Defense Intelligence Operatives Memorial: a conversation with sculptor Nazar Bilyk

In June 2025, a memorial dedicated to fallen Ukrainian intelligence operatives was inaugurated on the grounds of the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (DIU) Directorate in Kyiv. It’s not a monument in the traditional sense, nor is it a public space. There are no heroic statues or war quotations here, only two white stelae that define the place of silence, commemoration, and personal reflection.

The memorial was designed by Nazar Bilyk, a Ukrainian sculptor renowned for his Pavlo Sheremet memorial sign, the Rain sculpture at Kyiv’s Landscape Alley, and the Sandarmokh memorial. DIU intentionally approached him with the request and provided a space for his potent artistic response.

In March 2025, Kateryna Semenyuk, a co-founder of the Past / Future / Art memory culture platform, visited Nazar Bilyk in his workshop to gain an insight into his work and discuss how the memorial was conceived and what it signifies.

This is an abridged and structured version of their conversation.

So, Nazar, how did it all begin? Who approached you, and what was their request?

The DIU people came and said they needed a memorial to honor the fallen intelligence operatives. Their only condition was that it looked like “anything but Soviet.”

I didn’t aim for a traditional, Soviet-like monumental sculpture anyway, even though my father is a sculptor, as is my grandfather, and monuments were all they discussed. I have long been avoiding that topic, preferring to develop a visual language of my own. Now I feel it’s fully formed, and I have something to say about memory.

“Anything but Soviet” is precisely what people ask for when they approach us. We have grown accustomed to this visual language, having been raised in it, and now we recognize it at first sight. But it no longer works. Societal demand for “anything but Soviet” is totally understandable. Knowing your previous works, they expected you to offer something contemporary.

They did. Their trust was what hooked me. They said, Nazar, figure out what it could be, make some draft designs, and let’s meet again in a month. And that’s what happened.

THE DIU PEOPLE CAME AND SAID THEY NEEDED A MEMORIAL TO HONOR THE FALLEN INTELLIGENCE OPERATIVES. THEIR ONLY CONDITION WAS TO ENSURE THERE IS NOTHING SOVIET ABOUT IT

Did you know each other? Or someone referred them to you?

They knew a lot about me. At the meeting, they mentioned my father, also a sculptor, who used to work with the intelligence.

You mean they didn’t even ask for your address? Just said, Nazar, we’ll be at your place in five? (laughs — editor’s note)

They came to my workshop, and we discussed everything there. I didn’t plunge into work, didn’t start right away. And then your team took me to Chernihiv.

Yes, we invited you on our Chernihiv expedition.

Getting two requests about the same topic in a row got the gears turning in my head.

I remember how we doubted whether you would go. We knew you had a lot on your plate. It was a great joy to see you arrive—having an experienced artist like you with us meant a great deal. Did the discussion part of the Memorialization Practices Lab help you?

It sure did. I checked out the participants’ capstone projects even when I was ill. The Lab provided immersion into the problem even at the idea development stage. Doing things alone is anything but easy, but there, I had a community.

In Chernihiv, I met Yehor Perepeliuk from Guess Line Architects. The bureau’s team and its founder, architect Andrii Lesiuk, made a strong impression. We made a great creative team, which gave me more confidence.

A month later, we held a presentation of three ideas for the future memorial. The following day, they called us back and said one of the ideas was a go. It was “evocative,” as they put it.

Which one did you like the most?

The one they picked, actually. It emerged at the confluence of architecture and sculpture during a discussion within our team.

Is this interdisciplinary aspect, when professions and languages are combined, a model for a good memorial?

I am accustomed to working solo and not particularly keen on teamwork, but the memorial called for a joint effort. Memorials are about working with space and multi-vector composition. That was the mindset I looked for in my potential partners.

And that synergy was there.

It was. We proposed a vision that focused more on the practice than on the object.

The thing about memory is that it doesn’t exist as such. It needs a practice of some sort to exist. It must be created and sustained, which takes effort, and putting in effort is a choice. Our project includes this kind of practice. Today, we stood at the memorial and thought about how it could be interacted with.

Yes, we thought about how people would enter that space, what they would do there, and how they would feel.

The two stelae cover you like hands or wings, cutting out the noise and evoking a sense of protection. There, you can be near those who are no longer with us, but still close, through memory.

