NEVER AGAIN, OR WE CAN REPEAT IT?

As part of the public program of the Past / Future / Art project, curator Oksana Dovgopolova met with the director of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance Anton Drobovych to talk about the most important symbolic event of the 20th century — Victory Day over Nazism, and how the memory of the war is reflected in modern Ukrainian society. Read the key thoughts of speakers below.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

The victory over Nazism was the starting point of the project of modern Europe built on the idea of the value of human life and dignity. After the Second World War, it became clear that any ideology based on superhuman values — race, party, etc. — could lead to catastrophe. The concept of a crime against humanity was formulated, and subsequently, conventions on the crime of genocide were adopted. This is a crucial layer of meaning that must be kept in mind when we speak about the causes of the events of May 1945.

It was a victory of several states, which through mistakes and mistrust, came to the idea of uniting efforts to overcome Nazism. A community based on human rights, the need to protect a minority, the need for international efforts to confront the absolute form of evil — all have become common ground in the post-war world.

Oksana: Many countries have been involved in the common victory gesture, including Germany, despite the difficulties of overcoming its past. It is a glance to the future and understanding that only our daily efforts can turn that future into reality.

But involvement in the victory over Nazism can be felt in a completely different way — as a vision of one’s exceptional nature (“allies are not important”), heroism, for which the whole world should be thankful. The victory in this case is the starting point for an identity, constructed as a glorification of war: sacrificial heroism and a desire to repeat that feat. The past cannot finish — it is constantly present here and now, and the present can be annoying by not resembling the heroic past.

These are two very different value models. Human rights, calling a crime a crime, looking to the future — and the winner’s mission, the cult of heroic death, and the “we can repeat it” attitude.

Anton: The official discourse of memory reflects the values of the state. Part of the work of state bodies with collective memory always entails a forming influence. If it is moderate and built on liberal optics, it is one thing — a frank conversation when society says: “Let’s talk about it”. And there are repressive models, as in Russia now, when no one talks to people but simply gives the “correct” answer. Official memory turns to agitation, as in Soviet times — it is actually inertia from the Soviet time.

What do we have with the two models of commemoration, with the slogans “We Can Repeat It” and “Never Again”? “Never Again” is about reflection. We read Anatoly Kuznetsov’s “Babi Yar” and find stories about how the child lived through the occupation. It seems like a book about the war, but as a reader one knows very well that it’s about the difficult family life, his grandparents, his mom, his cat. When one is immersed in the world of personal feelings, one thinks: “God forbid such a thing”.

But there is a second slogan — “We Can Repeat It”. All this exaltation when on trolleybuses it is written: “To Berlin!” When we are told that our rockets can turn anything into radioactive ash, that we’ve won the war on our own — we face a model that appeals to the heroic spirit of the war, makes it attractive. It seems that war is the normal way to solve problems, so real human suffering falls out of this matrix. And that’s the danger.

I will go on a little historical detour to figure out the roots of these two models of commemoration. The slogan “Never Again” begins with the anti-war speech of Pope Benedict XV, which he made after the First World War when all horrors were still fresh: trench warfare, disease, typhus. He said, “Never again war, war never again!”

“We Can Repeat It” starts with an inscription on the Reichstag in Berlin,1945: “For air raids on Moscow, for the shelling of Leningrad, for Tikhvin and Stalingrad. Remember and never forget. Otherwise, we can repeat it”.

One Red Army soldier just came there and made an inscription on the wall: “We can repeat it!”. So this matrix suggests that it’s fair that we were attacked, fought back, and left. But no recalls that whoever defeated the aggressors then stayed and occupied European countries.

This historical frame intertwines with the models of commemoration: on the one hand, it is the heroism of war; on the other, it is pathos. We are in danger because such a bravado-like memory is easy to manipulate: it is exalted, causes false pride, but for whom? A pride for those people who would have never speculated on this topic because they remember what this war was, and they don’t want to repeat it.

TWO DAYS, TWO DATES

Oksana: We announced a meeting dedicated to two dates — the 8th and 9th of May. The first is a Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation. The second is Victory Day.

