“THE ENTIRE TERRITORY OF UKRAINE IS A MUSEUM”: A CONVERSATION ABOUT SOVIET MONUMENTS

We publish the second part of the conversation “Soviet, empty, yellow-blue” with the documentary photographer Yevgen Nikiforov, which took place within the public program of the project Past / Future / Art.You can read and watch the first part — about the photo series “On Republic’s Monuments” — by following this link.

Oksana: Yevgen presented to us his artistic study of changes in public space in the context of decommunisation processes. In my opinion, this material is very valuable in terms of the constant involvement of the author in observation, in the context, and not only through the fixation of the environment but also by talking to people.

When we were preparing for this conversation, we discussed what artistic research is and looked for texts about its nature. And it seemed to us that this kind of research in publications is described as something fake. As if an artist tries to elevate his status by using terminology from a different field. But I’m certain we’re seeing an independent phenomenon here. So, Yevgen, what is artistic research for you?

Yevgen: It’s a chance to get to know the subject better. Through constant travelling and working with the material, I understand better what public space means and what it is. And I try to break down some stereotypes for myself about a particular region, about what monumental propaganda is, whether it works now. Finally, it’s a way of getting to know the place where I live.

It seems to me that thanks to this long-standing relationship with the public space, we can do some truly honest research. I don’t have an academic background, but I can work in other ways. I’ve shown 150 slides, but there are thousands more — from this array, we can extract the main and the most valuable photos.

Kateryna: What you’re talking about is two different ways of working with different results and different methods. And that doesn’t mean that academic is good and artistic is bad.

Oksana: It is one of the goals of our project, and of this meeting especially to try to answer the question of what artistic research is. Because an artist doesn’t have to do an academic job, there are academic researchers who have their methodology. However, artistic research gives an entirely different result and an opportunity to ask questions in a specific way. And perhaps this experience, which the artist acquires and shares with his viewer, involving him in the process of learning itself, is the most valuable.

There are criteria for scientific knowledge that Karl Popper once described: scientific knowledge must be one that can be verified and disproved. Observations and information gathering are the preliminary stages. The nature of artistic research is different, and here the process of the artist’s relationship with the subject matter is essential.

Artistic research provides an opportunity to work on a metaphorical level, observing the real world. Scientific research can’t afford that. Working with subjective experience in academic science requires many additional methodological tools that enable a move to an objective level. And science has a definition for non-scientific knowledge — it’s also knowledge, but different in nature.

If we look at artistic research through the optics of academic science, then it is thus non-scientific knowledge. Therefore the use of the concept of research is allegedly impossible here. But artistic research is a particular type of search that simply does not need to be compared to an academic one from a hierarchical point of view.

THE SECRET LIFE OF MONUMENTS

Kulshat Medeuova, a researcher of the memorial landscape of Kazakhstan, joins the discussion. Read the conversation with her: “Hacking Lenin: The Fate of Soviet Monuments in Kazakhstan”.

Kulshat: Yevgen’s lecture, his visual narrative led me to several conclusions and two questions. First, the role of utility service providers and their impact on our commemorative landscape cannot be underestimated. Memory has many agents, and not all of those who create memory discourses are top-notch professionals, art critics, or researchers, they can be simply interested people. A researcher should be attentive to such nuances.

The question is about the paint, its quality, the particular texture. For example, were there special requirements for the colour used by the utility service providers to paint the objects and the public space itself in yellow and blue? Were there any requirements for a specific texture of the paint or maybe it had to necessarily be produced in Ukraine? Or was it important that it was simply of good quality?

Yevgen: Unfortunately, I am not familiar with the paint brands used by Kyiv and other Ukrainian utility companies, but they have something in common — in a year, the paint fades, and in five years, nothing remains of it. You have to repeat the procedure. And what emerges through the fading paint is what was underneath it originally, and we get a mixture of two images, sometimes even three. As thousands of objects have been repainted, by now thousands of objects have almost regained their original appearance.

