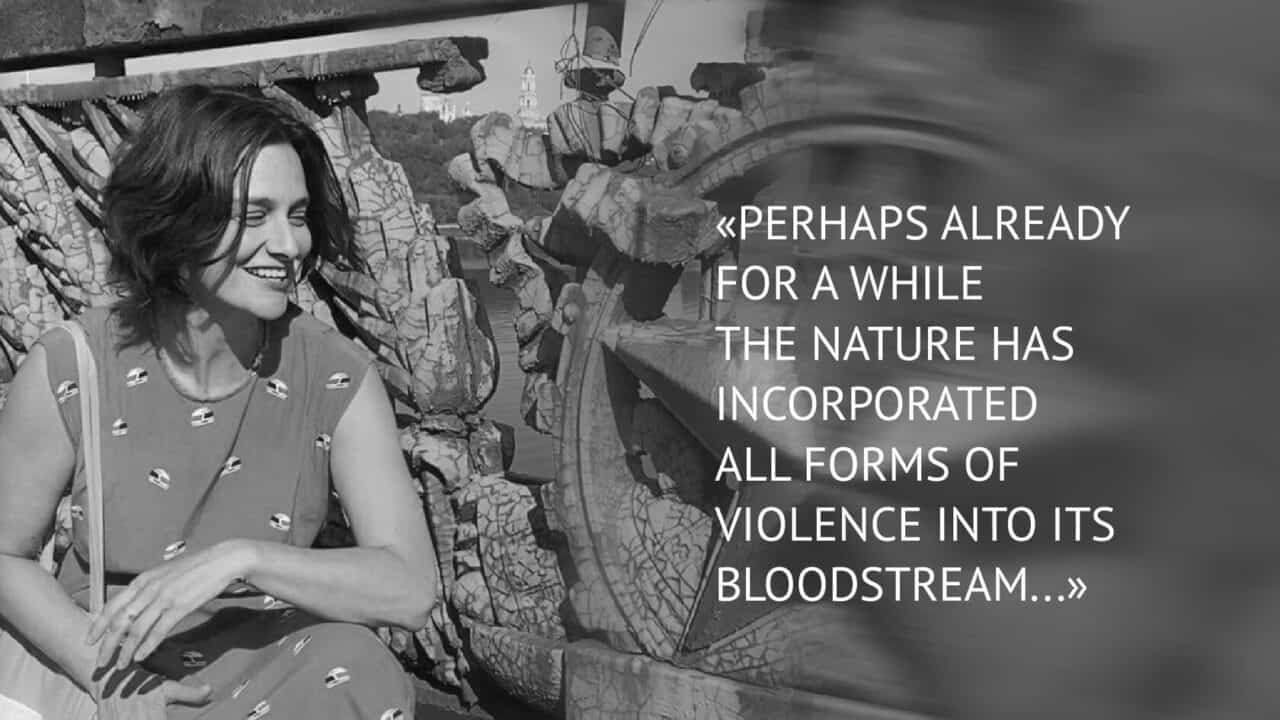

THE WALK THROUGH THE PLACE, CALLED BABYN YAR: A CONVERSATION ABOUT MEMORY WITH THE WRITER KATJA PETROWSKAJA

Within the program of events on the Holocaust commemoration, the curators of Past / Future / Art Oksana Dovgopolova and Kateryna Semenyuk talked with the writer Katja Petrowskaja about her book Maybe Esther, accommodating the tragic past through becoming mute, the pursuit of a new language, Kyiv memories, and people, foregrounding the novel. We are publishing the discussion’s fragment, the complete record is available via the link.

Text: Past / Future / Art

Katja Petrowskaja is a writer and journalist, laureate of the Ingeborg Bachmann literary prize. She was born in Kyiv in 1970 and has been living in Berlin since 1999. She is the author of “Maybe Esther: A Family Story” (Vielleicht Esther) — a novel-reflection on the nature of memory and the human relation to the complex past. In Ukraine the book was published in 2015 by the publishing house “Books – XXI” in the translation by Yuriy Prokhasko.

Does Memory Sprout? is an international program on the Holocaust tragedy commemoration. The project took place in Ukraine and Poland from 13 August to 30 September 2021. It included the art & science exhibition and public discussions. The project was implemented in partnership with forumZFD, the Ukrainian Institute, and the Laznia Centre for Contemporary Art.

THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF THE PLACE AND THE ABSENCE OF “STRANGERS”

Oksana Dovgopolova: This book illuminates the relationships with memory the modern human enters through questioning the significance of touching something in the past. I will start from the quotation on how we live inside the memory:

“Many years ago I asked one of my friends, David, who always visited Babyn Yar on that day, if his relatives lied there. He said it was the silliest question he had ever heard. Only now I understand what he meant. It does not matter who you are or whether you are mourning your dead — or, maybe, he longed for this insignificance? — for him, it was a question of decency. I would like to narrate this walk as if it was possible to omit that my relatives were murdered there, as if I was capable of being an abstract person, a person-in-themselves, and not an offspring of the Jewish people, tied to them merely with a pursuit of absent tombstones. If it was possible to be that person and to stroll around the eerie place called Babyn Yar. Babyn Yar is a part of my history, and I was granted with nothing else; nevertheless, I am here not because of that or not only because of that. Something leads me here as I am certain there are no strangers among the casualties. Everyone has someone here.”

Katja, you mentioned that now you understand what he implied. What is these optics for you?

Katja Petrowskaja: You speak about memory, however, for me, it is all about the life of the human among other humans. David is my father’s friend who went to the USA in 1974-75. He was not allowed to live and work. He is an artist, a person born at the end of the 1930s in the town of Chornobyl. If you visit Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, you will see the inscription “Chornobyl” on one of the first stones. For me, it was a revelation that Chornobyl used to be a Jewish town. Years passed as I understood that one of the reasons behind David’s departure from Kyiv was not only the impossibility to find a job and antisemitism of the 1970s but also the forbiddance to visit this place, Babyn Yar.

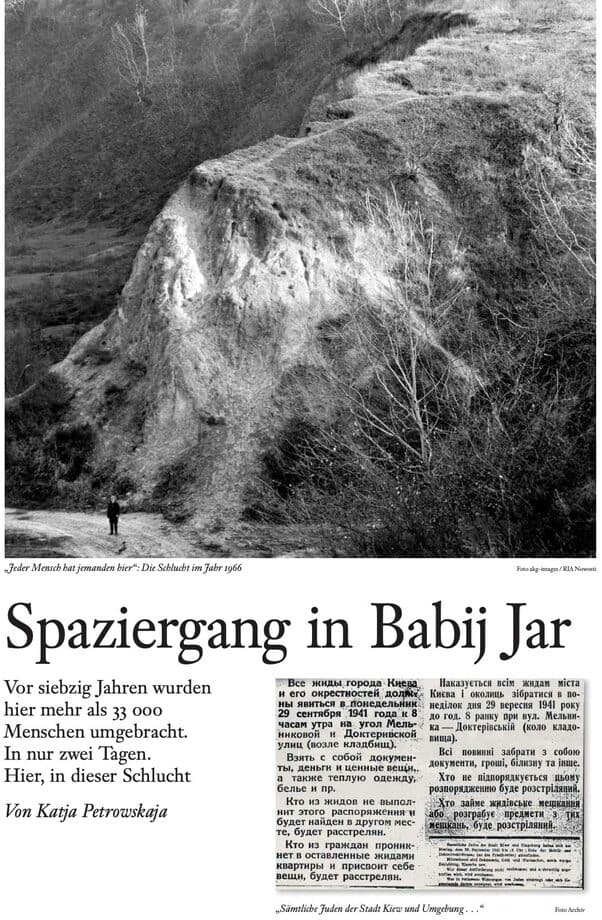

Imagine, a person approaches the stone, installed 25 years after the murder of nearly 100 thousand. They visit the stone to put flowers and receive a 15-day arrest for littering. Those are the things we have difficulties comprehending — the register the people lived in, what they withheld and what they articulated. Hence, when we now pondering the third generation, the memory’s memory, I do not understand the subject of our discussion completely.

Since early childhood, I have been experiencing the feeling of extreme acuity, the infeasibility of the place, because I was in touch with the people who were banned from visiting the site. I went to Babyn Yar with my parents, and it was also an urban experience. There was no subway; thus, we took a trolleybus to St. Cyril’s Church. First, we entered the church and contemplated the 12th-century frescoes where an angel unwraps or wraps the sky or Vrubel’s fresco The Descent of Holy Spirit on the Apostles where the apostles were depicted after the Pavlov’s asylum patients. Babyn Yar truly begins from the latter. They were the first to be killed at the site. Afterward, my parents and I walked on the tiled road where people were strolling and children were playing — later, it turned into some kind of a sports ground. It was an odd route to the Soviet monument that did not mention the death of Jews at all.