As it happens, there is a certain rhythm of life at that place—everybody is hurrying somewhere. It’s the intelligence directorate, after all. The memorial offers an alternative of sorts: to escape that stream and transition to a different state. And it happens so fast. The feeling changes the moment you enter the space between the stelae. Technically, everything stays the same, but something clicks inside you.

The idea was to create an inclusive space—an open environment that functions as a mini-park. The memorial would become a place for a range of emotional experiences from grief through closeness and to a particular kind of recreational recharging. A space for rethinking.

We filled it with greenery and thoughtfully approached setting the route that people would take through the memorial.

THE MEMORIAL WOULD BECOME A PLACE FOR A RANGE OF EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCES FROM GRIEF THROUGH CLOSENESS AND TO A PARTICULAR KIND OF RECREATIONAL RECHARGING. A SPACE FOR RETHINKING

How did you come up with the visual language, and what was the meaning you wanted to impart?

I realized that working with intelligence took talking the same language—the language of symbols, signs, and ciphers. We wanted to integrate this language into the memorial.

When they saw the memorial’s top-down visualization, they found it moving. It’s impossible to notice as you stand near it. But from a bird’s-eye view, which you would see on Google Maps or satellite imagery, it looks like an eye watching the stars from the Earth— unsleeping, unblinking. This is the main idea behind it.

DIU’s motto is Sapiens dominabitur astris, and the memorial will light up in the evening, like a starry sky.

Also, the wings, flame, and shields are all metaphors for their land, air, and sea operations.

The symbolism of DIU’s emblem—the owl—is also there. The eye, the wings… There are many layers of meaning here. And they caught it all. Even though it’s not a literal depiction or a direct reference, they recognized themselves in that complex form and multi-layer approach.

They did. I saw that recognition happen.

