ART RESISTANCE IN KHERSON: IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF THE RESIDENCY IN THE OCCUPATION

In 2022, the Past / Future / Art memory culture platform collected and documented the war experiences of Ukrainian art professionals. This material tells a story of an underground art residency that emerged in the Kherson region in March 2022 and remained active throughout the Russian occupation. It is narrated by Yuliia Manukian, an art critic from Kherson, who spent two months under occupation. In this article, Yuliia interlaces first-hand accounts of the occupation with her interpretations of the residents’ artworks, enriching it with the excerpts from artists’ reflections.

Translation by Polina Baitsym

In 2021, at the Second Culture Congress in Lviv, I interviewed Pascal Gielen, professor of sociology of art and politics at the Antwerp Research Institute for the Arts (ARIA, Belgium). In this conversation, we touched upon the importance of art residencies. Gielen shared with me some thoughts he elaborated further in his essay “Time and Space to Create and to Be Human” for Contemporary Artist Residencies: Reclaiming Time and Space collection (2019):

“Art residencies in this aspect offer practices of contemporary art involved in transnational social movements — when artists and participants of these movements work together over global issues such as the colonial legacy, the Anthropocene, etc. Art reflects more slowly than disasters unfold, but without these practices, it is impossible to make a complete picture of our ideas about them. They connect artists with experts and form unexpected and highly effective interdisciplinary collaborations that go beyond a specific residency.”

The pandemic added a new negative dimension by halting such residencies, and Gielen was deeply worried about it. He emphasized that sometimes art residencies become the only shelter for artists fleeing repressive regimes or war zones. The pandemic, however, threatened to diminish opportunities to escape physical destruction. Gielen also provided examples of artistic resistance to the anti-democratic actions of authorities. Who could have predicted that the following year we would find ourselves at the center of a war that rendered these concerns even more pressing?

Many countries organized residencies for Ukrainian cultural figures, both as a means of survival and as spaces for reflection on Russian aggression against Ukraine. Many Ukrainians benefited from them. But Kherson was not that fortunate. It was occupied almost at once, on February 28, 2022. We were besieged for nine excruciatingly long months. These were the settings in which the unique Residency story unfolded.

MY BACKGROUND

I was born and worked almost all my life in Kherson. In 2015, my colleague, an architectural historian and ethnographer, Serhii Diachenko, and I co-founded the Urban Re-Public NGO. It focused on urban planning, the promotion of cultural heritage, and contemporary art. Our projects have always had a socio-political dimension. We engaged Kherson architects, artists, and creative people in reflecting on issues of urban improvement, preservation of the unique local architecture, work with memory, and revision of the regional museums’ collections.

Upon the occupation, for about three weeks, we were in shock. Then I saw the first artworks on war that appeared across free areas, and I thought that our only mental salvation was to document everything that was happening to us through artistic means. I talked to those artists with whom I often collaborated before, and, at first, six people agreed to participate in the Residency in the Occupation. The artists had already begun to process the new terrible reality, and not merely the events occurring in Kherson. Each tragic event was a trigger.

It was clear to us that we had to keep the publicity for our activities to a bare minimum: in the occupied areas, there were people willing to help intelligence officers at the Federal Security Service of Russian federation (FSB) compile lists of Anti-Terrorist Operation Zone (ATO) combatants, activists, and journalists, and to account for the individuals who could potentially be disloyal to the “new government.” Before Bucha, we naïvely believed that cultural workers were not particularly interesting to these wartime collaborators because their impact on the municipal-level decision-making or the political atmosphere was not conspicuous. But it turned out that in Russia, as in any totalitarian country, they understand perfectly well that genocide begins with the destruction of the cultural sphere. The culture of an independent country aspiring to democracy is a space where the opposition ripens. I stayed in Kherson for another three weeks, and then I escaped and took my daughter-in-law to Odesa. There, during the period of my forced nomadism, I supported the residents and looked for ways to help them, at least financially.

My colleague and I co-authored Kherson Diary for The Observer/The Guardian — a series of first-hand accounts of the occupation. We risked our lives, but it was a justified risk that prevented us from going insane in the occupation circumstances. When we escaped the city and arrived in London for a temporary residence, we met the editor of The Observer, Paul Webster. Shaking our hands, he expressed his admiration for our courage.

WE MUST CONSISTENTLY EMPHASIZE THE IMPORTANCE OF ENSURING OUR INDEPENDENT VOICE REMAINS UNDISTORTED WITHIN THE INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL AND ART SCENE

I believe that we must consistently emphasize the importance of ensuring our independent voice remains undistorted within the international cultural and art scene, where Russia has long been a dominant representative of Eastern European artistic practices.

Paul Webster was touched by my conviction and approved the idea of a publication on Kherson art resistance in The Observer. That is how the article Kherson’s secret art society produces searing visions of life under Russian occupation appeared. After its release, I received countless emails and messages from all over the world, requesting interviews with the artists, most of whom remained under occupation. All the dire consequences of this disclosure considered, we postponed further publicity until the de-occupation.

In October, the team of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) informed me that my essay, titled “Residency in the Occupation: Art under Threat of Death,” was awarded third place in the 2022 international competition AICA Young Art Critics Prize. The jury was impressed by Kherson artists who carried on with their work under occupation. The award organizers kept the artists’ personal details confidential and planned to hold a closed display of the Residency works at the international AICA Congress “What Are We Talking About When We Talk About Criticism in the 21st Century?”

Conversations with creative people of Kherson, currently scattered around the world, also inspired the Animation of Art Resistance in Occupation project, carried by us, the Urban Re-Public team. We aim to create a series of short, animated videos based on the Residency artworks to promote Kherson art more broadly.

Some of the animated pictures are already available on our YouTube page

This project concentrates largely on the representatives of Kher-art (Kherson unique art), which has a distinctive character of non-conformity, irony, and subversion, combined with depth and complexity. These artists have in their inventory wide-ranging palettes of wartime artistic reflections. Within the project, we similarly had to shield some people with secrecy, since they had been working in the occupation before the liberation of Kherson on November 11. For those who remain on the still-occupied left bank of the Kherson region or have family members there, these precautions remain essential, in light of the horrific stories of abductions and civilians’ slaughter.

THE RESIDENTS

OLEKSANDR ZHUKOVSKY

The first to respond to the residency’s initiative was naïve artist Oleksandr Zhukovsky, renowned for his unique method of painting with bleach on textile. When I reached out to him, he was already working on a mixed-media work titled The Unwanted Guest:

“This is my first reflection on the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, created during the first month of occupation. This work is symbolic: it shows how a murderous wasp encroaches on one’s territory, trying to take over their land and homes, but receives a worthy rebuff from the united inhabitants of the ‘little house.’ The martial coloring of the insects is indicative. The people of Ukraine are so united now that they can overcome any unwelcome guests.”

Oleksandr’s basement studio became our underground art shelter, where we gathered and discussed ideas, shared news, and encouraged each other. As we saw the “murderous wasp” on the studio wall, we were in awe of the artist’s unparalleled courage: Russians, who were frantically searching for partisans on collaborators’ tips, could break in at any moment.

The artist’s second artwork is a poster titled pukin (the initial title was putin Cock-A-Doodle-Doo). Zhukovsky created it a few hours after the atrocities in Bucha were disclosed. That day, he rushed to his studio and rapidly made this poster. In the best traditions of Kher-art, the artwork draws upon the grammar of incarceration as the only serviceable narrative about putin’s personality, unworthy of humane treatment. The statement’s bigotry — putin wears make-up and feminine attire, assuming the “at-service” posture — is a deliberate subversion; Zhukovsky contends that for people like putin, with staunch “spiritual clamps,” this is the most flustering punishment. Death would be too merciful. Frankly, I was afraid that The Guardian would reject this painting, given its political incorrectness, but no protest was voiced from their side. Fortunately, they accepted the author’s arguments as justification for the harsh message:

“I created this work while being overwhelmed. I especially hated this subhuman when I saw all these terrible things that had happened in Bucha and in all the villages and towns where the bloody hands of putin’s executors reached out, the so-called “liberators” of Ukraine. Picturing this monster behind bars, I wanted my wish to come true as soon as possible. At the same time, I anointed his forehead with brilliant green solution. According to Russian criminal subculture, it implies condemning someone to death. I think that many Ukrainians and other people around the world share my desire.”