I would like to remind you that in the experience of the Soviet people, there was a situation of celebration of May 8 and 9 as memorial days and days offs. This practice began in 1965 and was part of Brezhnev’s formation of the victory paradigm. Two days also had two different emphases — May 8 was declared a holiday with reference to the feat of the Soviet women. It was first mentioned in Brezhnev’s report on Victory Day in 1965. When we hear “it was never touched, and now you want to add something alien”, it is not quite true. From 1948 till 1964, Victory Day was not a holiday at all.

The Day of Remembrance and Reconciliation appeared in Ukraine in 2015 as an addition from another commemoration paradigm, giving people an opportunity to see connotations unusual in our public space. But very quickly, the extra day became the source of the conflict. Why?

Anton: The answer, I assume, is Russian aggression and war. It always disturbs society, aggravates the sense of justice. We have such a story: those who are”for” May 8 are such good Europeans — it is a new, post-revolutionary trend. And all those who are “for” May 9 are for the old — there is the temptation to say it. And the war has added emotion here.

We shouldn’t say: “this is bad, and this is good”, instead we should say: “we have different cultural memories, let’s learn about their interdependence to understand why people advocate different things”. You can’t cheat. We have to put all the cards on the table and say, “This is such a complicated reality; these are the practices”.

If a person says “Great Patriotic War”, “World War II”, “German-Soviet War”, — we have to find out what he or she means, why he or she is using a particular concept. Is this part of an ideological position or is it simply easier for a person to use one another term.

THE SYSTEM “FRIEND-FOE” IS VERY DANGEROUS; YOU CANNOT START THE SEPARATION THROUGH THE USE OF WORDS. IN OUR COUNTRY, WE ARE ALL FRIENDS.

The Democratic Initiatives Foundation published a study that showed that most people in Ukraine are ready to celebrate both the 8th and 9th of May. The majority of the Ukrainian society is prepared to admit that Nazis and Communists were equally involved in the outbreak of the war. But on the other hand, the double celebrations of the 8th and 9th are the European and Soviet models together.

We realise that millions of Ukrainians died in the struggle against the Germans. But we also understand that this war was brutal, terrible, that the Red Army commanders themselves were very different about people and sent thousands of people to certain death. That is why a purely European model is not appropriate for us, our victims fall outside of it.

The official motto “We remember. We win” reflects this complexity. It is a compromise: on the one hand, there is the victory and millions of people who share it, on the other — memory shared by other people.

DAY ONE. RECONCILIATION

Oksana: I think Day of Reconciliation is precisely about reconciling our society. It’s about today, about how we talk about the past. And we recognise that even within our society, there were people on opposite sides of the barricades. But now, we are creating a shared vision of the future.

Memories cannot be reconciled. Society reconciles itself by analysing the past and calling crimes crimes and victories victories. So long as we do not speak about our history’s “black pages”, society cannot reconcile because everyone has their own grudges. Reconciliation is not only about reconciliation between enemies but also about reconciliation within society — children, grandchildren and all who remember.

Anton: It is hard to work with reconciliation — we remember that people fought in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, in the Red Army, in the Wehrmacht. Part of Ukrainian society hated communists, and part of it was in solidarity with them and lived peacefully. And yet another part of it were heavy-handed Communists who reported to the KGB and killed their fellow citizens.

Reconciliation means the beginning of such a discussion, bringing citizens’ attention to each other and the past to such a level where both the murderer and his heirs, the one who lived well and the one who fought against the communist regime, at least a little bit recognised the fairness of responsibility and agreed: “Okay, this is what we share, we cannot agree on the past, but at least let us define a model that will allow us to live together and not hate each other in the future”.