It is not about memory as much as about experiencing the space: is it possible to live in the city where the thing transpired, but everyone is silent? That was in my childhood. Later, everything changed several times. The separate subject is the contemporary events in Babyn Yar. Perhaps, the silence was better.

In 1961, Hryhorii Synytsia painted an artwork that responds to the question about David. The reproduction stood inside my father’s bookshelf. I did not realize immediately what was portrayed there. Hryhorii Synytsia is an absolutely wonderful artist-monumentalist, the creator of phytomosaics. He painted this artwork titled Babyn Yar. Prior to 1961, there was not any monument there.

The question of the great importance of whether the painting was created before or after the Kurenivka mudslide. The latter activated the memory of other casualties as the situation of “non-memory” of particular victims revealed others. It is well-known that the Soviet government built factories that pumped the pulp dump, the dam collapsed and unleashed on the Kurenivka.

This painting remained inside the father’s bookshelf for a whole life. It depicts a ravine and the white-stone city at its edge. I do not know how memory truly operates, but peculiar things imprint on your mind and produce distinct perception matrices. The matter does not concern the memory of Babyn Yar directly; it alters the way you watch the news, you react to the atrocities, experienced by others. Once, I was impressed with Varlam Shalamov’s statement: “It is all about the person’s behaviour in the crowd.” It is about that insomuch as about other definitions.

Impressive protests were held at Babyn Yar, followed by the monument’s installment. There were brilliant people, for instance, just imagine a handsome lad named Emanuel Diamant. He, jointly with several other people, initiated the protest in 1966 on Yom Kippur, the 24th of September. On the 29th of September, they organized a massive rally with Viktor Nekrasov and others. Ivan Dzuiba’s speech, articulated at the protest, is still one of the most up-to-date texts. It was a spontaneous gathering of the decent people who did not want to live in the city where Babyn Yar was not vocalized. Their words are sharp and astute. We cannot even imagine the first-handedness of the tragedy’s sense those people bore.

The voice I was looking for was meant to address them and the feeling of the absolute impossibility of the site within the city via questioning how it was feasible to live in the city or perceive the site.

Oksana Dovgopolova: Precisely, I read this statement as a thought on the people who visited the site during the times of the ban, when the mere visit led to dire consequences. Ivan Dzuiba’s speech is a text that I constantly quote. For me, it is essential to see this dimension of Babyn Yar’s history as an indispensable part of the tragedy’s commemoration. When we remember the people who came here to stand up for the decency of those who lost lives there, it is something we cannot select out, put on another shelf. It is embedded in our lives now. Probably, this is why we perceive the word “memory” differently. Memory is a framework we live in now. It is not about the past, it is about the present.

Katja Petrowskaja: I actively resist the transformation of “memory” into the term. We use this word repeatedly, it emasculates. I insist on German “Wahrnehmen,” which conveys something close to “peception.” The perception destroys time, forcing a person with their bodies to enter the center of the picture. Memory is something in the head.

For me, David’s statement highlighted that, regardless of who you are, you are capable of sensing another person’s pain or just another person. Actually, that was what he said to me: it is not significant what prompted him to bring flowers to the site or visit it. And it was astounding. Because we always talk about the Ukrainians, the Jews, the Russians, etc., ruining with this national identity the perspective where it does not matter.

Astonishingly, the people with both Jewish and Ukrainian identities were together at Babyn Yar in 1966, and it is crucial. Usually, the fact it was Hrushevsky’s birthday anniversary is forgotten. Moreover, it was a jubilee. Impressive. It is precisely about the possibility of the people’s unity in their city amidst the tragedy’s sense, urging to be addressed. I think such things are gone for a long time. They remain in some people, in some initiatives; however, this simple thing of “we have to live with it in our city” is not about some strangers. I suggest David were willing to tell me that there are no others when the city is yours.

Oksana Dovgopolova: We are exactly on it: the potential of different people to unite to see others’ dignity and protect it. And it does not have to be a hypothetical “one of their own.” An appeal to this part of the Babyn’s Yar history is the most vital aspect that is absent now. We can bring it forth today if we actualize it, remember it, and incorporate it into our lives.