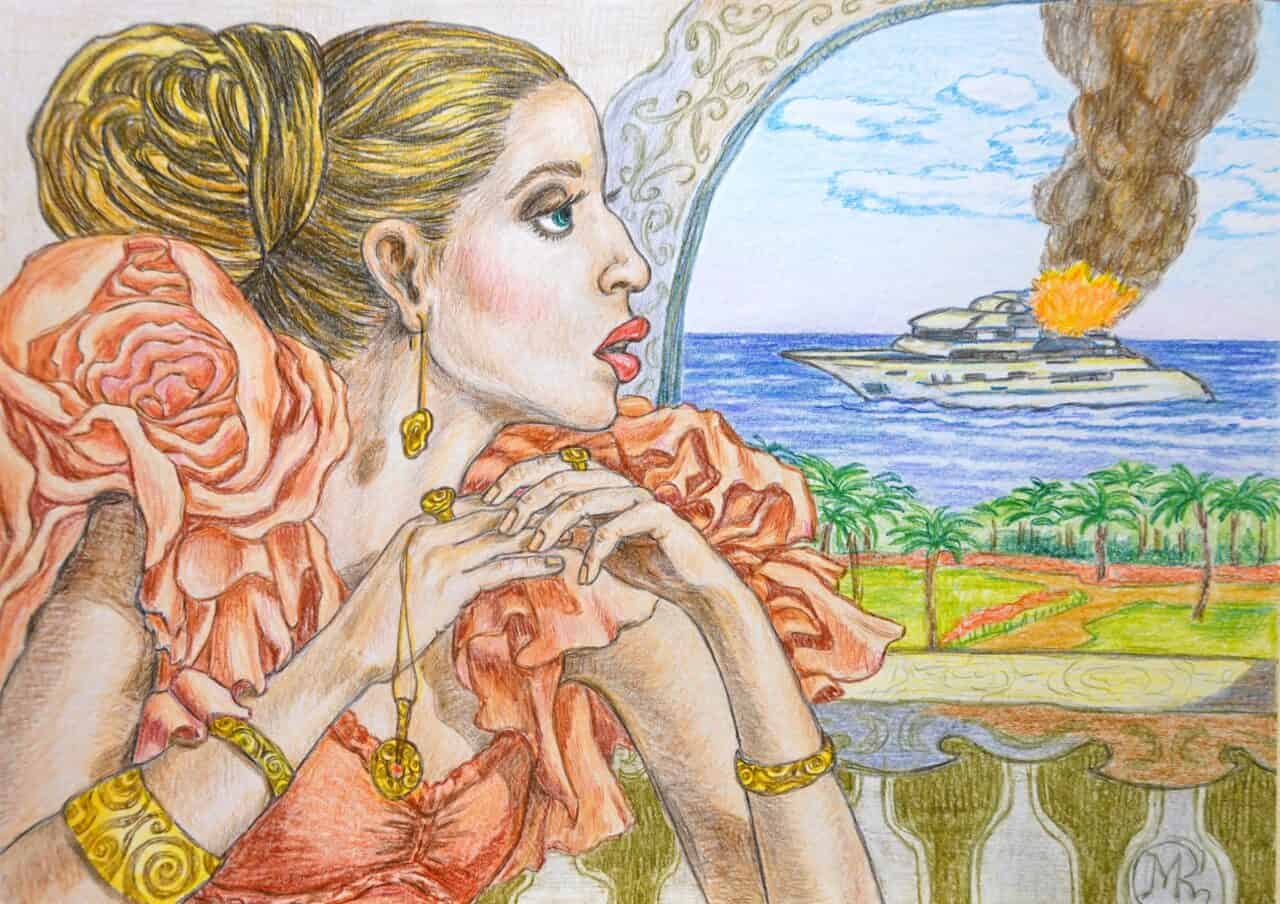

The third work of Oleksandr is Humanitarian ORCcupation:

“I created it at the apex of the occupation, in May, when the resistance in Kherson was suppressed through grenade explosions, automatic fire, gas attacks, kidnappings, intimidation, and physical violence, intermixed with the so-called ‘humanitarian aid’ from the ruzzian world, which took the form of poor food supplies. All this was happening under the guise of the “salvation” from some Nazis whom no one had ever seen in free Kherson.

I painted it over an incomplete work, which was more than 20 years old. I started the latter when I was still living in the village of Bilozerka, wishing to convey a message about the zombification of advertising that holds people captive to its lies. But I never finished it, completing only about 50% of the work. Thus, 20 years later, I repainted it in alignment with current realities.”

The image of the Woman of War, in my view, is a rather explicit allusion to the Whore of Babylon, who personifies the arrival of the totalitarian Antichrist with all his infernal gifts — an instance of contemporary eschatology, imbued with continuous wars. The blood threads flooding our land are far from figurative. Now, as Kherson is de-occupied, the fall of the Whore seems relevant to the prophecy.

By the way, many clerics, theologians, and other religious figures have declared that putin is the Antichrist, grounding this conclusion not merely in the Epistles of John the Theologian but also in political discourse. Each time Russia intervenes somewhere, they say: “Ah, that is the last conflict.” It is quite clear why he, putin, was so odiously “glorified.” The only critical “but” is that we and the entire civilized world are unlikely to allow him to become an “earthly king.” People just need to outline the extent of his crimes. According to Matthew Sutton, professor of history at the University of Washington and author of American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism (2014), the apocalyptic obsession ebbs and flows in moments of crisis: “We are at another moment where prophecy is invoked to make sense of current events.” The literalism of metaphors also intensifies.

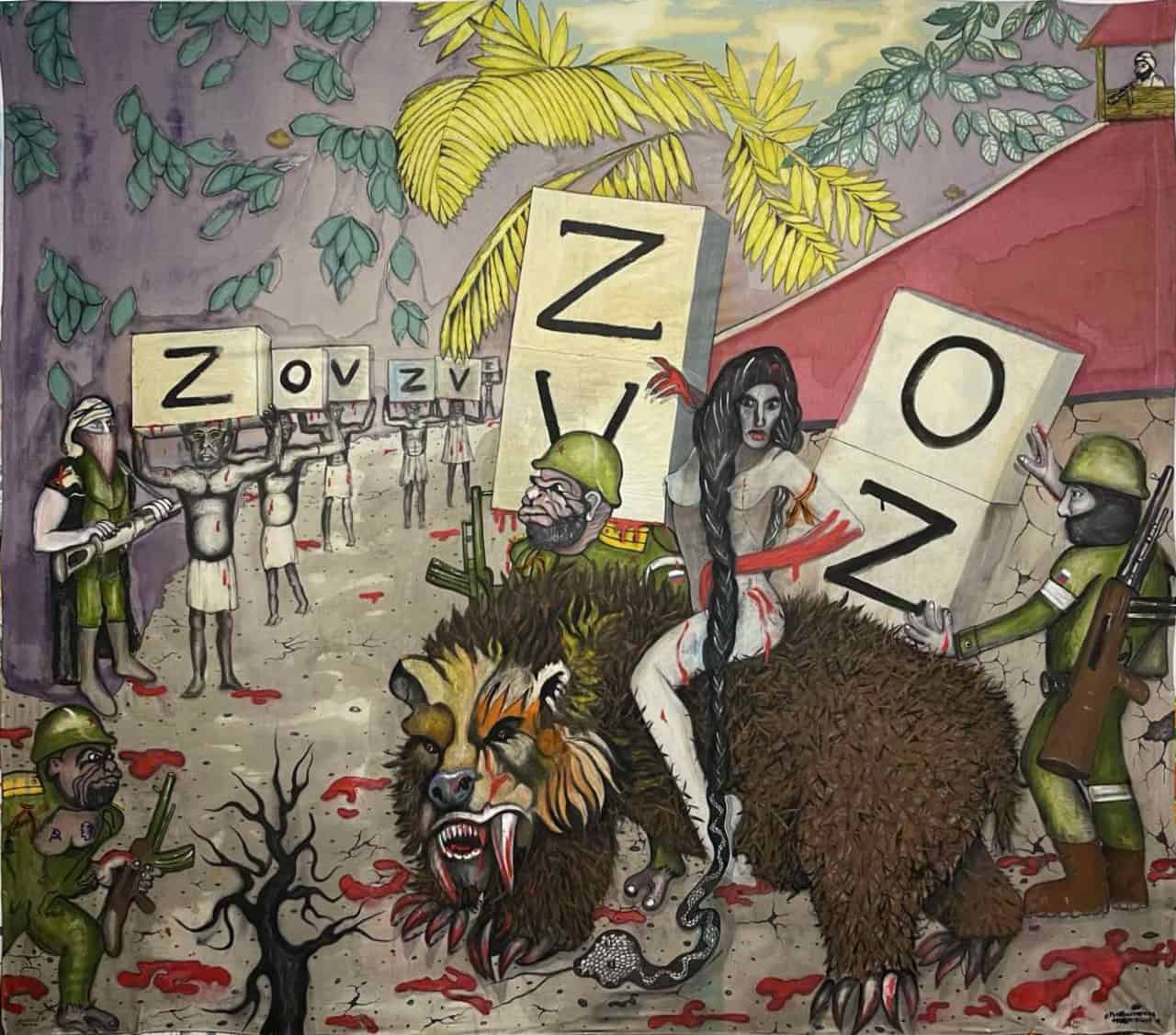

MARKA ROYAL

What has made it impossible for us to live in time like fish in water, like birds in the air, like children? It is the fault of the Empire! Empire has created the time of history. Empire has located its existence not in the smooth recurrent spinning time of the cycle of the seasons but in the jagged time of rise and fall, of beginning and end, of catastrophe. Empire dooms itself to live in history and plot against history. One thought alone preoccupies the submerged mind of Empire: how not to end, how not to die, how to prolong its era.