Kulshat: Another issue concerns the secret life of monuments. It turns out that when the taboo was broken — a kind of a rule for keeping distance, when people do nothing but bring flowers to the monuments — and when suddenly they were allowed to do anything with the monuments, like touch-up their feet, put on scarves, saw them, these monuments began to look different. While they were standing uninjured, they did not trigger any special feelings, but when they were all “injured”, they suddenly began to cause nostalgia. Especially when the monuments were “gone” or taken away to some private companies. Can you tell why people love them so much? For their Sovietness or for the fact that these objects attract attention themselves?

Yevgen: Everyone has their own reasons. Speaking of the “glass-cutter” (Vladimir Linyvy’s private museum of monuments and busts in Kharkiv — note by Past / Future / Art), he collects not only monuments but also boxes and all kinds of stamps. It’s a collector’s job for him. And for some, it’s preserving the ideological message and the memory that is valuable to this particular individual and keeping as much material as possible. So here are two basic approaches — the collector’s approach and the person who tries to preserve memory.

THERE IS STILL NO MUSEUM OF TOTALITARIAN PROPAGANDA, SO THESE COLLECTORS HAVE NO HOPE. THERE’S ONLY ONE HONEST WAY TO KEEP WHAT MATTERS TO THEM

Kateryna: During your work, have you noticed topics for artistic research that no one is working on today, but which would be good to explore in modern Ukraine?

Yevgen: In fact, there are so many of them, and the more I travel around the country, the more of them appear. They tend to follow from one another. Now I’m interested in the topics of the experimental-exemplary village, and rural labour. This project had already been shown in part at the Biennale of Young Art in Kharkiv in 2019. The short film “Kettlebells Oh My Kettlebells” for the festival “86” was made about it, but for me, it is a story that stretches ahead for several years.

I am also concerned about what happened this year — both the lockdown and the fires in the Zhytomyr and Luhansk regions. I decided not to work on this topic, so as not to chase the moment. I will wait and look at the long-term consequences. I’m also interested in the topic of water life, water pollution, pollution in general. I’m still working on some ideas, but that’s in the future.

Kateryna: Watching and listening to your presentation makes it look like you’re travelling on your own. Is artistic research a purely individual practice, or is there a need at some point for a team, for institutions, for support? How is everything organised?

Yevgen: Of course, there is always a need for support, often financial. But research is done in-house, so to say. I talked to the locals and asked about a monument or something I wouldn’t learn from a book, for example about very small monuments. I also worked in the library, starting with something massive — books about monumental art, monuments of Soviet Ukraine — and jumped from them to look for authors that I was interested in or objects that might disappear.

I have perhaps not yet reached the point where this archive will be helpful for other researchers, and I do not know what to do with it. So far, it all works as an artistic work, as this project has been exhibited approximately ten times in different European and Ukrainian institutions. And while it’s at work, I can’t say I’m done.

If we ever have a museum of totalitarianism, a museum of monumental propaganda or something, maybe they will need these photos for studies. For example, there are my photos in the Ludwig Museum in Budapest; they bought a series of works to add to their collection. In Ukraine, they only exist in private collections, but none of the institutions contacted me.

DECOMMUNISATION, MARCEL DUCHAMP AND THE PARK OF THE PAST

Kateryna: We have questions from the audience; let’s hear them.

Artem Grechka: Is it possible to look at a mosaic or a monument through the eyes of a spectator, not a photographer, after thousands of photos have been taken?

Yevgen: That’s my approach. On the one hand, it’s an art object for me, and on the other, it’s an artefact, like I’m in a museum. The entire territory of Ukraine is a museum in which these monumental works are built. And for me, it’s an artefact of a different culture, but it’s closely related to where I live.

Alevtina Kakhidze: Are you for decommunisation or not?