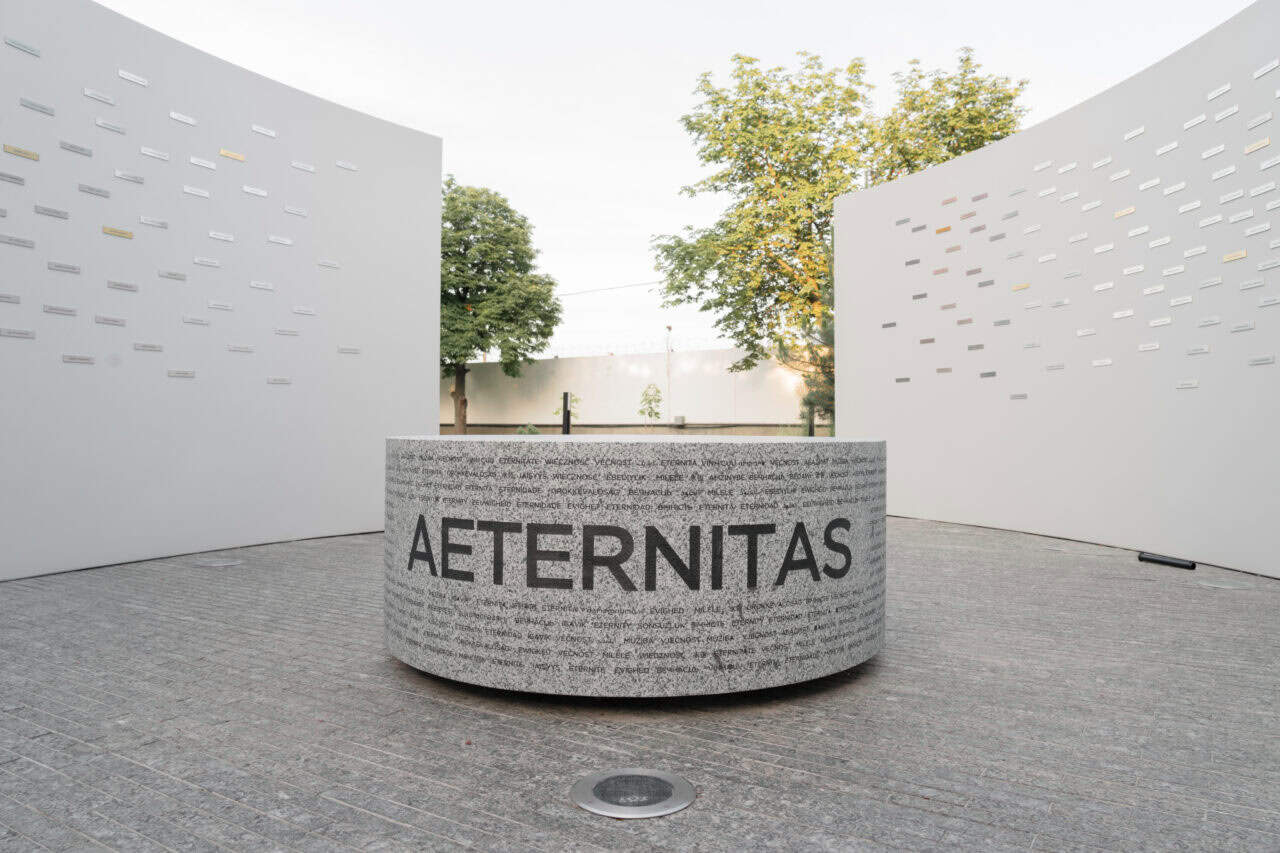

Specifically, it was when we discussed the memorial’s central element—the round platform between the stelae. It looks like a pupil of an eye. It was conceived as a place to put flowers, death lanterns, or other tokens of respect.

On its side, we put the word “eternity” in different languages.

You said it was the only thing that Kyrylo Budanov (Chief of Main Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine—translator’s note) had a specific request about.

Yes, he said it would be great to thank all our partners from many countries globally.

And we decided to write the word “eternity” in the languages of all those people who work with DIU, accenting the Latin one—aeternitas. This is our way of expressing gratitude through language.

They told me that many foreigners work in DIU units, so it’s an important thing to do.

And then there are the names on the inside of the wing stelae…

Yes, we wanted to honor each of the fallen with a dedicated plaque. Initially, we considered engraving. Later, though, we got the idea to make chevron plaques with names or even call signs, mimicking their counterparts on uniforms. It’s the military’s visual language distilled into a modest stainless steel plaque.

How many plaques are there? And why are they arranged like that?

The composition is akin to an explosion: denser in the center, and sparser toward the edges. This structure is also meaningful. So far, we have made about 500 plaques. But more can be added, and, unfortunately, we will have to. The form provides for it: I laid down the composition so that it can be scaled up to 1,500 plaques later. Among those names are dozens of Heroes of Ukraine. Their plaques stand out because of their color—they are golden instead of steel.

Do you indicate ranks, years, or call signs?

No, just full names without patronymics, because some of them are foreigners. The names of foreigners are written in the Latin script, while those of Ukrainians are in Cyrillic.

How did you pick the material for the stelae?

We took our time with that decision. Stone wasn’t the right fit in our view, and bronze felt too heavy and traditional. And then we got an idea to make it out of fiberglass. After all, it’s the material that DIU units work with. Drones, boats, and even missile bodies are made from it. We opted for thicker walls and light-gray paint—that’s the color of most drones.

IT’S THE MATERIAL THAT DIU UNITS WORK WITH. DRONES, BOATS, AND EVEN MISSILE BODIES ARE MADE FROM IT

Also, it’s a really cost-effective and durable solution.

It is. And it’s symbolic and optimal, too. The stelae have a metal framework inside, which is integrated into their foundation. It‘s the engineers’ work. I won’t deny, I’m nervous about it, and I will be until it’s installed—that’s when everything comes together.

If installed this summer, it will make around a year from the project’s idea to execution. That’s fast.

It’s really fast. It takes people a year to renovate their apartment, and we will have built a memorial in that time. I mean not the stelae themselves but also the landscaping, lighting, and greenery. Even for a footprint this small, a year is really fast.

The next step is to see how people interact with the memorial, how they react, and how it works.

In February, we had a groundbreaking ceremony, inaugurating the memorial’s first element on the anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. I was privileged to talk after Budanov. Then there were floral offerings, and the music… And although we all got somewhat used to the emotions and the funerals, it brought tears to my eyes. And I had an even more profound realization of what we do, for whom, and why.

This is the state you want to end your work in and see how people take it.

As a professional community, we all look forward to the completion of your DIU project. It would be a great example of how a contemporary memorial may look. We are often asked for “anything but Soviet,” but what are we to show? The Vietnam Memorial in Washington? It’s a different country and a different war. And this one will be here, and it’s Ukrainian. Although the memorial is located in a restricted area, its significance is hard to overstate. Will it be accessible to the public, by the way?

Sure thing. It will be open to the public on some dates. The territory is gorgeous, with all the grass and water.

I doubt it would become the top dog walking destination. (laughs—editor’s note) However, it’s great to have an opportunity to visit it.