J.M. Coetzee, Waiting for the Barbarians (1980)

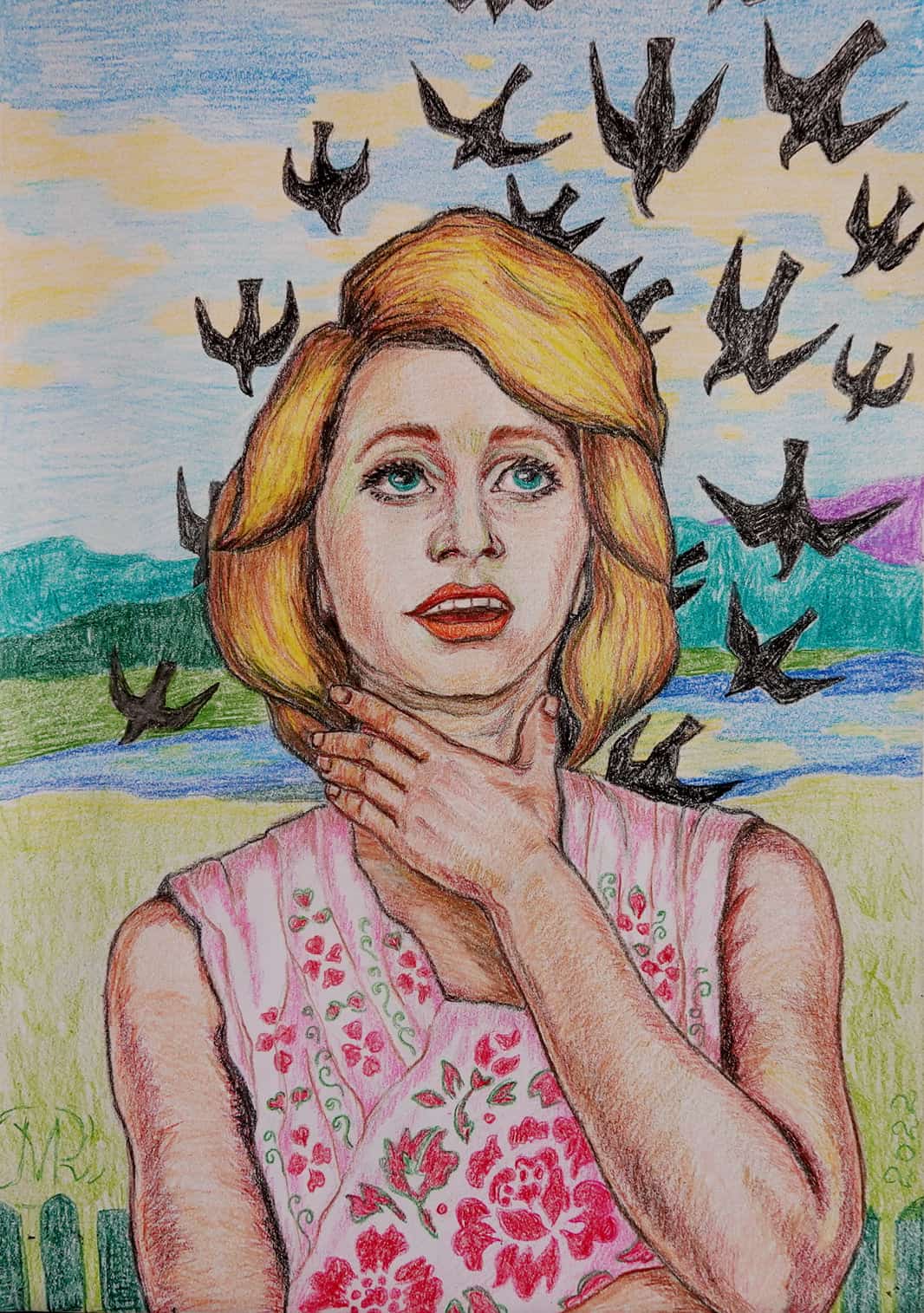

Marka Royal, an artist from an occupied village in the Kherson region, released all her pain into Z-Notes by Mrs. Solodukha. Her first drawing with the expressive title It Is Impossible to Leave or Stay opened a The Guardian article on Kherson’s secret art society under occupation.

In what follows, I present the artist’s monologue, with her consent. She doubted she would witness our victory herself — the occupiers’ maltreatment of village residents is well-known.

“My sister’s words, uttered over the phone, were like a blow to the head: ‘War!’ I fell into a shock stupor and sat down on the bed. My first thought was: did my daughter manage to leave Odesa yesterday? She did, thank God. It was the day that divided life into “before” and “after.” My youth and enthusiasm remained in “before.” And all plans for the future dissipated with the smoke of every explosion. It rang in my head: “Why have you been living and creating? All this and for what? What is next?” I rushed to grab my documents. Then, upon recognizing that art had been ennobling my home and soul for more than 15 years, I took my last paintings from the walls and moved them down into the basement to save at least some of my canvases. After I had almost buried them there, I decided I would not do that again. My heart became imbued with bitterness and fell into the abyss. My eyes were wet for three months. The food tasted like ash. Every day we browsed the news, shivering with terror, waiting for our turn, sitting on suitcases, stacked in the corridor.

I am used to the bruises of fate. But war! I did not make any wishes for the New Year, and, for the first time in my life, I celebrated it in a black dress. The military operations unfolded around us as we hid in the basement. It was terrifying, especially at night, to hear the fighting and watch the bullets streaking from all sides. At the end of our street, close to us, two houses were burned. Neighboring villages were affected. We survived, seemingly by a miracle. Once, we got tired of counting the military vehicles driving down the road from Kakhovka and the armed combatants in the area. My rage at the war made me sick. Then I realized: rage was killing me from the inside. I could not afford to get sick. Everything was closed.

After a month and a half of treatment, I began to philosophize: What does God plan for my life now? My dreams went wild. It was time to let everything and everyone go. The house turned into a waiting room and the bed into the crow’s nest. There, I constantly listened to the space and lay undressed. We decided not to hide in the basement because it could be destroyed with the house, and we would suffocate. The heart became intoxicated from recurring explosions, war news, and tears. We sank into total apathy.

Then everything seemed to go back in time. The atmosphere of the 1990s prevailed. Many people roamed like zombies, dumbfounded and with deep gloom in their eyes. The amount of alcohol increased, and it was sold directly from barrels in markets. Pubs opened in the area, almost next to us. Today, wearing second-hand clothes, I drove on a scooter to get food at the nearest store. I do not understand where so many Russians in civilian clothes came from. Two completely sober dudes were sitting on a bench. With beer cans still unopened, they followed me and began waltzing around the store, improvising jokes. Annoyed by their bad acting, I ran out of the store without buying anything. They returned to their bench. While I was starting the scooter, one of them, imitating the scooter’s roaring, shouted five times: ‘I haven’t fucked anyone today.’ His plate-sized eyes stared at me. I drove home, sadly thinking that their heads were filled with the same concrete that covered the road.

THE WAR ERASED MY WHOLE LIFE, BUT MY TINY STUDIO BECKONED ME

The war erased my whole life, yet my tiny studio beckoned me. But how can you paint if you hear explosions? I started painting flowers and broke two spatulas at once. The flowers also resisted. I did not like them; they were annoying. I thought: Who am I trying to fool, and why? The war could not be thrown out of my soul and life.

Why do I detach myself, even in creativity? It is imperative to record my own experiences on paper. The senior woman in my family, 86-year-old Solodukha, inspired the title of the future sketchbook — Z-Notes by Mrs. Solodukha (ZNS). The first subjects followed the title’s discovery. I recognize that the work in my circumstances has to be delicate and allegorical. But it still does not insure me against risks. The subject is complicated. The subject is war! And war is war even in the sketchbook, regardless of how you obscure it. For the first time, I feel the powerful tentacles of asceticism in creativity. Now I have to think a hundred times before making sketches. Russians have already threatened to persecute other creative amateurs. So, sit quietly and stop tweeting, as they say. But it is immoral to shoot a sitting bird, no?

I am going to brew coffee again; it is fake, surrogate. They do not import anything else. My legs stop at the home library. From time to time, my gaze falls upon Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, and I stretch my lips to blow the dust off the pages again. Currently, I have free time to work on the ZNS. I want to have a series, a collection of my experiences. After all, time is historical. A troubled question about the future arises. Many have left. And they will not return. Somewhere in my dreams, the city waits for me, lures me. The barrier of countless “buts” blocks my way. Despite the insurmountable circumstances, the nervous pandemonium continues. As does my hopefully artistic “epic” about the present-day reality. I put my faith only in the gods’ mercy.”