Yevgen: I’m all for desovietisation. For moving away from Soviet ways of working with everything in the world. I’m also for decommunisation. I think it should have started 30 years earlier and been more civilised. And what’s left of it needs some kind of moratorium — we have to work with it, rethink it.

Svitlana Boltovska: What’s next with the statues? It would be wise to take them to a place like near Budapest and make a park of the past. Near Budapest, there is a surreal spectacle when Soviet monuments gain new meaning. Or in Berlin, the head of Lenin was blown off, buried, then dug up, and now this head lies on the side in the exhibition “Destroyed monuments of 18-20 centuries” in Spandau.

Yevgen: I am very “for” creating such museums, as it is through these objects you can best get acquainted with the epoch. For me, the biggest shock of my life was visiting the Auschwitz museum in Poland. I don’t believe that anyone would want to repeat it after seeing this place.

THIS IS MATERIAL EVIDENCE OF WHAT CRIMES HAVE BEEN COMMITTED, AND THIS IS THE BEST LESSON NOT TO LET IT HAPPEN AGAIN

Also, I think these monuments should be preserved in one place with signatures, explanations, so as not to forget and feel this monumentalism and some fear — the whole gamut of feelings that can only be felt when you are near a material object.

Taras Grytsiuk: Do you consider Soviet monuments to be markers of Ukraine’s colonial dependence on the Soviet Union? Or perhaps it is not so much about colonial dependence as it is about active participation in the life of the Soviet empire? By demolishing these monuments, we are in a kind of denial of our role in what the Union was.

Yevgen: I have another view. I don’t feel these monuments are ideologically staining me or the public space I live in. They can’t change my thoughts about what happened in the 20th century on the territory of Ukraine, about crimes. But I also realise that not everyone has that kind of view, and many of these monuments still act like a red rag.

On the one hand, according to recent studies, in Ukraine, about 30% of the people support decommunisation, about 30% of the people don’t support decommunisation, and the other half are undecided. So it’s a subject of debate where dialogue is required. And you need a place where you can talk. Perhaps a museum will become such a place because other methods didn’t work out, as I think, the differences have not diminished.

Is there a tinge of colonisation in it? It’s hard for me to say. But you have to work with what you have. Most of the monuments are gone. And it may no longer make sense to talk about decommunisation because there is no subject to talk about — there are hardly any monuments left in public space.

