The House of Alevtina Kakhidze’s Mother: The Monument to All Who Did Not Partake in the War but Became Its Participant

Alevtina Kakhidze created a monument to her mother, which bears a dedication to all civilians who live and die today in the East of Ukraine. But foremostly, this project is a poignant and beautiful expression that intermixes personal and collective memory with reverence for the human. We asked the artist to talk about this tender yet potent gesture.

Text: Past / Future / Art

— This woman, did she fight? At such an old age? Was she in the military?

— No, she was not in the military. The war was going on around her, and that is why we believe that she was a participant in the warfare.

There are people who are caught up in the war. They try to resist it in feasible ways: fostering humanity and securing the space of freed exchange. One may resume that the efforts are in vain. Or indict for naivety and weakness. Or honour the human right to stand for their world, even if it is confusing.

In Ukraine, the war has been lasting for almost eight years, slaughtering thousands. The reality of the dozens is intrinsic to the war — they live and die within it. You do not have to be a soldier to partake in military operations and to be worthy of commemoration.

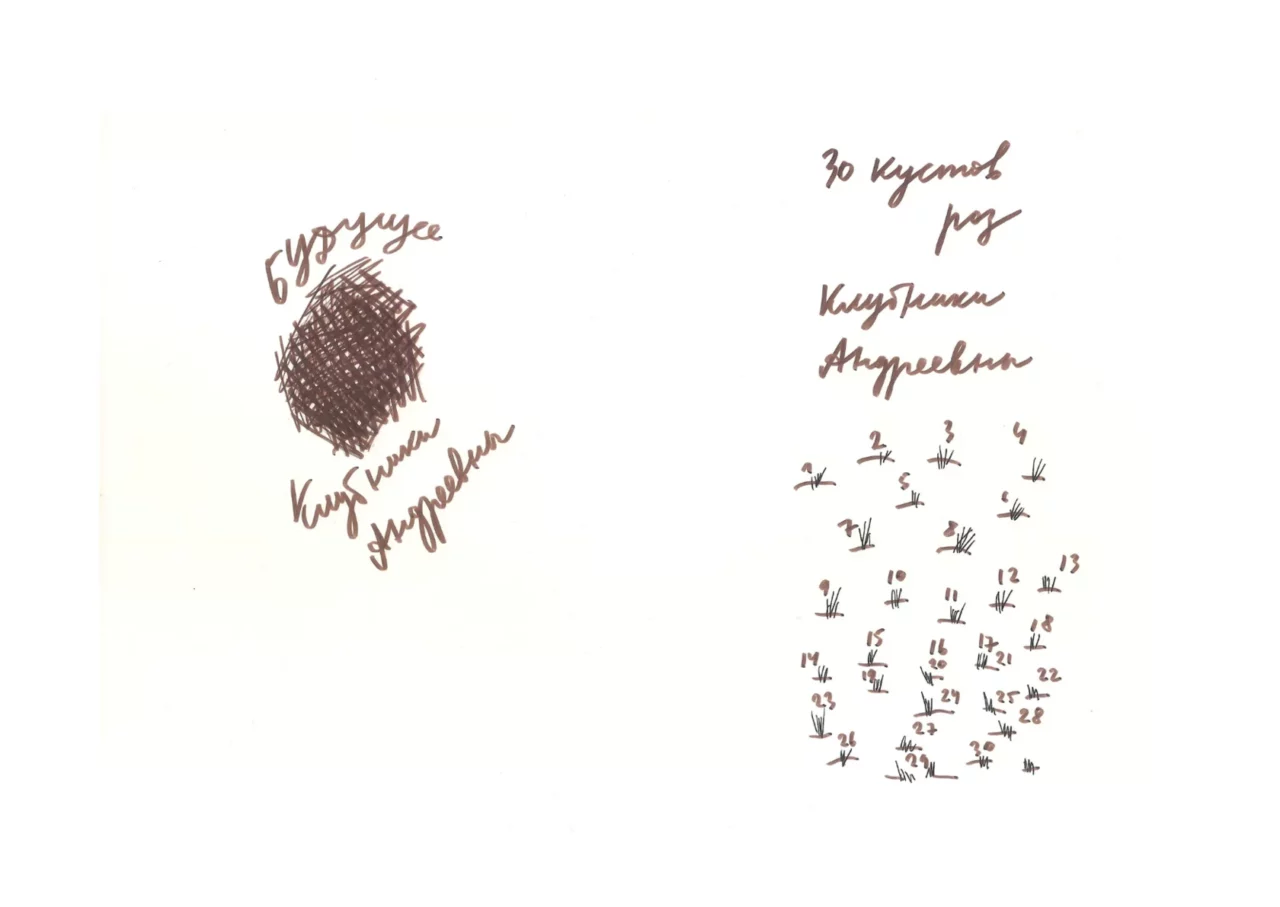

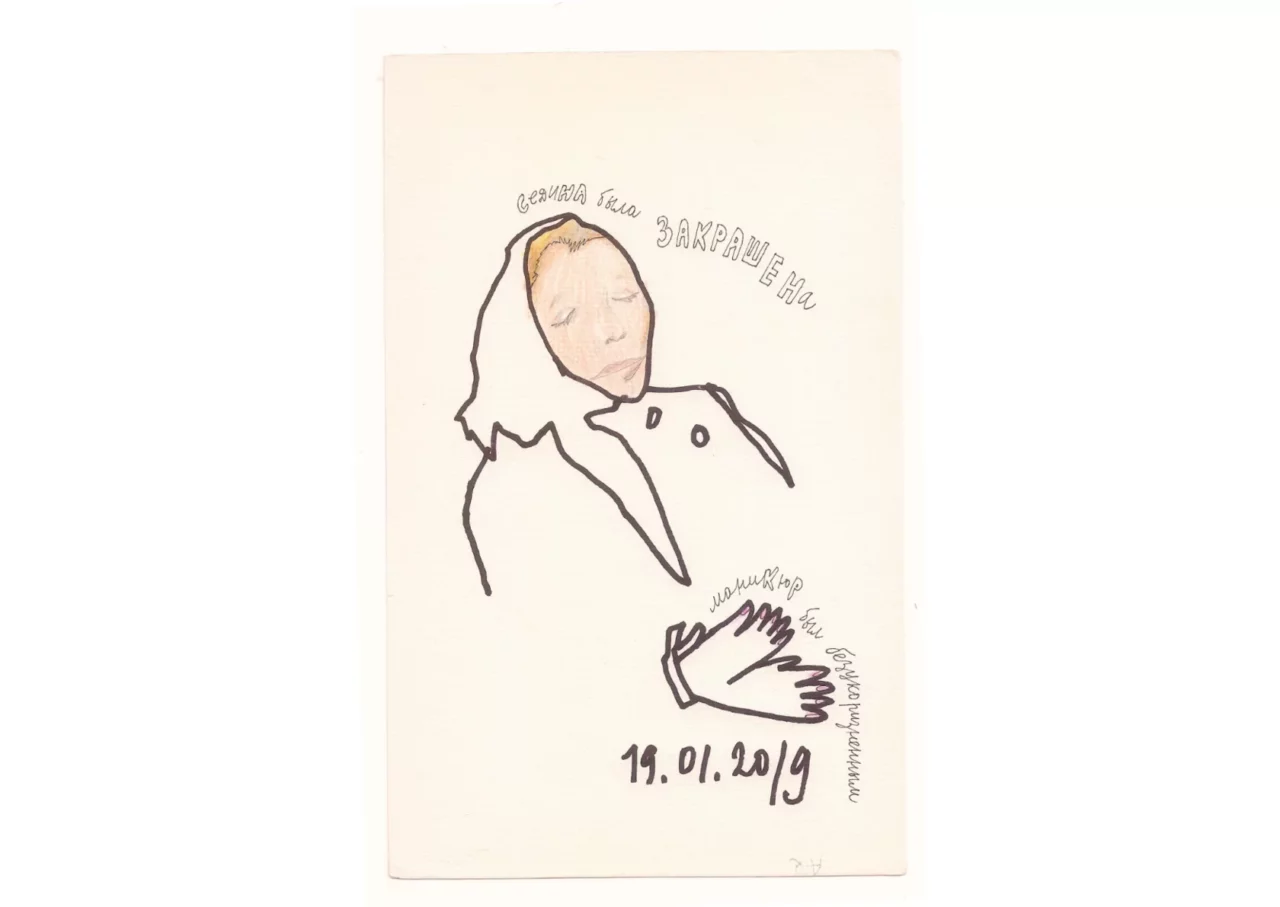

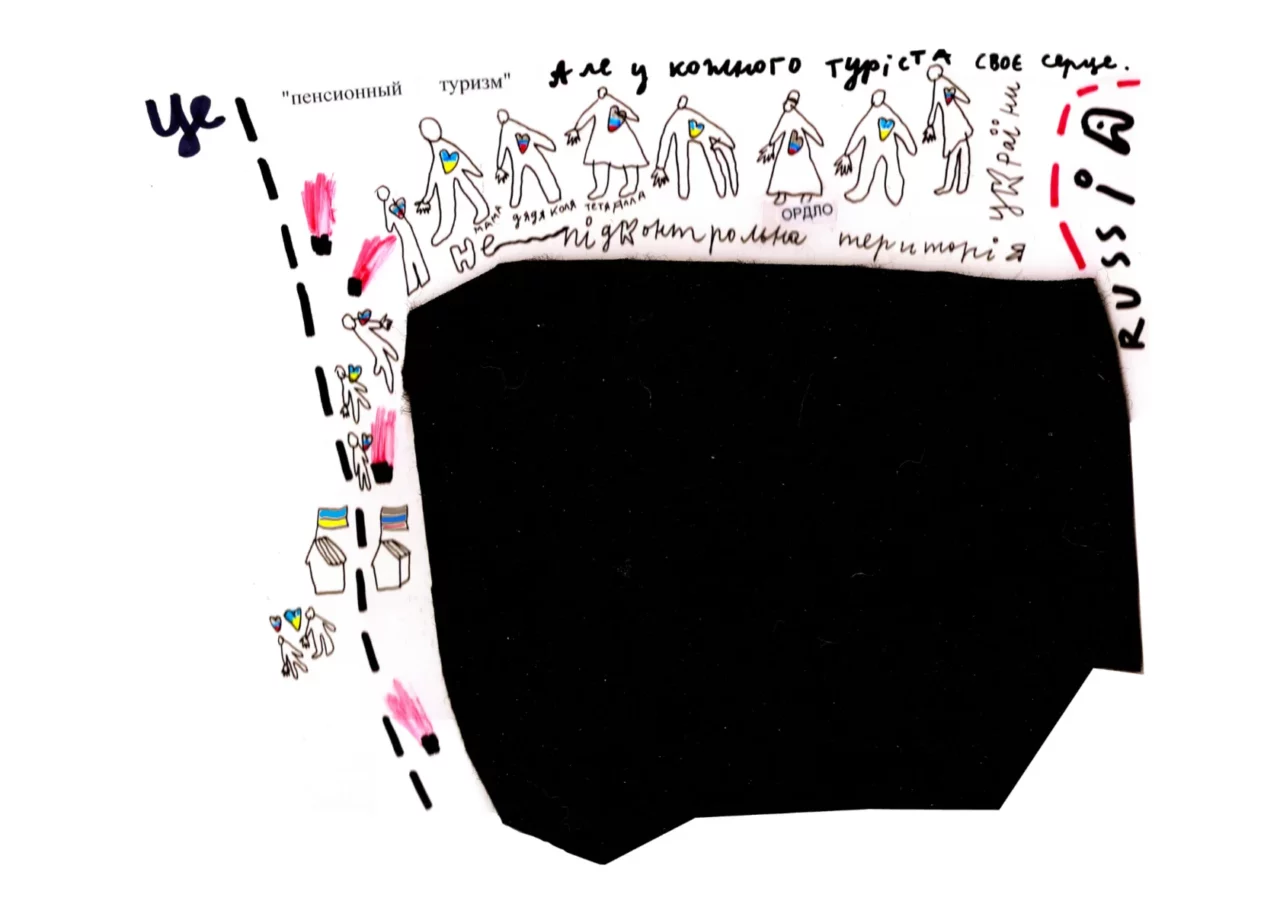

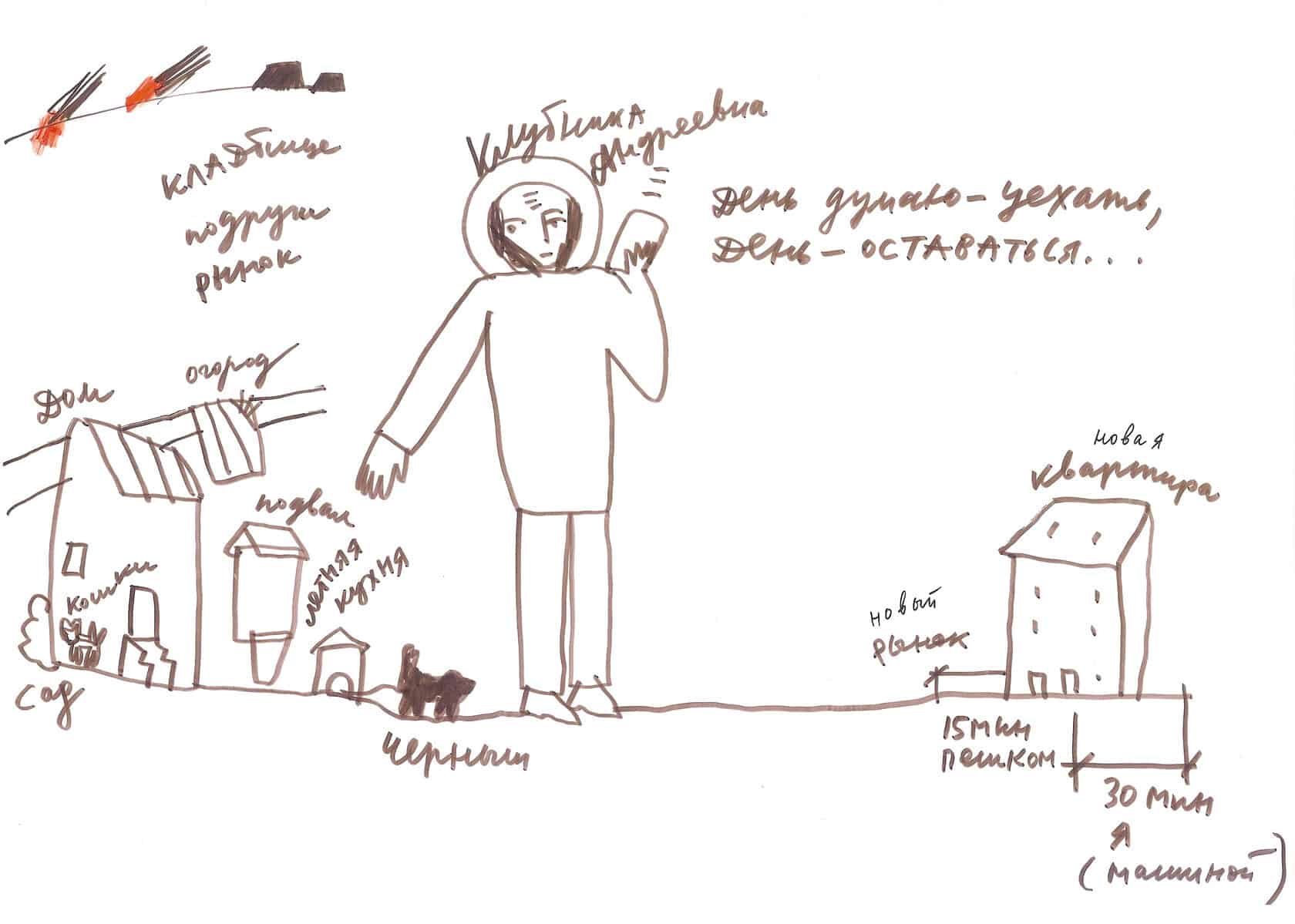

For years and years, Ukrainian artist Alevtina Kakhidze narrated her mother’s life through art projects, namely in the famous series of drawings about Klubnika Andriivna. The mother stayed in the area of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic, and Alevtina had to defend the dignity of the people who, for various reasons, did not flee. And to rebut numerous accusations — “Why do not you take your mother with you?” “My mother is not a sideboard,” answers the artist. “She has the right to her own decision. It does not matter if it pains me to get through it.”