“When Ukraine became independent 20 years ago, each victims’ groups received their monuments: a wooden cross to the Ukrainian nationalist, a monument to ostarbeiters, statues to two member’s of religious resistance, a plague to the Romani people. Ten monuments but no shared commemoration. Even in the memory this selection persists. We lack the word “human.”

When we work with the past, we face two traps where you can be easily captured. On the one hand, there is a trap of the tremendous numbers where you can say and be petrified by the number of people murdered on-site. It loses a separate individual. As this Soviet monument epitomizes, there are symbolic figures but no living ones. On the other hand, there is another trap when we try to follow private recollections and address a particular person. Inevitably, we attempt to describe this person, but we do not have a language to move beyond simplifications: they were the Jewish, the Romani, prisoners of war, etc. When we start to thread the definition, the selection occurs with enlisting a plethora of small groups and omitting the specific person. When we say, “Let’s address a human,” the response we receive is, “Oh, you want to universalize, you want to make a monument to the Soviet people again, neglecting the fact that there were diverse groups.” Nevertheless, there was a moment when it truly did not matter who was “of our kind” because it was an issue of decency.

THE SEARCH OF THE LANGUAGE AND THE URGE TO BECOME MUTE

Oksana Dovgopolova: As we have tackled the diverse groups who visited the site and discovered common grounds, we can elaborate the subject of the different languages, not in a narrow sense German, Russian, Ukraine, but in more general terms — the semiotic systems. When we speak about working through memory, we are in relentless search of the language. While I was reading Maybe Esther, I had an impression that the experience of residing in-between the languages is a separate subject of the book, your experience.

The book was written in German, and it was a conscious gesture. The language of the deaf appears in the text as the language your relatives taught children. There is a сertain act of overturning the subject of the sign language through the German-Russian author’s narration of her pursue in tracing Yiddish- and Polish-speaking forebears. As you write: “Poland was deaf, I was mute.” It is a permanent residing in the in-between space where new senses are produced. Was it essential for you?

Katja Petrowskaja: I think if I were not an emigrant, I would not write this book. I came to Berlin out of love for the city, and the memory of the war activated simply because you walk these streets. I arrived in Berlin when the Wall had just fallen. In the eastern regions, the side of the Soviet army advance was still apparent. I was shocked. I saw a “hole” in the Berlin capital, called Potsdamer Platz. Before the war, it was the largest transport interchange in Europe, there was the first traffic light in Europe, and so on, and in the 1990s the area remained a ruined space.

The Wall preserved the war vestiges, and, consequently, a person came to the city where World War II had just ended. I was enormously impressed by that. I think that everything connected with Kyiv and the feeling of war incredibly intensified through the German language because it became possible for me to fall in love with the German language. Who would tell me …

The things I consider impossible began to develop. Perhaps, the inability to convert our stories, either emotionally or verbally, into some other space facilitated the process. Similar to a photographic effect — the film, in fact, is developed in an alien environment.

This is what happens with the childhood experiences and the space where you grew up — you need some shift. It was launched with it. But why have I written in German? It is partly intuitive, partly because all my friends spoke German, no matter were they German or not. It was the language of communication, and l wanted to employ that. It did not originate from the idea “now I will write about this subject.” The book emerged, of course, from an oral narration; I think it is conspicuous. One of the Ukrainian reviewers mentions: “It feels like the author wanted to stop me in the park and tell her story instantly.” It is the smartest thing that has ever been said about my book.

The book is not about Babyn Yar as much as it is about our contemporary who stumbles through all these catastrophes of the 20th century when they travel across Europe, when they travel by train from Kyiv to Berlin, to Austria, Poland and etc. It is a sense of space where you taste the gifts of modern European life while constantly stumbling because of some terrible things, some failures. It is enough to pass through the forests of Poland, where hundreds of thousands of people died — the first mass killing was in Chełmno, 300 thousand people. Here is this feeling: I do not know how to talk about it and how to preserve the memory, to preserve the story of something and not destroy yourself or others with your storytelling, because the story of violence repeats violence.

Kyiv, Public Media Academy Studio

Maybe, it all started with my parents because what they thought was absolutely necessary to share turned out to be something I was not ready for. But they were just a generation of people who had an urge to tell. The Holocaust was not the most crucial topic. Stalin’s repressions, the suppression of the Prague Spring, and Afghanistan, the subjects not discussed in the Soviet Union, were essential. My parents considered it a personal necessity and freedom to talk about it. They unload themselves from Soviet lies with these stories.