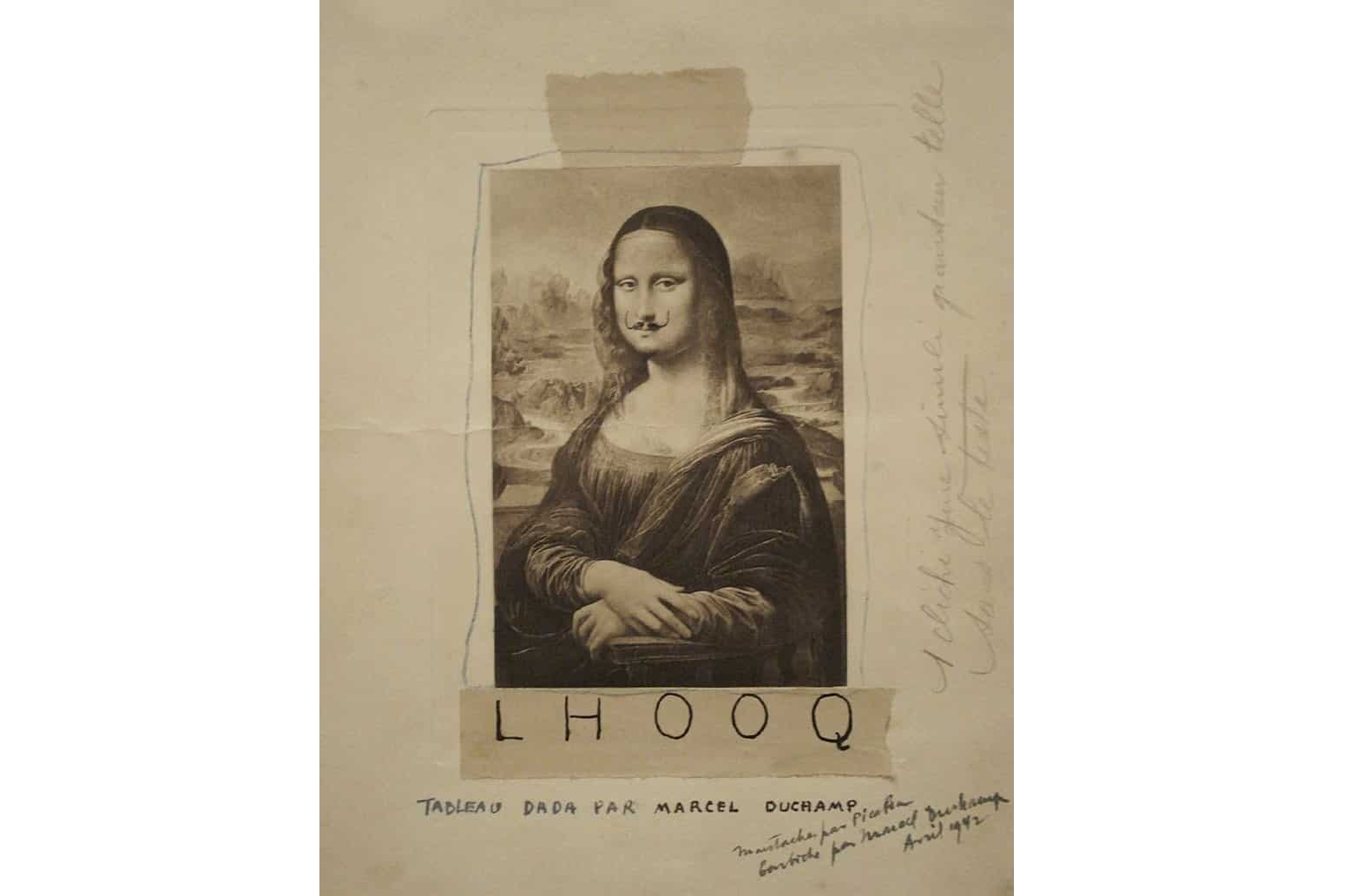

Alevtina Kakhidzе: What do you think is common between the monuments of Lenin in 2014 and today and the work of Marcel Duchamp, in which he painted a moustache and a goatee to the reproduction of “Mona Lisa”?

Oksana: Duchamp launched an iconoclastic series of Gioconda portraits with a moustache as a gesture for the situation in which a work of art is copied and turned into a sign without content. “Sacred” image is destroyed and is changed from sacred dimension into ironic. Strangely, such a radical decline makes it necessary to stop and answer the question of the actual artistic value of the images, erased by copying.

Duchamp said: “It’s a man!” highlighting the symbol of womanhood. I would say that Lenin’s colouring in yellow-blue has a slightly different nature. It is not about asking about the nature of a work of art but about the “disarming” of an ideological message. If Duchamp made me ask: “What exactly do I see?” Then painted Lenin sends a signal: there is no danger here. Duchamp has a provocation, here we domesticate.

Kirill Lipatov: After the war, the sculptures of Arno Breker were buried in the Berlin parks. Seventy years later, it was excavated and exhibited in Schwerin. Could the thesaurisation (hoarding; creating the country’s gold reserve — note by Past / Future / Art) of Soviet agitational art save itself?

Yevgen: Of course it could, because the number of monuments is enormous right now. If we dig up now what was hidden a hundred years ago or back in the 1950s, then in a few years, I’m sure we can find what was hidden now and evaluate it in a new way.

Ancient Rome had a memory curse when material objects in memory of the ruler were erased. Similarly, I think, in 2,000 years, people will look at these objects differently. They will be much more valuable than they were at the time of their creation.