Alevtina Kakhidze, The project Klubnika Andriivna, 2014–2019

2019 brought the irremediable: the artist’s mother suddenly died in line at the checkpoint, at “zero.” She did not go to visit her sister or daughter; she went to “check in.” The latter is one of the terms associated with the phenomenon of “retirement tourism,” which Kakhidze introduced into the artistic space through her drawings. The artist’s mother had the opportunity to relocate away from the difficulties of the occupied territories because Alevtina and her husband purchased a one-room apartment in the Kyiv region for her. But she was ambiguous about the move, and the premortem drawings captured the ambivalence.

“They say that the monument should be unveiled in a year. When your mother dies, you immediately turn into an ordinary person falling under the ordinary rules. I realised that I would not be able to go to the funeral bureau. I needed inner readiness to create my monument. I knew it would be a serious project, but I was nervous about doing something sentimental. This often happens when you lack the distance. And an artist is always a distance. It grants the reflection, without which it is impossible to do something,” says Alevtina.

I NEEDED INNER READINESS TO CREATE MY MONUMENT. I WAS NERVOUS ABOUT DOING SOMETHING SENTIMENTAL

The death of the beloved is always a personal tragedy, but understandable to everyone. The artist shares her thoughts with us: “Mom did not flee, even though she could. She chose her house she built all her life. This was her life, which she did not want to abandon.” Simultaneously, Alevtina ruminates about those people who found themselves on their own in the occupied areas; their homes were left without visitors because their relatives could not reach them: “Many people were forbidden to tend to their beloved who died in solitude on the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republic territories.”

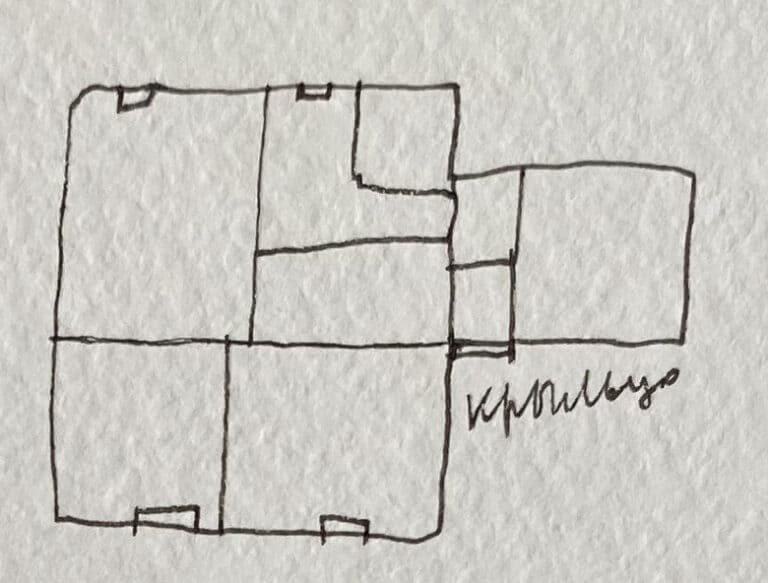

“This house kept a hold on you” was the first phrase the artist uttered, trying to put the memory of the closest person into an image. “I had never asked my mother where she wanted to be buried. It was clear that it should be somewhere near the house. And if it so happened that her body ended up in Muzychi, then the house should be here too. The task was apparent: to relocate the house symbolically,” says Alevtina.

It was a departure point for the artistic search that arrived at the creation of a monument. The monument-reflection on the corporealities of the people who inadvertently become the military conflict participants and whose lives are engraved with the demarcation line.

The artist Stas Turina was a primary interlocutor and a kind of mentor for Alevtina’s endeavour. She had never worked with monuments before, so she had to study a lot, consult, and communicate with others. The artist and sculptor Volodymyr Melnichenko presented Alevtina with a book incorporating the photographs of the monuments he had created for his friends. It strengthened the artist’s faith in the idea. Then it turned out that Stas Turina also had experience in monument construction.