I remember well how I asked my father — I was 11 years old — why Mayakovsky committed suicide. And my dad decided to tell me everything. And I remember the moment when this knowledge was unleashed, and I cannot stand it as an 11-year-old child. A simple pedagogical question— when and how? — might be the most critical thing in general. How to pass this knowledge without destroying the child’s soul? Or human’s one.

The institutional memory, planted in Germany, on the one hand, is a vital thing. Racist remarks are impossible for the state or a person in their public life. On the other hand, it is not to be decided from within. And I, for example, do not understand why children in German schools first read The Diary of Anne Frank and then Schiller.

When I was looking for a way to narrate, all of it was important. But, probably, the most intuitive finding was the feeling that you need to become mute foremostly. I was looking for a moment of material resistance. It is infeasible to talk about these things in any stream, and my German, although it exists, is obstructed. It was an attempt to make one’s own language difficult, that is, to become mute at first, acquire language through savage resistance, speak about losses while being deprived of the mother tongue.

Oksana Dovgopolova: To acknowledge that “I do not know how to talk about it” is the essential question of how to talk about something terrible and not mutilate another, not to maim oneself. It is about the urge to be silent at first, to enter the space of silence.

When we talk about the commemoration of Babyn Yar, the word “silence” always comes up. To recall Viktor Nekrasov, in his article on the competition for the monument design at Babyn Yar, he put a wonderful phrase: “Do not yell at me!” Indeed, there are eloquent projects that cause a storm of emotions, but please, do not yell at me because I came here to be alone with people who are gone, in the privacy of my mind, and not in the yelling space. In 1966, Ivan Dziuba precisely started his speech with the statement that it should have been a place of silence. But silence is possible where everything has already been said, where everything has already been articulated. And nothing has been enunciated here.

DOES NATURE GO INSANE?

Oksana Dovgopolova: I propose to move towards Martin Pollak, whose book Tainted Landscapes has been popular in Ukraine recently. The book is on how murderers become gardeners, and in the places of mass crime, we see forests, beautiful landscapes that draw us into their beauty. But once we find out what happened here, this landscape will never be as enchanting to us as it used to be. What do these tainted landscapes mean to you? Do you consider these optics relevant in the case of Babyn Yar and, in general, for the places where something terrible happened?

Katja Petrowskaja: I do not like this term particularly, and I do not really understand why it is so popular now. I know and respect Martin Pollack, but it is an odd idea that those who were killed actually contaminated the landscapes with their bodies, and we cannot enjoy them now. Besides, this concept implies that there is a therapy, a method, a ritual that can aid us to overcome these wretched places and wander pleasantly in the woods.

Kyiv, Public Media Academy Studio

I was once struck by a man, the son of Third Reich director Veit Harlan. Veit Harlan created the infamous film Jud Süß, which was shown to all Auschwitz wardens so that they could do what they did. His son went insane literally because of such a father figure. After the war, he set the cinemas where Harlan’s films ran on fire. He believed his father should be convicted, but the court acquitted him. Harlan’s son was one of the first people to visit the Polish forests on their own in the late 1950s. He went to Chełmno, where the first massacre of World War II took place.

For me, it was the first encounter with the idea of a landscape or scenery in literature in such a rigid form. He wrote one novel — it is not a historical story. It is something where the language just falls apart, it is not clear what is going on. But there are incredible passages in the text on how nature should have gone crazy. The need for this man to believe that nature has gone mad from this crime is somehow closer to me than Pollack’s terminology.

The forest of Babyn Yar, the trees we behold now, is a truly remarkable landscape. For me, this walk was like a journey in the movie Blow-Up by Antonioni, when a person uncovers a crime, takes a photo of it, and then the films are stolen, and only the story remains in the person’s hands. That is, we are in front of this space of Babyn Yar simply with its history and with scattered memories.

Then, in 2012, I had a feeling that I needed to return to the monument to Volodymyr Melnychenko and Ada Rybachuk, to some aspects of that competition, and perform something ritual in Babyn Yar. It seems to me that the biggest problem of what has been happening in the last three years is the attempt to find a total language. It is about the power over space and the power over the shared memory.