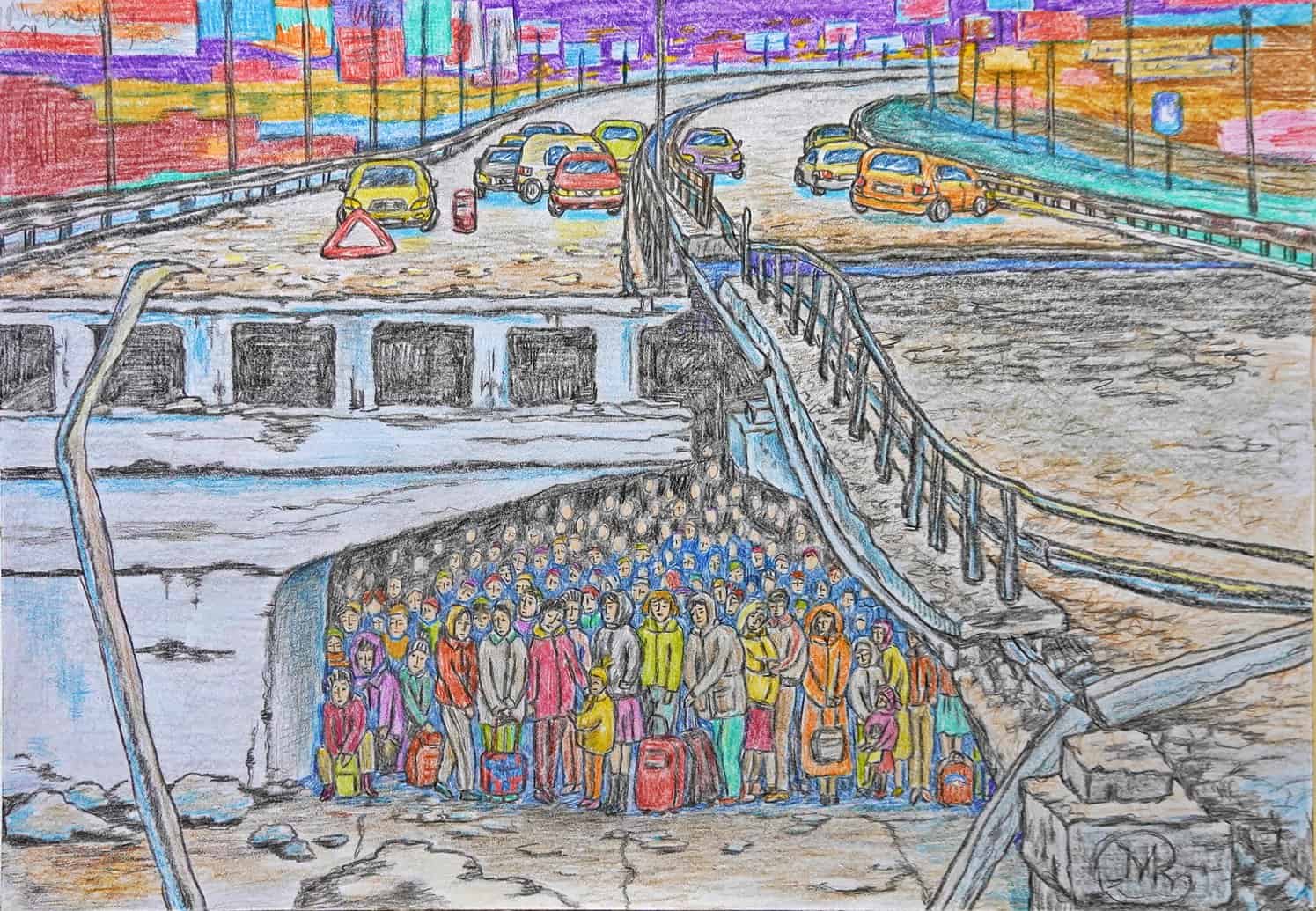

Marka Royal’s artwork, The Crossroads, refers to the widely circulated photo of the destroyed bridge that connects Irpin and Bucha with Kyiv. The artist shared that, upon completing it, she burst into tears — “Is it really happening to us?”

“One should sometimes trace the irony in my works. I am not inclined to judge anyone, especially in my creativity. As an artist, I reflect what I observe, hear, and see through my creative lens,” comments Marka on her work, Vasyl Pozhyva Plans to Return.

On the artwork, The Easter Motif in Chornobaivka:

“The subject came up two days before Easter. Well, in what other city should this work be done, if not where one of the largest poultry farms in Europe, with more than 4 million chickens, ceased operations due to the war? And Chornobaivka itself became famous. The details fitted Mrs. Solodukha’s Z-Notes.

To sum up, when a man puts on a soldier’s uniform and picks up a weapon, his name and facial features are practically erased from the chronicles of important information. Especially, in the case of the dead. It has been observed that no explosion is heard on religious holidays. But the day before yesterday, Russians got drunk, drove through the streets, shot into the air, and shouted: ‘Fuck this war!’”

“The Vyshyvanka Day is a real episode from life. For Vyshyvanka Day, a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature, fully dressed, as he was every year, dropped by Solodukha for a cup of coffee after work at the local museum. They decided to open a humanitarian food can, which the grandmother brought and strongly recommended to try it. The teacher cut himself…”

YULIIA DANYLEVSKA

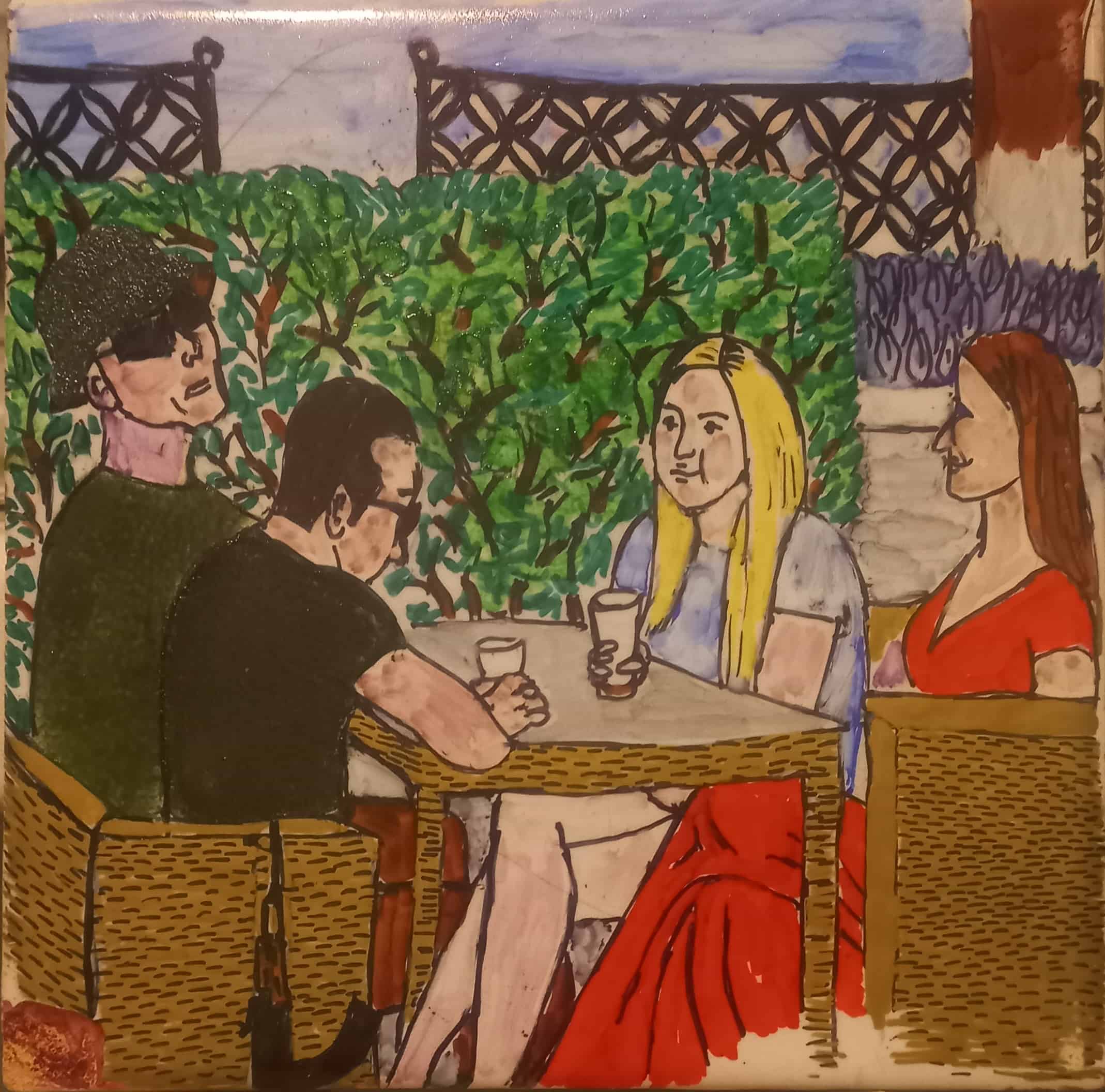

Yuliia Danylevska’s tiles constitute another terrifying chronicle. The artist depicts stories from life, her dreams, and gender-sensitive reflections. She uses markers and works in a comic-naïve style, uncovering the hypermedia of our reality, which chokes on violence, conspicuous and concealed. Some pictures are almost memes, with their spot-on targeting of the societal pressure points. Her My (de)occupation diary includes both works created during the occupation and tiles from the pre-war period, as a documentation of the anxious state in which society has been since 2014.

“Snow Pickers. Mariupol is the first work I painted after the start of the war, near the end of March. Then, little by little, paintings and diaries by Ukrainian artists on Russia’s aggression against Ukraine began to appear on social media. I did not want to talk about it, even through visual images; the shock of what was happening around us was so strong that it seemed impossible to start drawing. We lost a lot of people daily, and their families did not need art, and we did not know what would happen to us during the occupation.

Thanks to the journalists who stayed in Mariupol for a while and private YouTube channels, we, Khersonites, saw besieged Mariupol decaying day after day under shelling.

I was stunned when I learned that people collected snow to heat it and extract dirty water to survive. They used it to wash dishes or to cook pasta and porridge. The longer the snowy weather lasted, the longer people stayed alive. To remember this fact, I depicted the process of snow collecting as I thought it occurred.

After more than 6 months, I ask myself whether the same thing is likely to happen again. What if people will be collecting snow in some other city this winter to survive hunger and dehydration?”

“In occupied Kherson, one could hear no air alert. But, at the end of March, we still heard it several times a day. The air alert has already become a part of the daily routine for the residents of Ukrainian government-controlled territories. However, in March, we also hid from shelling in basements, bathrooms or corridors, because we learned the ‘rule of two walls’ very well.”

“When I watched the actions of the occupiers, that followed history textbooks, it seemed to me that the enemy army finds some unknown to us thrill in destroying our homes, our cities, and our lives; it is a sort of cheap hard drug one gets addicted to immediately and irreversibly. It is never ‘glamorous’ and completely erases the personality of those who use it,” says Yuliia.

Yes, they have been hooked on us, on Kherson, on the thrill of unpunished violence, drunk on our blood — the heaviest and most inhumane drug of all times. I know no better metaphor for their ideology than Yuliia’s interpretation in her artwork Drug Z.

“Who knows how many sinless and pure souls died because of Russian aggression? Pets, locked in shelters or their own homes, waited until the very end. Their owners left residencies and never returned: some were murdered, some were traitors. Sorry, little ones, we, human beings, let you down again.