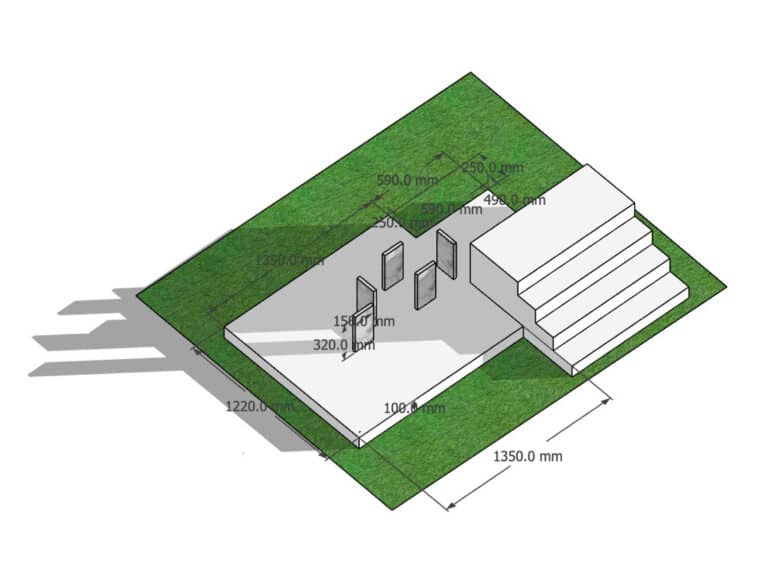

Kakhidze additionally studied the cemeteries — the Lukianivske and the military ones. The architect Olena Orap made many visualisations, assisting in the project’s grounding. The poet Liuba Yakymchuk helped to finalise concise yet essential texts.

“The monument developed into a huge project involving many participants. Such projects are often submitted to competitions and grants. I was not an institution, but merely a single person,” says Alevtina. Nowadays, her artistic search is probably unique. For us, the project that works with memory, it is of the greatest importance — and we want to give a voice to the artist. Alevtina Kakhidze told us how her idea was commenced and developed and who accompanied her in the pursuit of the answers.

