LENINOPAD AND THE JOURNEY OF ENGELS FROM POLTAVA TO MANCHESTER

On July 22, an online conversation “Soviet, empty, yellow-blue” took place as part of the Past / Future / Artproject. Yevgen Nikiforov showed unique images from his photo series “On Republic’s Monuments” and, using them as an example, told us what is happening to the public space of Ukrainian cities. In the first of the two publications, we share the photographer’s most interesting thoughts. Read the second part of the conversation by following this link.

Since 2014 I have been working on the project “On Republic’s Monuments”: studying and documenting monumental art and the changes to the public spaces that result from the decommunisation law. In the last seven years, I have visited about 600 geographical localities, so I will tell you what I have seen during these expeditions in Ukraine.

This project began with the demolition of the first Lenin in Kyiv at the start of the so-called Leninopad (Leninopad or Leninfall refers to the process of demolition of monuments to Vladimir Lenin in Ukraine — note by Past / Future / Art ) on December 8, 2013.

This and other photos by Yevgen Nikiforov, from the series “On Republic’s Monuments”, 2014–2020

I started documenting what was going on. The demolition was chaotic, it occurred during the Maidan period, and the police tried to stop the process, but it did not succeed in Kyiv or in hundreds of other cities. So I began to document what I believe will disappear in the years to come. The decommunisation law had not yet been signed and announced.

I WATCHED THE POPULATION’S CHAOTIC ATTEMPTS TO CHANGE SPACE WITH THEIR HANDS, TO GET RID OF THE PAST OR TO SHOW THE VECTOR OF THE FUTURE

At first, I photographed how everyone started to paint things in yellow and blue. Public utility companies set the trend — they started repainting massive objects like carousels, street crossings, fences around building sites and in the downtown, landfills, etc.

Following the trend, volunteers began to appear, collecting money for paint and repainting everything that the public services had not reached — for example, the old fence on Shevchenko Boulevard. Such people with boxes “For Paint” stood at crossroads, at traffic lights and collected money. We don’t know whether they collected funds for the paint or it was just a way of earning money.

It was a way to legitimise the building insulation. You couldn’t argue with the man who did it because his gesture was patriotic. It was also a way to legitimise the insulation on the site of the mosaics that used to decorate buildings — you sort of doing good, make the house more comfortable, and destroy the monumental work. But in this period, just after Maidan, no one would probably have asked you why a particular work of art was hidden or destroyed.

These are some of the ways the utility service providers operated in cities. You can see diversity and ingenuity, but most of the time, it’s inappropriate — for example, tree stumps painted with yellow and blue paint. These trends have also reached the resort area. There, retail outlets began to change their colour scheme, possibly creating a competitive advantage over others.

Also, yellow and blue started to become ideological symbols. In Sumy, for example, there was a slogan and a portrait of Lenin. Or a fence on which stars symbolising the movement towards the European Union were drawn.

By using paint, people also try to preserve something from being destroyed. They started to protect monuments that were valuable to them because not everywhere people supported Leninopad. During the chaotic Leninopad of 2014-2015, all the main Lenins were demolished, except the one in Zaporizhzhia. In some cities, they stayed there for a long time, until 2017. For example, in Lysychansk, Lenin stood painted for a long time; in Sloviansk, it was simply covered with blue-yellow paint.

Even before the decommunisation law was passed, I knew that monuments would be destroyed. However, questions still arise: which monuments and names fall under the decommunisation and which do not. So I started to focus on the destruction of monuments. I wondered how they would disappear, what would appear in their places, where they would disappear.

The name of the project “On Republic’s Monuments” refers to the “Decree on the Monuments of the Republic” of 1918, a document of the newly established Soviet power. It says that the monuments erected in honour of the kings and their servants must be demolished. Instead, artistic councils must propose new heroes, and new monuments must be raised in place of the old ones, which would proclaim revolution and feats of the Soviet people.

WHAT TOOK PLACE BETWEEN 2014 AND 2015 REMINDED ME OF A CENTURY AGO WHEN BELLS WERE MELTED DOWN, AND NEW MONUMENTS APPEARED

I started hunting for monuments that I thought might disappear. I often returned to the same location several times, sometimes for the fourth and fifth time.