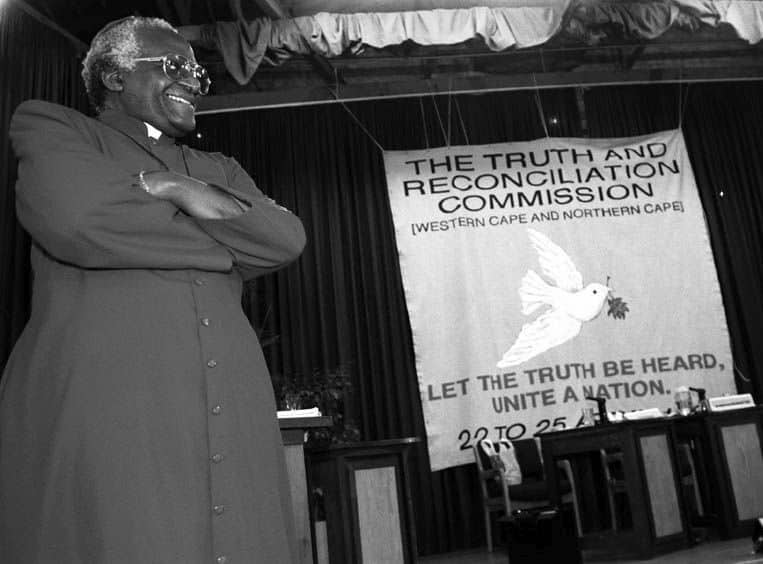

Oksana: I would like to clarify the matter of reconciliation. It does not mean forgiving criminals and letting go. The Day of Reconciliation is often accused of that. I would cite an example from the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which invented the following formula: people who committed the crimes of apartheid could be exempted from punishment if they provided full details of what they have done. Why was that necessary? Because it was the only way to get information and restore dignity to people who were tortured and killed.

There was an episode where a relative of one of the deceased asked about the murderer: “What, I must forgive him?”. Desmond Tutu, head of the Сommission, replied: “You don’t have to forgive him”. There are things we can’t forgive, but their articulation, revealing the truth about what had happened, even if people don’t want to talk about it, is what gives us a chance to reconcile — not between the perpetrator and the victim, but within the society.

We imagine that if we make people sit next to each other and say, “Let’s look for how we should live together further,” some will say, “Of course we want to live”, and others will say, “We don’t want to live, we want to fight”. This is the problem. We have to agree on our vision for the future and exactly this will be the reconciliation process. But it is a challenging process.

DAY TWO. VICTORY

Oksana: Suppose we recognise the significance of the victory over Nazism as a symbolic event. What place do we, the citizens of modern Ukraine, ascribe to ourselves in those symbolic spaces created by this event?

If we continue the memory line from World War II, we are trapped. The USSR is supposedly associated with Russia. Russia is fighting against us today. So, in symbolic space, we are ostensibly on the side of the enemy of the USSR in World War II. But we are not satisfied with such a lens. And we focus on the crimes of both totalitarian regimes to emphasise that we have suffered from both. That’s true. But here, I’m interested in the question of agency. Who are we? Are we only victims?

Anton: If we are talking about the Red Army or the Allied armies where millions of Ukrainians fought, it turns out that we fought against evil but did not have enough agency to fight for our own agenda. And it’s the same for Russians, Georgians, Armenians. How to deal with that? It’s a complicated question.

SHOULD WE GIVE UP THE VICTORY? NO, NO WAY! IT WAS TOO EXPENSIVE FOR US

Those pathetic attempts by Putin to say that they “would have won without Ukrainians” is a blasphemy for which any veteran or a soldier from the front would have punched his face in 1945 because these people were defending themselves against evil together.

We cannot give up on this agency, but we cannot fully endorse this subjectivity because the Ukrainians, after the victory over Nazism together with other peoples, came and enslaved a part of Europe. In fact, they were involved in the establishment of a totalitarian communist regime. And this is a complicated truth that we find very difficult to accept.

We Ukrainians also have the right to say that victory has been achieved by millions of our lives, and this is our victory, too. But we must say that we are also responsible for the fact that the communist regime of the USSR has occupied the countries of Europe.

INSTEAD OF A CONCLUSION

The victory over Nazism is still not the past. Let us recall the definition of the British historian Eric Hobsbawm for the long centuries: The 19th begins in 1789 and ends in 1914. The long twentieth century still continues, at least in the symbolic field. That is why it is crucial for us today to understand in which system of values we are embedding our vision of history.

May 1945 can trigger various scenarios through which we try to review the future, and we must be aware of our own responsibility. We can see the past in different ways, but it is essential to talk to each other for the future to be possible.