THE DOORS AS MEMORANDUMS

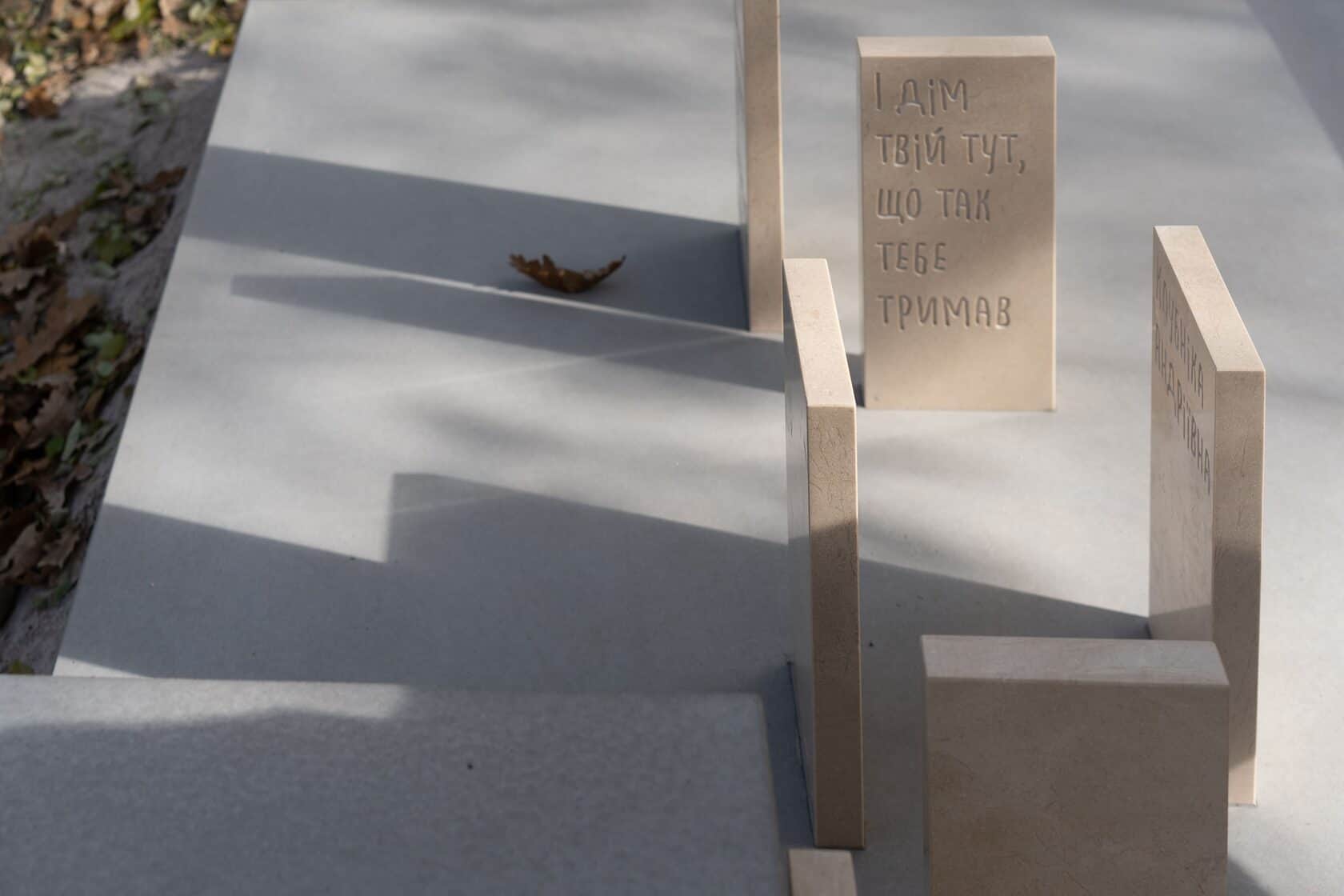

How to relocate the house symbolically? Just to create a model? A house is not merely its walls, bricks, or fence. It is a living space where the points of meanings, the islands of distinct daily dimensions, coincide. Alevtina recalled the house and was even able to get its precise plan. The monument had to embody this particular house, not an abstract idea: “The monument, like our house, has six doors. In the project, they have three memorandums. The first is the most straightforward, every monument features it: the mother’s name, the birth and death dates. This information is inscribed on the front door leading a person from the porch into the house.”

The Monument to the Mother of Alevtina Kakhidze, 2021, Muzychi, the Kyiv region

The photographer — Marho Didichenko

“The four doors in the middle (in the real house, they led from the corridor to the rooms) convey a message written circle-wise: ‘Klubnika Andriivna, you died at ‘zero,’ now you are here, and your house is here, the one that kept a hold on you,’” says Alevtina. “I allow myself to mention the name of Klubnika Andriivna because it is so important for many. I wanted to expand the appeal — not merely to my mother and her experience but also to other people. The third, final memorandum is: “To all who died alone in the russian occupation.”

The memorandums cannot be read simultaneously from a single point of view; you need to walk around the monument. When you look at one door, the inscriptions on the others are not visible. It is like a Japanese garden: the planes do not intersect, and the texts lack polyphony.

The doors with memorandums contour the spaces of the house. Looking at their configuration, we realise where the walls should be. The dwelling’s outline is reduced several times, but the proportions are accurate. Nonetheless, one of the elements had to be presented on a real scale. It is the porch.

“I had an idea to include a place for sitting. So I could come and sit with my mom. Whenever you go to the cemetery, it is always a quiet dialogue,” says Alevtina. The artist was looking for a form for this place, and at some point, she realised that the most natural thing in the house is to sit on the porch: “There, I often waited for my mother when I came home while she was at the neighbour’s house. That is, it is also a site of waiting and tranquillity, the anticipation of mom’s forthcoming return.”