I decided to draw goldfish, gradually dying… This is some sort of euphemism from my side because I failed to depict skinny dogs and cats. In the background, one can see a window sealed with tape.

I dedicate this tile [Nobody Will Come] to all living beings that waited in vain for help.”

“The plot of this tile [The Trophy] arose after we and the whole world learned about Bucha. After five days, I recovered a little and could draw at least this — a hand of a Russian soldier tearing the earring out of the ear of a Ukrainian girl. I cannot depict the murder and rape of our people yet, even for the sake of educating European audiences. Still, it is not difficult to guess what happened to our women next. In the background, I drew a person who, seemingly, moved here from the first picture (The Snow Pickers. Mariupol). On the latter, he looked at the destroyed building. On this tile, he is on the ground with his face down behind the girl, with his hands tied.

To depict this plot, I had to wear an earring we found in the street a long time ago. I have not worn earrings for ten years, perhaps; I do not really like jewelry. It turned out that my earring holes healed over. Almost…”

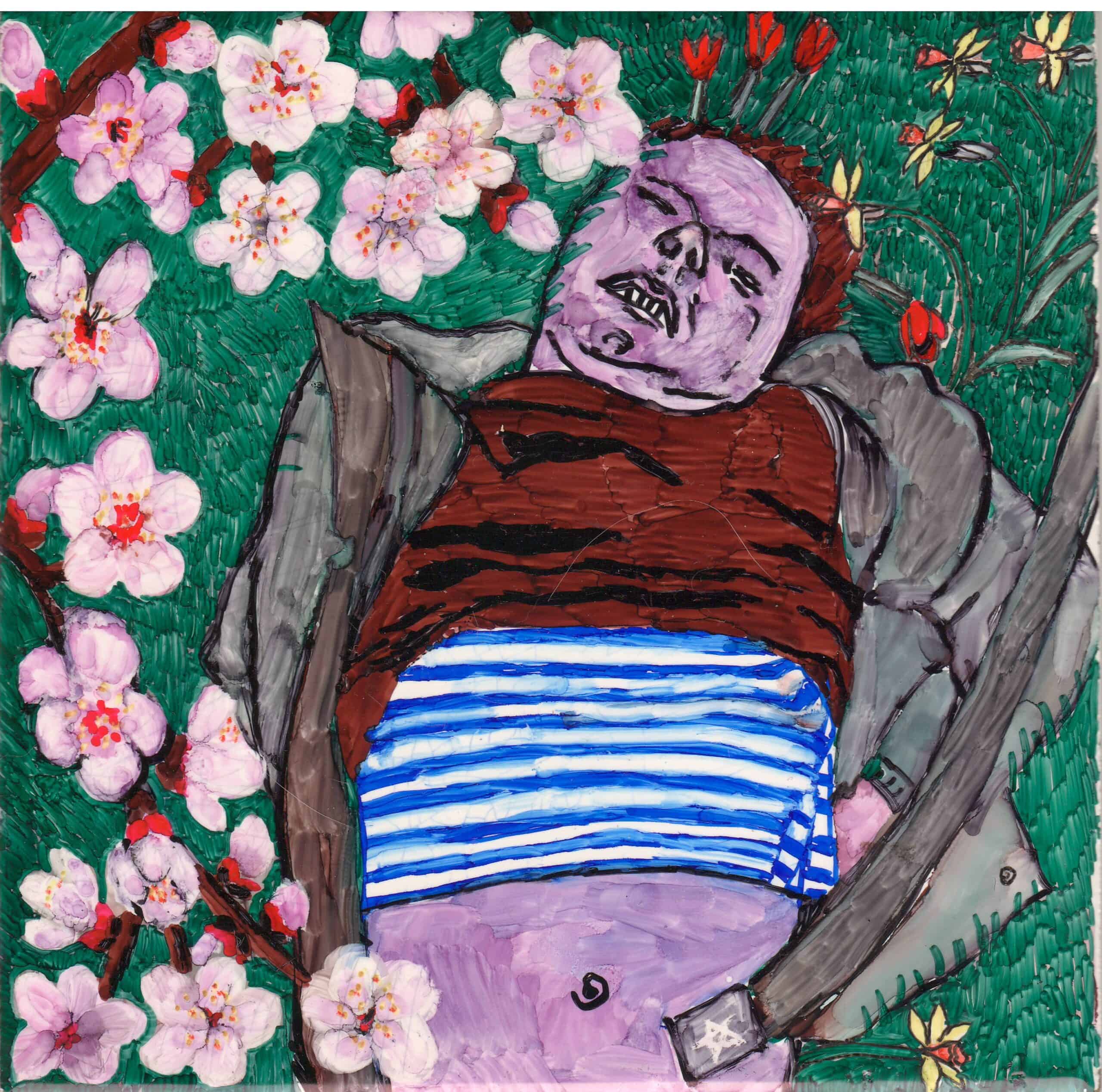

“This plot [The Tourist] is based on a viral photo of the murdered Russian paratrooper and marauder Denis Tsybenko. I wanted to draw attention to the contrast between the beauty of our nature in spring and dead bodies, so-called meat for the grinder. In intercepted telephone conversations with their wives, Russian soldiers often praised trophies, stolen goods, good living conditions in the captured houses, and even the quality of local food. It was clear that they became so comfortable here that they started to perceive the war as an exciting adventure.

‘Oh, you will sing even sweeter songs when everything starts to bloom profusely here, and the city streets will be full of sweet aromas of cherry and apricot orchards,’ I thought. I wanted to show the absurdity of death and the impossibility of enjoying the beauty and richness of life… However, this is a classic dualistic plot, where the unceasing rapid development, the awakening of flora and fauna down to their tiniest manifestations… and decay, anhedonia, and the end of all living things go side by side.

‘Oh, these Ukrainians… they have a ‘delicious’ ice cream, and juice, and a laptop in every home, and they eat Nutella… and nature here is also beautiful!’”

“The image of Zmiy-Horynych, a fire-breathing dragon with three heads, is easily recognizable even by children because it is a character from Russian fairy tales, a symbol of villainy, greed, and rage, which brings only death and misery. It attacks our cities, destroys, and sets the whole districts ablaze. I created this work under loud explosions in Kherson. The occupiers detonated an unknown projectile not far from my house to blame it on the Ukrainian Army, and 10 minutes later, quisling mass media were ‘working on the spot.’”

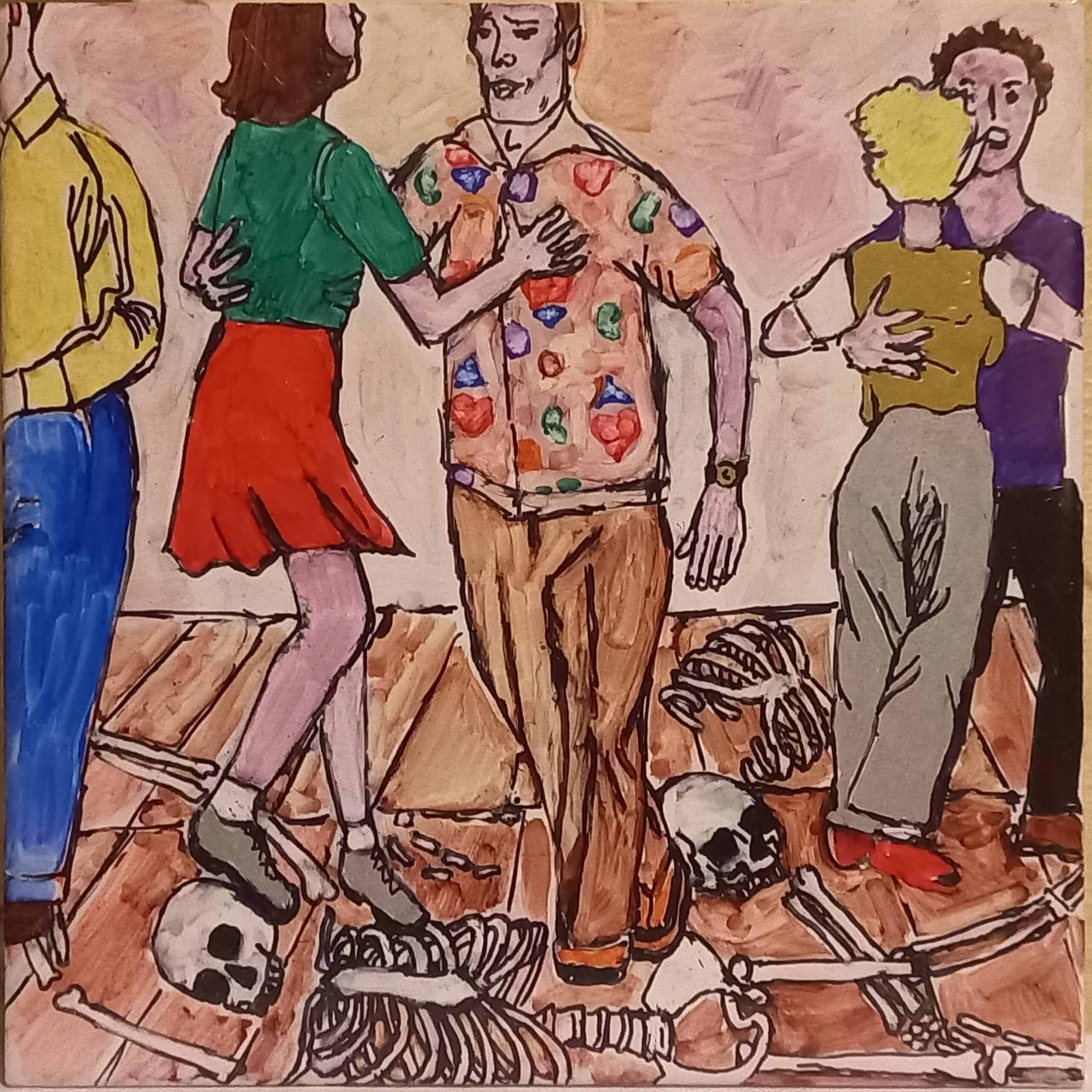

Under the duress of constant and terrible tension, people try to keep their sanity intact differently: some through hard work, others through hedonism as the last refuge from madness. Yuliia redrew the image of Dancing on Bones from the opening credits of David Lynch’s picture, Mulholland Drive (2001). Looking at the leg kicking the skull, I can imagine Lynch nodding approvingly: the “compassion fatigue” is illustrated perfectly.

