How Modern Art Works with the Theme of Hunger

For the Day of Remembrance of Holodomors Victims in Ukraine, read about how artistic practices help to work with the traumatic past and about the experiences of other countries that have also lived through periods of famine.

Ukraine

Memory is passed down through generations, coming into life through family habits that we begin to understand only as we grow up. Ukrainian artists Lia Dostlieva and Andrii Dostliev asked themselves, why are they ashamed to throw away food — it’s just leftovers on a plate? And they answered to themselves that Grandma used to tell them stories about Holodomor.

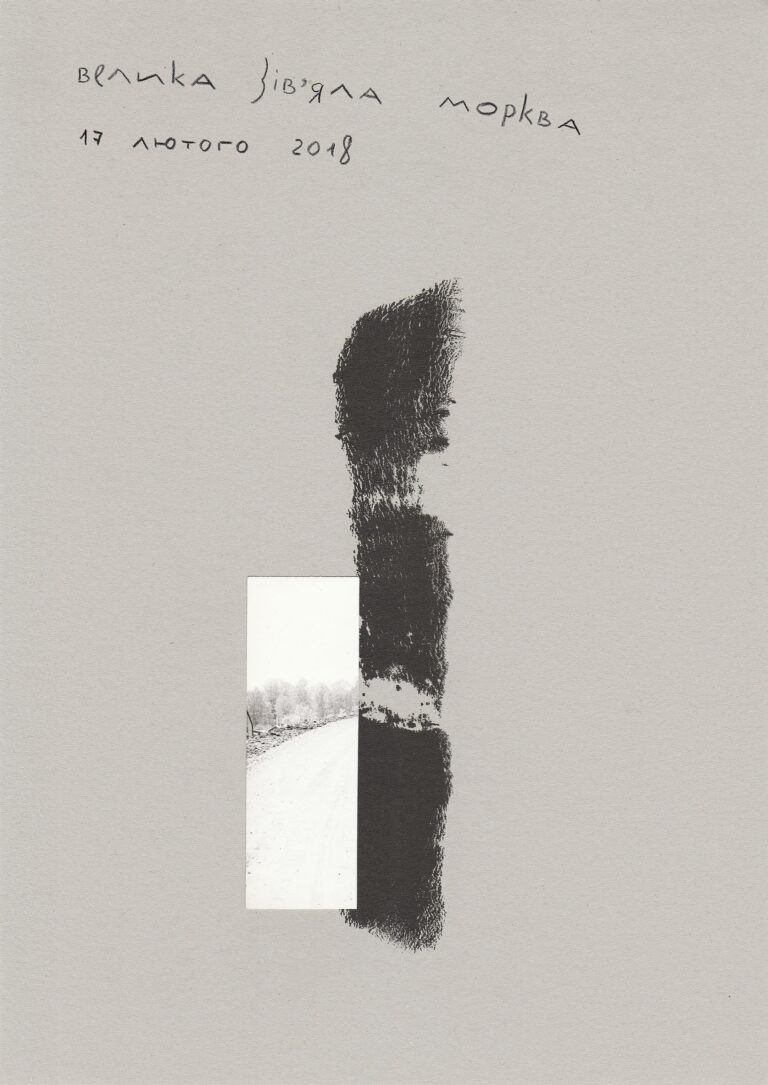

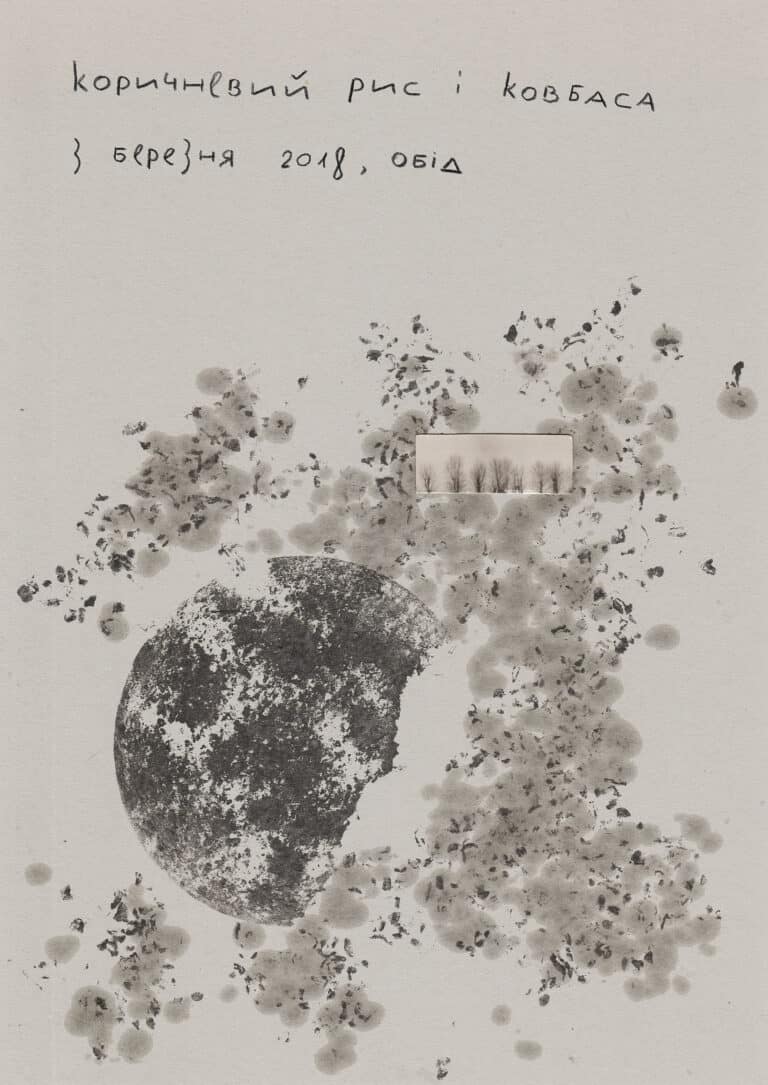

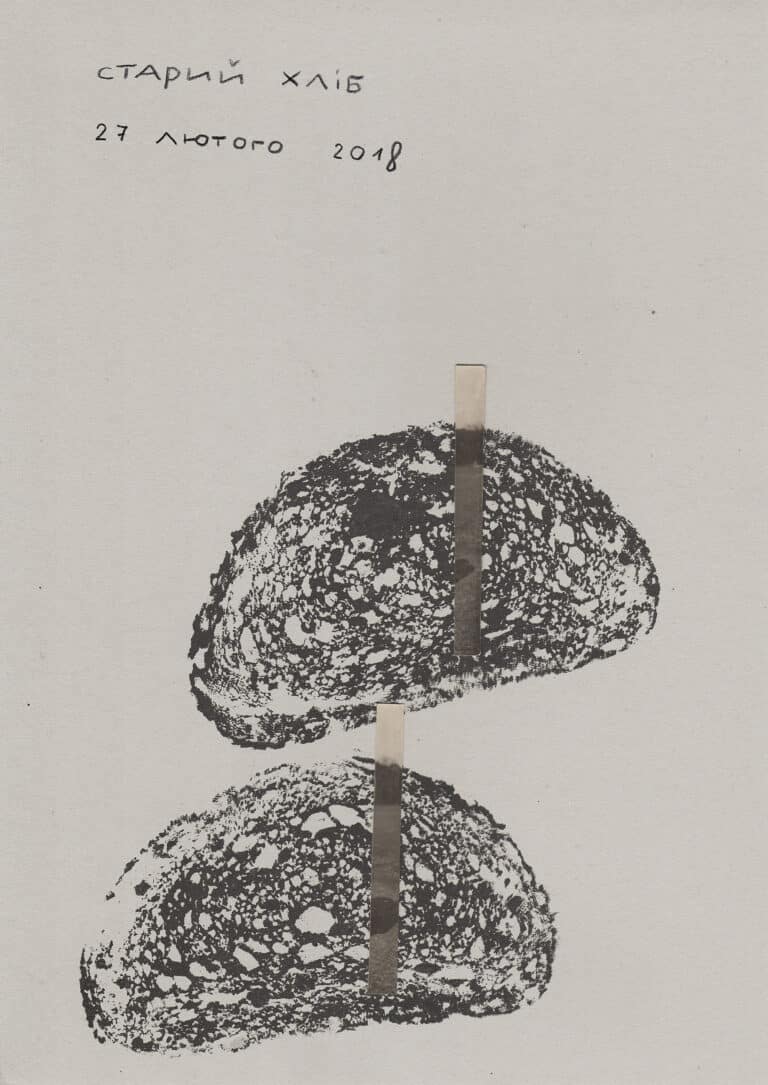

Their project, “I still feel sorry when I throw away food. Grandma used to tell me stories about Holodomor”, is not devoted to the actual event, but to memories of the horror, which live in our everyday habits, fears, thoughts. Artists spent two months conducting visual research using post-photographic practices, recording traces of leftover food. These traces, along with Ukrainian landscapes, became parts of collages.