From the old family photo depicting the brothers near the house, the artist and her husband calculated that the porch steps differed in height and width — “that’s how mom made them herself.” It is with uneven steps that the porch is reproduced in the monument. The only difference is their width. For Alevtina, it was important that people do not step on the “house”: “The length of the porch is real, but the width of the stairs is not, the foot does not fit. I really did not want it to fit. The stairs grant a porch feeling, where you can sit from the side but not climb. I made its height comfortable to sit — 42 centimetres, the height of regular chairs. But its length is the real length of the small porch in our house.”

MARBLE AND CONCRETE

The monument is made of concrete, a fairly ecological and beautiful material, and the symbolic doors are made of marble. The artist worked with the CONС company, inspired by their concrete works. Alevtina notes that until the very last moment, she concealed the monument’s location because the CONC warned: “Only not at the cemetery.” Later, she revealed her cards: “This is a sculpture, this is my art, but it is at the cemetery.”

Questions arose at every step, for example, which font to employ for the inscriptions. In the artworks, Alevtina always writes texts by hand, but in this case, her conventional writing was incongruous. For about a month, the artist created her own font, departing from the idea that it should “weep” as if water dropped on the letters. Liubov Yakymchuk advised Alevtina to use big letters only for the mother’s name and life dates. Smaller letters had to be developed for everything else so that the memorandums would not “yell.”

When Alevtina was looking for specialists who would do milling on the marble, she sent them the monument model with the texts on the plates. She was always offered a discount precisely because of the content. The man who eventually participated in the assembly disclosed that he cried when he saw the monument. He could not move his family from the occupied areas to Kyiv precisely because of their attachment to their home. “For me, art is genuine when it tackles the social,” the man added.

THE LUMINOUS MEMORY SITE

“Mourning has to be framed in beauty because it grants strength to endure all of it,” says Alevtina. “A friend wrote to me about this work: ‘The luminous memory site.’ It seems like a simple description, not intricate… But it is indeed the beauty that provides a resource to look at a horrendous story and discover something in it for the future. To think about all the people who remain there. Eventually, the most important thing is that with this monument I recognise my mother’s right not to leave, but to stay at her home. Moving the house to the cemetery is a confirmation that I respected her position, her views, and a genuine valorisation of this house. Hence, it should be valuable for me to keep it that way”

WITH THIS MONUMENT I RECOGNISE MY MOTHER’S RIGHT NOT TO LEAVE, BUT TO STAY AT HER HOME

“My memory is finite, but the outline will remain even when I am gone, and someone else can continue the house in their recollections. The artist also has such a task — to archive; it is a specific historical, anthropological role. This is the respect for the life of the deceased, a testimony of memory gesture,” Alevtina concludes. Beauty, not vengeance, will give us the strength to endure pain and overcome what tears us apart. When we mourn a loved one, we do not resort to generalisations and abstract figures, to something superhuman and epic, in the rays of which a person vanishes. “What is memory? Recognising a person as they were, not as you wanted to see them,” states the artist.

The photographer — Marho Didichenko

To keep in memory a person with their choices and vulnerability is a critical commemoration gesture in a world torn by conflict. Retaining the ability to see faces in “social groups” and “typical representatives” is the only thing that will help us preserve our humanity. By mourning a specific person and their fate, we can own the dedication made by Alevtina Kahidze: “To all who died alone in the russian occupation.”

TO ALL WAR PARTICIPANTS

During the monument installation at the cemetery, people who were painting the fence nearby asked: “This woman, did she fight? At such an old age? Was she in the military? “No,” answered Alevtina, “she was not in the military. The war was going on around her, and that is why we believe that she was a participant in the warfare.” Naturally, when people think about the death of warfare participants, they first suppose the military. But there are other participants. “Perhaps, this is the first monument in Ukraine dedicated to the people who did not partake in the war but are its participants,” the artist suggests.

The Project Team

Alevtina Kakhidze — concept, font, management, engineering solutions

Stanislav Turina — mentoring

Olena Orap — architecture

Liubov Yakymchuk — editing

CONC firm — concrete, installation

Bareks Marmur, DECORart — marble, miling

The cover photo: The Monument to the Mother of Alevtina Kakhidze, 2021, Muzychi, the Kyiv region

The photographer — Marho Didichenko

The images provided by courtesy of Alevtina Kakhidze