“There is a saying –‘dancing on bones.’ It is a distorted version of another saying – “life goes on.” I like to use literalism in my works from time to time. This artwork is an attempt to analyze where is the line between daily life, which continues, at least for someone, and entertainment, fun, and hedonism. Who has the right to live their normal lives as if nothing happened, and who does not? Can we return to our routine after witnessing and becoming victims of hostilities? We ask ourselves similar questions every day, and every day we look for answers that are still temporary.”

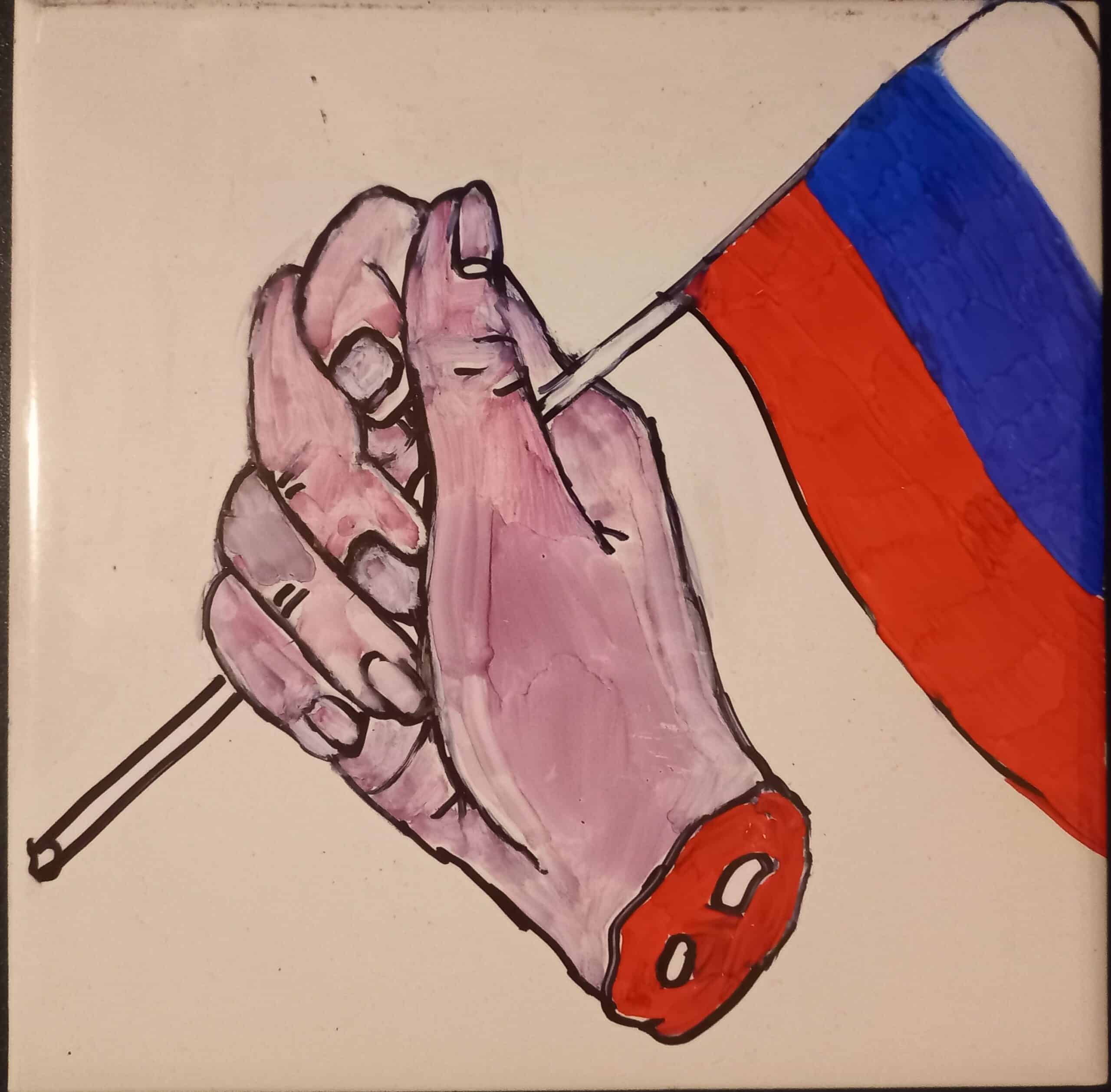

“This simple work [Good Luck with That!*] draws upon Russian propagandist holidays and celebrations, which the ruzzians started to organize after several months of occupation. Since the summer, tricolors began to appear not only on administrative buildings but anywhere in the city.

I was walking through the city square, where the celebration of a memorable date for Russians was taking place. There were many people, pensioners, and armed soldiers. Teenagers performed Soviet hits on a small stage. I saw a drunken, unkempt man carrying a baby in his arms. He handed his son a small tricolor and said, ‘Come on, wave the flag. Do you like it?’

I decided to draw a possible continuation of this scene, but without indication of who cut off the hand — the so-called “us” for collaborationism or the so-called “they” who do not really care who to kill. Even the most obedient people can fall into disfavor with the executioner.”

*Good Luck with That! refers to the Russian idiomatic expression “Take a flag in your hands!” (ironic prompting to take foolish chances).

“Oh, Lovely Maidens, Fall in Love, but not with Muscovites* is inspired by a photo I took at the beginning of summer at a local cafe. One guy was a Russian soldier, Caucasian in appearance; the other had narrow eyes. The occupiers invited local girls to a cafe. It is not unusual. Close ties between the occupiers and the occupied were present in all wars. I asked my Facebook followers whether we were entitled to condemn them. Opinions were divided, although no one would openly excuse the girls’ behavior. Is it acceptable to have such a relationship during the war? Or, maybe, such questions are kind of slut shaming**?”

*From the poem Kateryna by Taras Shevchenko, 1842.

**Slut shaming means making a person (especially a woman) feel guilty or inferior for sexual activity, desires, expression, or circumstances that deviate from traditional or orthodox gender expectations or religious or cultural standards.

This artwork, The Gifts of Autumn, is a brilliant example of Kher-art irony: “At school (and sometimes even at university), Ukrainians are often given a creative task to make ikebana and souvenir crafts about the ‘golden autumn,’ the ‘gifts of autumn,’ etc. One can trace the narratives of the harvest, the fertility of the Ukrainian land, and the beauty of nature in this assignment. According to the Ministry of Education, those are eternal topics for us. This year my son has again received the same task despite the war and remote education. He decided to ignore it. But I drew the picture — this is the way, I guess, these ‘gifts’ should look like.”

MONA

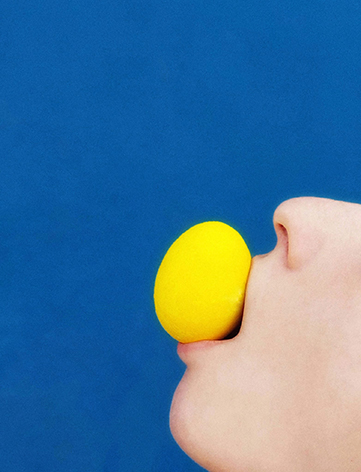

The artist, under the pseudonym of Mon,a works with painting. Her works echo her inner state. She is also a children’s book illustrator. Mona created a video art …I want to scream:

“I try to convey the tension and horror people face now. A series of losses, fears, screams, the roar of hail, and the whistling of missiles is enormous pain. Unbearable pain.

I am scared. Every day I am scared by bombardments, but even more — by uncertainty. I do not know what today will bring; I do not know what tomorrow will bring. Russians have occupied Kherson. The city seems to be alive: people work, and traffic moves. But I do not feel at home. I do not feel protected, I do not feel free. The days merge and recur. There is a feeling of a locked cage. There is not enough air to breathe. I want to scream.

February 24 became a black day on the calendar… A rapid change of images is the way we live now. Now we need to cover more information to be always ready. Everything changes each second. The emotional state of people switches just as quickly.”

The artist created the artwork Transition as a reaction to the missile attack on Odesa that murdered three generations of women: 3-month-old Kira, her mother Valeria, who was 28 years old, and Valeria’s mother. The baby in the painting turned into a newborn star.

OLSON OLBERBURG

Artist Olson Olberburg works with painting and collage. She preferred the latter to capture the reality of the occupation. Here is what she says about the Look series:

“This is the first computer work since the beginning of the war. After February 24, I grabbed paint several times. It was painful, and I painted directly on my teardrops. Then there was a long pause for a month. Many of my artist-friends started creating their war reflections, and I also wanted to, and even tried, but I could not: my hands were shaking, and my eyes were full of tears. At that time, we were hiding from missiles. The Internet was still available, so I decided to try to express my feelings in computer language.