These images can be seen as a quote from the Austrian researcher Martin Pollack, who wrote the famous book “Contaminated Landscapes”. Sites of mass crimes are now hidden among the beautiful landscapes that become “contaminated” when we learn about what has happened here.

With surprise the artists realised that the famine left traces in our memory, but left no trace in the physical space of Ukraine. The authors do not try to represent a terrible event; they try to understand how to live with its memory, overcome fears, without forgetting anything.

Serhiy Zhadan reflected about the project: “We are all united by this flow, we are all connected by a shared memory, which we try to live with, which we learn not to be afraid of, which we try to love. The last may be the most difficult to accept. But sometimes it is possible”.

Kazakhstan

As in Ukraine, 1932–1933 in Kazakhstan was marked by tragedy. Asharshylyk is how famine sounds in the Kazakh language. The forced transition from nomadism to sedentarism, collectivisation, and Stalinist repressions claimed the lives of 1.5 million Kazakhs. Hundreds of thousands were forced to leave their homes searching for a better life.

Artist Saule Suleimenova addresses this and other dark pages of Kazakhstan’s history in the project “Residual memory”. It was based on archival photographs. The work “Asharshylyk / Famine, 1932” became one of the first in the series: tired people with packages are walking to escape from hunger. “This road is famous. People went to China and Afghanistan, and it was all strewn with bodies. I was looking for the right mood to work with this subject: no fury, no anger, no offence… Even pain can be cleansing and beautiful. I was looking for balance”, the artist said in a conversation with Past / Future / Art.

The technique of “cellophane painting”, which has already become a signature style of the artist, helped find that balance. The project consists of collages made of multi-colour plastic bags on a grey film made of recycled polyethene.

“Residual memory is the one we try to hide, and I pull it out”, explains the artist.

Talking about such traumas as Asharshylyk, this method is exceedingly contrasting. The artist chose packages from a cafe, chocolate wrappers, tea, bread wrappers—all in warm tones and colours of sepia, which remind us of old photos. We can interpret it in different ways: on the one hand, it is a matter of combining visual images of different times; on the other hand, it is a question of facing the modern world with its culture of consumption and the past with all its tragedies. It is crucial for the artist to maintain the cycle of life, where even the products of human existence have a purpose and speak to the ancestors. In this case — metaphorically to feed them, to pay tribute and get support.

For Saule Suleimenova, the painful memory of the past helps not to abandon this past but to let it end and to finally open the way for today. “The topic of the famine is deeply embedded in our subconscious, even if it was not in our generation or our parents’ one. I still can’t watch a movie in which someone plays with food, for example when people are throwing cakes. The memory of those horrific times came up implicitly. There was no way our grandparents would sit down and talk about it. There was some kind of a ban. Now it’s important to get it out of our system, accept it, and come to terms with it. Traumas should not be hidden”, says the artist.

You can also read about the work with memory and Kazakh history of the USSR times in the text: “Hacking Lenin: Fate of Soviet Monuments in Kazakhstan”.

Ireland

Our next stop is Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University in Connecticut, USA.

The famine occurred in Ireland from 1845 to 1849 and had several causes: on the one hand, there was the ill-conceived economic policy in the UK, part of which Ireland was at the time, and on the other hand, the epidemic of a potato disease, the peasants’ primary staple (which is why this event is sometimes called the Irish Potato Famine). Up to 1.5 million Irish people died, and the same amount emigrated. Overall, the population declined by almost a quarter.

These events are still part of the collective memory of Irish people in different countries. The American Irish created a museum to stimulate reflection and inspire the imagination to reflect on such a complex subject.