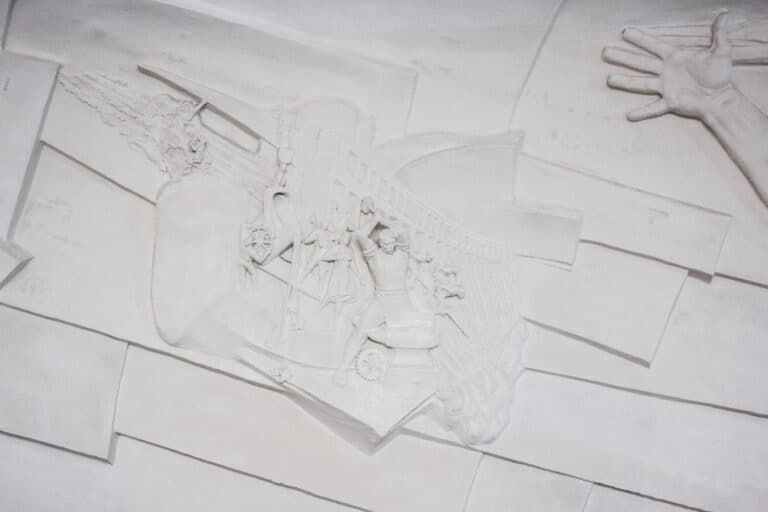

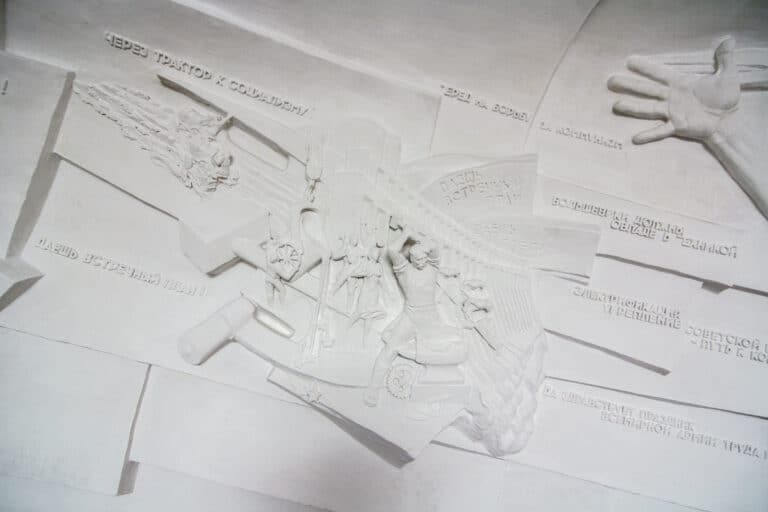

This is my favourite example of how decommunisation works only partially and covers historical facts with white spots. For example, at the Teatralna metro station in Kyiv, there is a giant frieze of bas-reliefs at the top station. I photographed it in 2015, and a year later, inscriptions, slogans, or certain characters in this picture were partially hidden. All that remained was what the metro workers considered legitimate.

In fact, a wave of decommunisation in the Kyiv Metro took place in 2015. The forbidden symbols were simply hidden. It’s still there, but it’s covered with metal panels.

Lenin in Zaporizhzhya was the last surviving in the whole region; it remained untouched till 2016. The locals defended him for quite a long time, dressed him in the uniform of the national football team, in a vyshyvanka (Ukrainian embroidered shirt). Underneath this Lenin, there were sculptures of workers, and in theory, they were not supposed to be decommunised as there’s nothing about such cases in the law.

I came to Zaporizhzhia on the day when the demolition of Lenin was planned, but I had to stay for three days — there were always people who stopped the process, the communal services did not give the exact date and time of the beginning of the demolition. Eventually, I had to leave. When the demolition finally took place, this pedestal was covered with a Cossack and many flags.

I constantly see the news that yet another “last” monument to Lenin was discovered. It seems to be that this will be an almost neverending story because there are many small villages with no civilization and no photographers. For example, one such Lenin still stands in a small village in Kherson Oblast. And I’ll be interested in going back to this village in a few years and seeing if this Lenin was discovered.