In the first days of the war, we all tried to tell our friends and relatives from Russia about what was happening. We thought it would help halt the war, but my relatives did not believe me. Many of them said: ‘Soon you will become a part of Russia, and you will have a good life.’

In my house, the neighboring entrance burned down, and people died. The occupiers fired at the building, and a fire started; they did not let in firefighters, and the neighbors were scared. We were all in touch. People needed all their courage to dare to leave their apartment and try to save others…

Not all were saved. In front of the house, Russians shot at cars with people who did not have time to leave the road along which the armored personnel carriers were advancing. I saw all this horror with my own eyes. I show them in Russia, tell them, but they repeat: it is all fake. Then I created the Look series, taking photos of destroyed Ukrainian cities and fragments from one of my hand-made collages. It was my inner cry.”

For the official poster of the Animation of Art Resistance in the Occupation project, we chose Olson Olberburg’s collage Freedom, which she created in occupied Kherson on March 24:

“It was an intuitive work. I participated in several rallies, and when you see almost the entire city in yellow and blue around, hear singing and sense the resistance to the occupiers, you feel victorious. I tried to show the Kherson region which can overcome everything.”

Indeed, this work represents the entire Kherson region because it incorporates its well-known images: Cupid sculptures from the European hotel (1915), a wooden Cossack church in Beryslav, and seagulls; all of which are currently under occupation. The heel of one of the cupids became a symbol of the Kherson Museum of Contemporary Art and is on its logo and pins. It is also about the continuity of artistic traditions, the connection between the past and the present, and between the historical heritage and the Museum’s collection.

OLEKSANDRINA KHRAMTSOVA

The occupiers ruthlessly burned the Kherson Plavni — our source of pride, for it is a wild nature area almost in the city, in the Dnieper delta with numerous swampy islands, small meadows, and floodplain forests. The residents were left to glare in powerless despair at the smoke that spread over the mutilated land. The artist Oleksandrina Khramtsova, who spent almost five months in the occupation with her husband Semen Khramtsov, an artist and curator of the Kherson Museum of Contemporary Art, and their baby son, intended to make a series of paintings dedicated to the destruction of Plavni during the occupation. However, she implemented this idea only after escaping Kherson, within the Sorry No Rooms Available art residency curated by a local artist, Petro Riask,a in Uzhhorod, Ukraine.

In light of the sad story of Viacheslav Mashnytskyi, an artist and director of the Kherson Museum of Contemporary Art, who went missing in his dacha in the Plavni (Potiomkin Island), I perceive Oleksandrina’s series The Plavni as a foreboding of the fate of those who hid there from the occupiers.

Semen Khramtsov shared that he and his friends (artists, musicians, creative people) tried to spend as much time as possible at Viacheslav’s dacha to avoid clashes with Russians in the city. And then someone spread rumors that an enemy detachment landed on the island, either 20 or 200 combatants. For hours, they waited for the Russians to arrive, petrified. Eventually, Semen decided to go to meet them. Everyone lined up (given the very narrow paths there) and went towards the pier, from where they could reach the city by boat. Almost immediately, they encountered machine gunners. It was impossible to move forward, and someone had to give way first. Semen was holding the baby in his arms, his adrenaline was running high, but he looked directly into the eyes of the armed: “May we pass?” The soldiers stepped aside, and the dacha dwellers reached the pier in complete silence. It was such an obvious sign that no safe places existed anymore that the Khramtsov family began to develop an escape plan.

EACH PAINTING SHOULD SEAMLESSLY FLOW INTO THE NEXT ONE, FORMING A CYCLE AND CLOSURE

Almost all their friends also left the city. Some managed to reach free Ukrainian territories, and others made their way through Crimea to Europe.

Unfortunately, Viacheslav Mashnytskyi did not have time to do this, and, frankly, he was not in a rush. As a museum director and owner of the valuable collection, which includes works of leading Ukrainian authors from the 1990s, unique examples of Kher-art from the 2000s and the 2010s, and more than 50 works of Ukrainian contemporary artists (a gift from the Open Group), he felt a great responsibility. Viacheslav did not want the occupiers to either destroy it, somehow, through traitors, or move the pieces into an unknown direction, as they did with two regional museums (fine arts and local history). He tragically disappeared. We hope that the Ukrainian intelligence service will carefully investigate this case.

Oleksandrina, the artist, shares: “Each painting has a size of 20×40 cm. I have not yet determined their final number. Each painting should seamlessly flow into the next one, forming a cycle and closure. Everything else on the canvas loses its sense of existence, except the endless line of the horizon – the Plavni expand, seemingly without altercations, focusing the gaze so much that the landscape becomes paradoxically static due to its frantic dynamics. However, there is not a single fragment repeated. And, amid this tranquil beauty, explosions sound, the Plavni go up in flames, and a thick blanket of black smoke covers the sky…

My husband, our baby, our cat, and I had to leave our home in Kherson, the city in southern Ukraine where I was born and lived before Russia invaded Ukraine. It was under occupation from the first days of the war. After weighing all the risks, we decided to get out of Kherson to the territory controlled by Ukraine. Upon passing more than 30 Russian checkpoints, we found ourselves safe in Zaporizhzhia. But we were homeless and sought shelter in Nikopol, Dnipro, and Kyiv. We lived in Lviv, and now we reside in Uzhhorod, in western Ukraine. We are waiting for the de-occupation of Kherson to return home. This work is my reflection of the site where we spent so many happy days. The site that is now being burned by the occupiers, who continue to destroy everything we love.”

Looking at these works, you can sense the reek of scorching and the aftertaste of ash on your lips. The horizontal line seems to invoke a distant tragedy, but how many of our friends choked from that “smoke on the water.”

Oleksandrina Khramtsova, The Plavni, September 2022

The Plavni series was displayed at a collective exhibition of the Sorry No Rooms Available Residency in Uzhhorod. Together with Oleksandrina, Semen Khramtsov and Viktor Pokydanets, an artist from Mykolaiv, took part. Viktor called their works the “Southern View.” They indeed seem to be interconnected on many layers of meaning.

Khramtsov’s artwork Black Circle, or The Dot, is a series of statements: about the end of statements as such from his side; the maximus, as Malevich’s black square; a black hole which absorbs any attempt at an adequate artistic reflection. It is also an homage to the Slippers series by Pokydanets — an ironic intervention in Semen’s minimalism. Viktor, while picking out shoes for himself, pulled out black insoles and fit them perfectly into the Black Circle, symbolizing the last thing you see when a pitiless hole rips you out of life. The feeling of normality literally showed its heels.

The artwork of Pokydanets continues to “finalize and dispose” of false high-spiritual messages of Russian culture. A powerful image of the mass shooting itself. Total self-cancellation. Oleksa Mann, an artist from Uzhhorod, presented Pokydanets with the book The Kolomensk Benefactors (a history of philanthropy in Kolomna in the 19th century) for his artistic practice. One perceived the call to Russian capitalists to “do good by supporting the poor and destitute” with an overwhelming sense of disgust. Viktor’s trademark irony manifested itself here, too: bullets cut through the book from the In the Field of Education and Culture section. Churches, schools, museums, children, paintings, icons… everything was killed by the very essence of the empire. The exhibition visitors flipped through the “benefactors” and commended every “hit.”