I remember the terrible scandals surrounding the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in central Berlin. It is even difficult to call it a monument — it is a large object. And if a person gets inside, it is almost a physical experience of death.

The objects in Babyn Yar now function as in Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Solaris when the areas of memory appear in this impossible, incomprehensible ocean. If we consider these objects as flashes of consciousness, flashes of attempts to talk about it, such points, it is even not bad.

Once I had an idea: to make the most splendid botanical garden in the world in Babyn Yar and try to call the plants by the names of the people. Perhaps, one of the horrors of catastrophe is that we can neither accept nor tell the stories of 6 million people or the stories of the repressed. The tragedy is also in the difficulties of talking about it every time and living with it every day. Everyone has the right not to notice it. There should be no violence against future generations to force them to be stuck in the worst of our stories. As soon as we say that we know what to do with it, we claim power. We will come now, we will arrange such a memory for you! This is a critical issue because the scale of this murder in primordial violence is incomprehensible. And we cannot pursue it without knowledge, humility, and awareness of our smallness.

Many years before the book, I wrote an article, “The Walk in Babyn Yar.” I strolled and described the monuments, and eventually, the first text in this book section grew out of it. It was an incredible day. I think that if a person enters this space, just gives themselves to it and lives through it — the unbelievable happens.

I walked from monument to monument, looking at men drinking beer while someone playing football. Then I went upstairs and saw that the mourning wreaths were “growing” on the trees. I have photos, I did not invent anything. Literature also presents this problem — a feeling that you do not invent anything, the world is just arranged in this way. There were graves, then people in cars, the remains of cemeteries with a TV tower hanging above it all, also built on the old cemetery site. And then I entered the forest part — it is stunning there.

It was autumn, in early October, everything around was in gold. I wanted to go to St. Cyril’s Church and got lost. It was a moment of the specific sensation: finally, here I am because previously, it was a total loss of orientation. Suddenly, I heard the metal clanging and saw beautiful children aged 17-20, dressed in The Lord of the Rings costumes. I asked how to get to St. Cyril’s Church, and they told me, “An angel will guide you.” The angel jumped out of a branch, turned out to be a young man, who led me to the church. This is a real story. I do not really know what to do with this place, but, in fact, no one asks me.

Oksana Dovgopolova: But now you do not want the best botanical garden with people’s names?

Katja Petrowskaja: I do not know, I do not know.

The only form of my treatment of this subject was a book, it is my personal ritual. I did it, and I do not make much sense in any other endeavors.

I want to show a photo. We see Liuteranska Street, a woman crossing the road, the theatrical pedestal that my father still remembers — he lived in this house on the corner of Merinhovska and Liuteranska. It was also part of my route to or around my school. This is a spectacular street. That is what happens to a person when they realize that their great-grandmother was killed on the street they used to go to school. And they will discover it much later. Or that the house in which they were born was a German headquarters? It is all about personal space. I do not know if people need it.

When a person lives in a certain place, it is a question of their hearing the space out. It is not about memory, it is about perception. I was once very surprised by Bruegel’s The Fall of Icarus. You see a peasant plowing the land, the sun sets or rises in the distance, a ship. In the bushes, if you look closely, lies a corpse. If you look at the picture for a long time, you can see the feet of a man who fell into the water — it is about a thousandth part of the canvas. Truly, it is a question of how much of the tragedy daily life contains and how much of daily life is contained in the tragedy.

Oksana Dovgopolova: Before we wrap up, we have questions from our viewers. “Katja, please, tell me what you learned about yourself and the space of your memory in the process of writing the book? Or, in general terms, about how memory works in an interpersonal context?”

Katja Petrowskaja: Great question. I just do not know how to answer it.

It is a bizarre process, an endless journey. I am so glad I wrote this book. I had many helpers and many people who were convinced that this should be done. I am delighted that it exists, at least, because I have formulated something about my parents and about people of this type of life. In fact, I wanted to write a book about the 1950-60s and the people around David. Turned out, the tragedies are the strongest, and they are mesmerizing.

And, of course, this is a book about Kyiv, a city of interminable plots for me. Memory, in contrast, is always ahead. We think there is a room, you need to enter it, everything is on the shelves there, you need to turn on the lights and look at the objects. I always fight not for memory but for perception. This is living through some spaces with ourselves utterly, not discerning separate entities. So it seems to me that memory is always ahead.