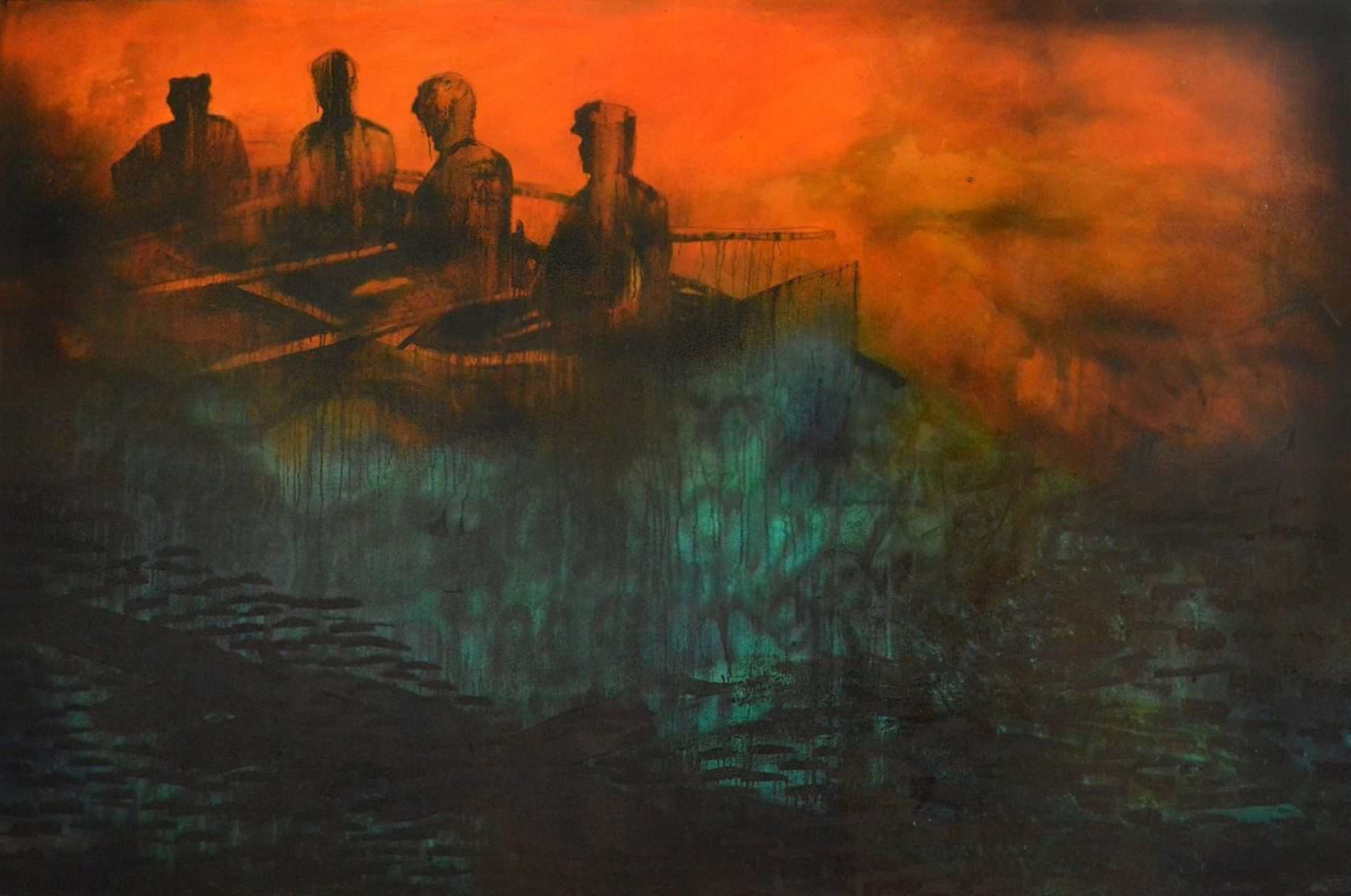

The museum’s collection includes paintings by influential 19th-century artists and contemporary Irish artists. And if «classical» artwork documents hunger and its consequences, the works of authors of the 20 and 21 centuries, made in different techniques, invite us to reflect in different directions.