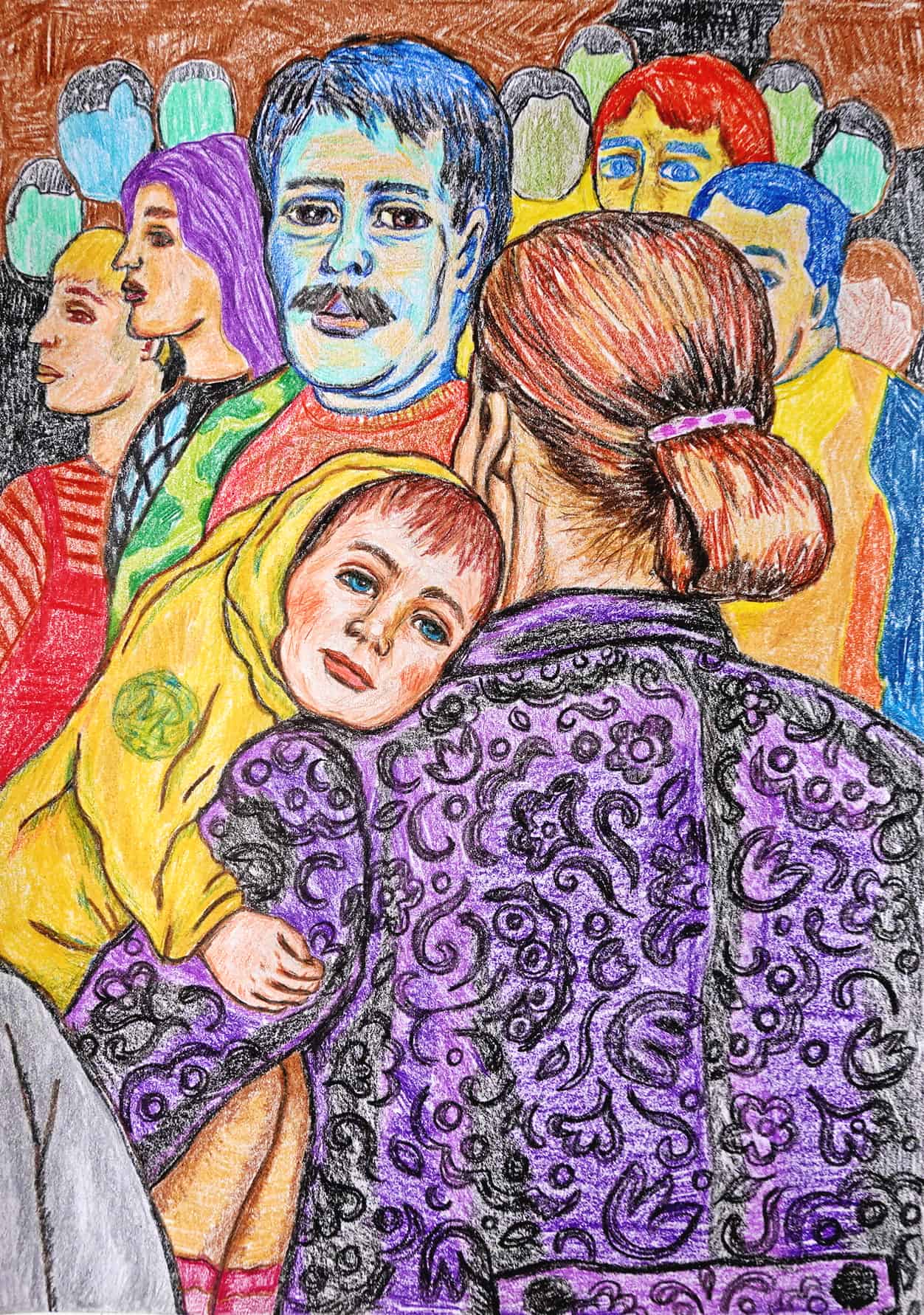

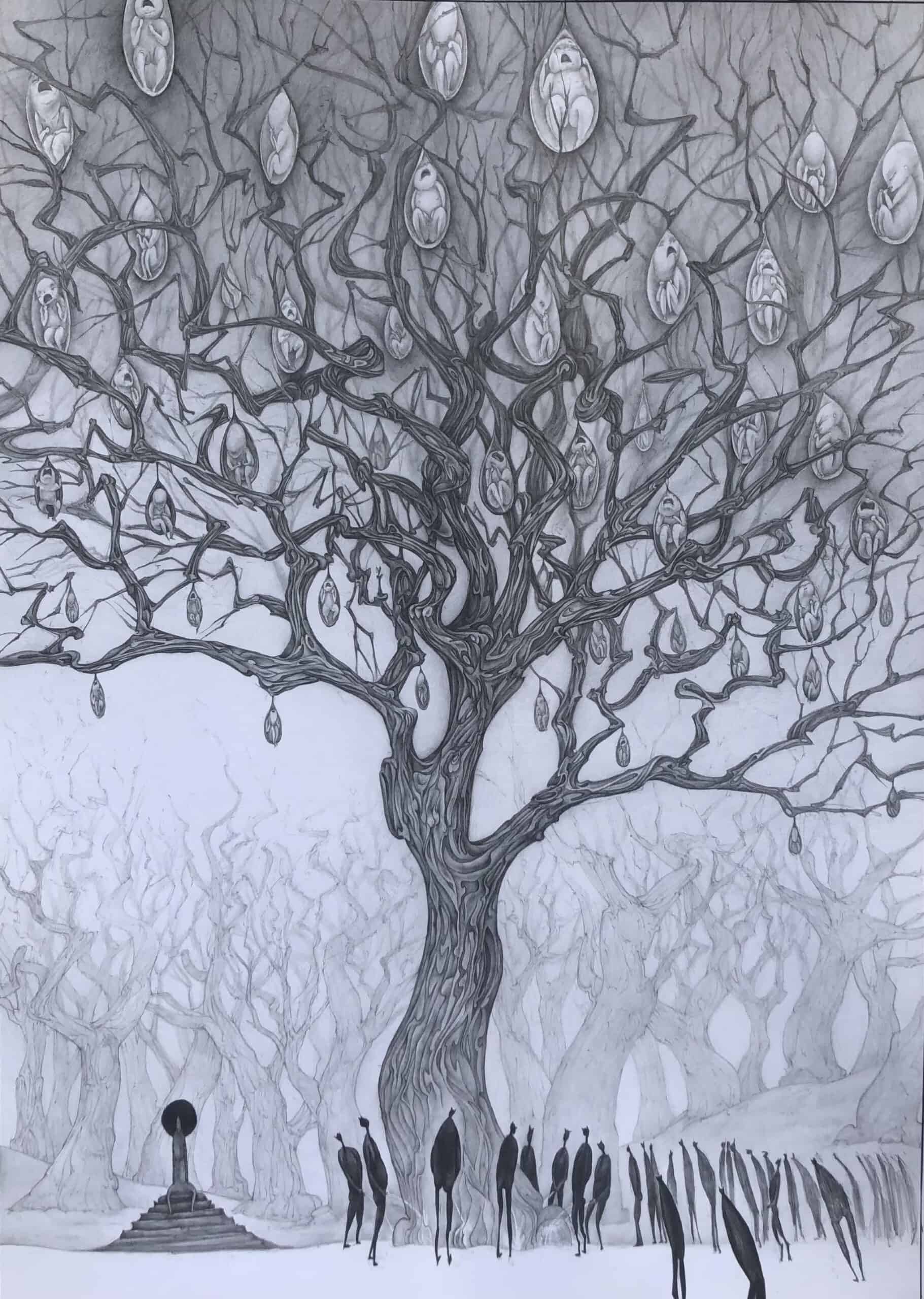

KOSTIANTYN TERESHCHENKO

Artist Kostiantyn Tereshchenko talks about his work: “When crowds are told to go kill, and they go and kill — the hair stands on end. I see several generations of morally crippled, inferior people living like dogs on chains. I see a state that has been leashing them since their childhood, a police state that incubates “freaks” to please the infernal will of the minority, disguising it under enlightened ideals and Russia’s Sonderweg. I see a family tree, under which the devils in power have been shitting and pissing for centuries, birthing the generations of the poisoned in the womb. It is how the nation is born. I saw it, and then I drew it.”

“The One Who Gave His Honor*, who is he without it? Is not it an immersion into the beastly layers of the psyche? And why do they give their honor so proudly? How do these people commit murder and violence and then report on the completed task to the leadership with pride? And then they write to their mothers: ‘Hi, mom, I am fine, though a little bit tired. They fed us well, today there was stew…’ Are they even human? If not, who are they? Seriously, who?”

*To give one’s honor refers to a “salute”.

LI BILETSKA

Li Biletska, a photographer, kept a sort of diary of the occupation routine on her Facebook page, and worked on The Women in the Occupation documentary. She made videos with the Residency participants and documented our underground meetings. The artist also created the Home Maria photographic series. The series incorporates portraits of women and girls in occupation and outlines a new wartime iconography.

“When friends ask me ‘how are you doing,’ I answer: ‘fine, we are holding up.’

Because I honestly do not know how to tell concisely:

that the mobile network and the Internet may disappear for several days;

that my wisdom tooth has been torturing me for several days, and there is no medicine in town, particularly painkillers.

that there are lots of checkpoints here;

that there are almost no residents on the spring streets;

that Russians brought ‘actors’ from Crimea at 2 a.m. for the fake Russian Victory March movie;

that the forest is burning and burning in the region. Russians do not put out the flames. Since yesterday, a veil of smoke has fallen on Kherson.

And it drags you down. But we are holding up. Stubbornly, we try to live. We still have to plant a new forest.”

“Today I have seen families having picnics in the courtyards of multi-story buildings. It was unusual. But it is delightful to see this pastoral of the occupation: improvised festive tables drowning in new grass; warmed by the spring sun, people are softening up, in a kind of calm contentment, with their children nearby. Beautiful.Or, maybe, I have projected my own joys while I was heading to my family’s meeting venue, because such opportunities are worth their weight in gold (to cross out).

Priceless.

Christ is risen! Ukraine will also rise!”

“It was a sharp reaction in the form of performance with a text full of incredible pain:

Bucha.

Pain.

Grief.

Devastation.

Burnout.

Rage.

Hatred.

The rest of the words become scarce and worthless.”

VOLODYMYR RAINHEARTH

On November 11, the Ukrainian Armed Forces entered Kherson. One can only imagine how people met them, how our flags flew all over the city at once. When Khersonites and our supporters around the world were celebrating this historical moment, BBC Ukraine reposted the animated artwork Time of the Watermelon Harvest by the comic writer Volodymyr Rainhearth and broadcast it all evening.

Watermelon became the trademark of the Kherson region, and its circulation reached almost a global scale, giving life to many memes and designs. It is hardly surprising that, on such a day, the media chose this image as a symbol of the indomitability of Khersonites. Well, we have reaped a rich harvest.

We published another artwork of Volodymyr, Attack of Watermelon Avengers, the next day, and dedicated it to the anticipated and inevitable liberation of the entire Kherson region.

The Residency project is ongoing. Some residents continue to create artworks related to the war in one way or another. Some take a break to settle in new places. The artists who lived through the occupation until November 11 experienced many emotions — from euphoria to complete emotional exhaustion. On top of it, living conditions remain extreme: the city still has no electricity, water, or centralized heating. There is an acute shortage of fuel and bread. But the providers are already setting up a mobile connection, and Khersonites can share news about life in the liberated city. Although the Residency is no longer “underground,” its activity does not end. We collect the works of the participants to continue the project.

All artworks are available on the Urban Re-Public Facebook page, which is constantly updated.

The Animation of Art Resistance in Occupation project is supported as a result of the (re)connection UA Open Call, a pilot project implemented by the MOCA NGO in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund.

The (re)connection UA aims at supporting the continuation of artistic creation and access to cultural life in Ukraine and values artists as essential actors in safeguarding Ukraine’s cultural diversity and identity and the role of cultural expressions for collective trauma healing, unity, and cohesion.