal result that mattered but the actual artistic investigation and the reflection it caused. In a conversation with a Finnish historian, the artist says: “In Vyborg, I was bitten by a dog. It hurt. It was a descendant of the Finnish dogs of those places. I forgive his instincts. To consider this land as one’s own means to protect it”.

We invite you to read the results of the artist’s research and to spend some time with her on this journey. And also to make your conclusions about the parallels between the two wars.

Title photo — Winter War Museum, Finland

provided by Alevtina Kakhidze