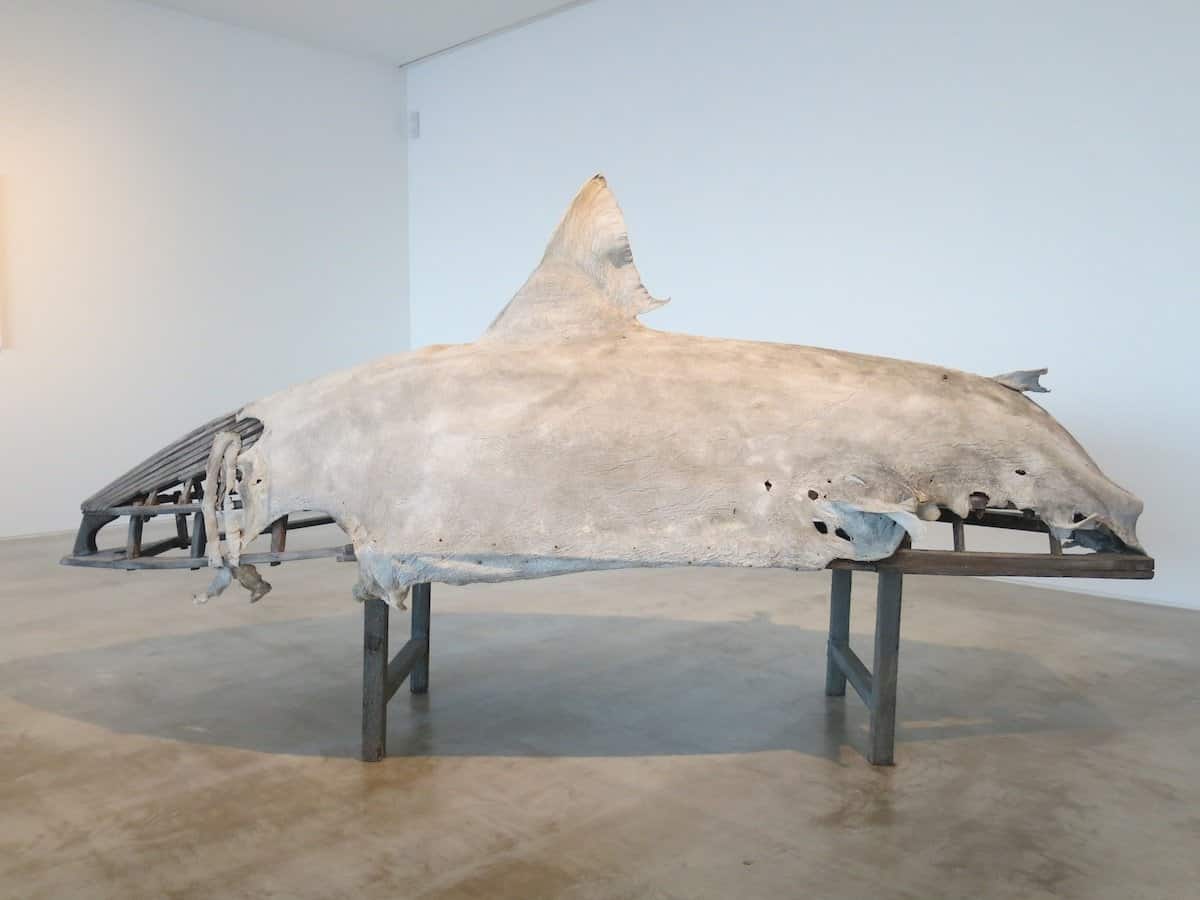

The artist Dorothy Cross stretches the traditional Irish boat currach with the non-traditional skin of a basking shark instead of the usual cowhide. The question is often asked why did people starve when Ireland is surrounded by the ocean. This work resonates with an evil irony: when the potato harvest failed, those fortunate enough to own a currach had to pawn or sell their equipment to buy food.

An anthropologist and artist Toma McCullim asked the employees and patients of the hospital, which is on the site of a former workhouse for girls, to make spoons from wax. During the famine, young female workers were sent to Australia, where there was a shortage of female workers. A spoon is one of the few things they were given on their journey. In 2018, 110 wax spoons were cast in bronze in memory of 110 girls who crossed the ocean. The project is named after one of them, Jane Leary.

Joe Hogan, A Famine Memorial, 2011, mixed media

Toma McCullim, Lane Leary, 2018, bonze on bricks

From Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum’s collection, USA

Joe Hogan has a degree in philosophy, and he likes two things: nature and baskets. He likes making baskets out of natural materials. Slowly, without rush, thinking about the place and its connection to people and the current moment. One day he decided that from now on, he would make non-functional art baskets. The museum stores Hogan’s work “A Famine Memoria”. It is a peculiar dedication to the traditional Irish basket used as a colander for boiled potatoes and a serving dish. “I look across at the traces of potato beds dug by spade more than 150 years ago and wonder about the people who lived here then and the suffering that was endured in the great famine”, says the artist.

For more works, visit the website of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum.

Title photo from Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, USA