One way to preserve a monument in public space is to partially obscure facial features. For example, the monument to Marx in Hotyn is now without a moustache and eyebrows.

There are also some controversial monuments about which the law says nothing or is not clear, such as the sculpture by Mykola Lysenko in Mykolaiv. Their fate is unknown: whether they go further into the sculpture park, stay where they are or are decommunised in other ways.

The monument to Nikolay Shchors is one of the few that has not yet been decommunised. It should happen according to the instructions of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance.

The whole time I’m working on this project, I take a control shot of this place every year. For example, in 2016, only the lower part of Shchors’ pedestal was damaged, and in 2017, activists attempted to demolish it by themselves, but thanks to the police and local authorities, the monument has been preserved. It was later covered with yellow and blue fabric and scaffolds. Then at night, someone cut off the horse’s leg, and I climbed on these scaffolds, too, to take some photos.

The monument is still in place, and I’m wondering how it will change over time. Some activist artists made a new leg for the horse. The flag began getting worse; then it was updated, then it disappeared.

Another favourite monument of mine is a monument to the soldiers of the 1st Cavalry Army, which stood above the Kyiv-Chop highway near the village of Olesko, Lviv region. After the road was repaired, the track slightly changed the location, and the monument was left behind, and locals began cutting off pieces of copper the monument was made of. By 2015, this was considered vandalism, but with the decommunisation law, what was illegal became legal, and the process of cutting copper accelerated. I photographed it in 2016, and a few months later, there was only a frame left of the monument. Now it’s hard even to find where it was.

Once I helped a British artist, Phil Collins, find a monument to Engels — he planned an artistic action to move the pedestal to Manchester. Engels was an outstanding figure for the city because he defended the working class, but there was no monument dedicated to him there for a long time. The moving of the monument was specifically for the Manchester International Festival (MIF).

I found one Engels in the Poltava region. Locals hid it behind the shop, said it was the most beautiful thing in the village and would stand here until the regime changes. The monument, which nevertheless went to Manchester, was found in the tiny village of Mala Pereshchepyna in the same Poltava region. It was divided into two parts and stored on the grounds of an oil mill. Phil Collins liked the monument, and within a year, moved it to Manchester. The BBC made a film about this trip. Engels was set almost in the city centre, people celebrated this event, performing the song “Communism’s Coming Home”.

LOCALS HID ENGELS BEHIND THE SHOP, SAID IT WAS THE MOST BEAUTIFUL THING IN THE VILLAGE AND WOULD STAND HERE UNTIL THE REGIME CHANGES

A separate category is monuments to pioneers, which are repainted in yellow-blue or “dressed up” in the form of youth organisation Plast. And these monuments are preserved.

And now, let’s talk about how we can preserve monuments in a civilised manner. The fate of Lenin, who used to stand in Komsomol Park in Odesa, is exciting. At first, it was on Kulykove Pole, but then it was moved to the park, where I photographed it — there, someone threw paint on it. A year later, he was transferred to the Frumusica-Nova village, where a park with dozens of fallen monuments was created. It’s actually an eco-settlement, which also preserves monuments.

There is also conservation in museums. For example, in the Mariupol museum, there are monuments to workers, Lenin, Zhdanov. Another example is the Recycled Materials Museum in Kyiv.

Another private initiative exists in Kharkiv. The owner collects pedestals in the courtyard in front of the entrance to the building of the glass-cutting workshop.

There are private museums I haven’t been able to get into yet. For example, in Kherson, there is a museum of totalitarianism in a private house, where you can come by appointment. There are also monuments in the forest in the Sumy Region. It may become a sculpture park.

A private initiative of a smaller scale: on Nyvky in Kyiv a few years ago, I managed to find the owner, who keeps sculptures — which his friends bring him, or he buys himself — near his fence.

As for the official museum of totalitarianism, it has been promised since 2016. Plans for such a park were announced, and the location on the territory of the former Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy of Ukrainian SSR was shown, but nothing happened.